New Yorkers are awakening to the disaster they dodged when Albany legislators made sure their surcharge on for-hire vehicles wasn’t sullied by a cordon toll on private cars and trucks.

We’re just finding out that collecting the congestion toll would have required a “massive new bureaucracy” to process data from “massive and costly camera systems.” What’s more, this “electronic version of a Trump-style ‘wall’ around Manhattan” would have been “out of date by the time it [was] built.”

Nah, just kidding. That hit job was courtesy of Mitchell Moss, director of NYU’s Rudin Center for Transportation and a member of Governor Cuomo’s Fix NYC panel. The first three quotes are from Moss’s op-ed in the New York Post, where he disregarded common-sense modeling results and pronounced the Albany deal “a major victory for all subway and bus riders.” The other appeared in a March New York Times story, Is Your E-ZPass the Key to Congestion Pricing?

Ah yes, the infernal E-ZPass, so "costly" and "bureaucratic." It will never work in New York.

As the Times reported yesterday in recapping congestion pricing’s slow death in Albany, Cuomo made a half-hearted push for a $200 million budget item to design and install congestion zone infrastructure. That figure was probably just a placeholder, but it matches up well with my itemized cost estimate for a Fix NYC tolling system in the “Cordon” tab of my BTA spreadsheet model. Here's what would go into that system.

First, I count just two dozen Fix NYC tolling locations needing E-ZPass readers and license plate cameras: ten southbound or two-way avenues or highways at 60th Street; the four East River bridge exits into the Manhattan street system; nine FDR Drive exits up to 53rd Street; and one to round up the total. The Fix NYC report didn’t price the cameras or structures, but I budgeted each installation at around $2 million, based on estimates of $395,000 per site from the 2007-2008 congestion pricing plan advanced by the Bloomberg administration, which I adjusted for inflation and quadrupled to allow for tight spaces and NIMBY resistance. The total for all 24 sites: $45 to $50 million.

For system engineering, integration with Port Authority and MTA tolling, environmental impact statements, and the inevitable legal challenges, I budgeted almost $110 million, based on "soft" cost estimates in the Bloomberg plan. In case a new central processing system might be needed, I tacked on another $110 million. The upfront cost for the whole deal — infrastructure, integration, engineering, EIS, legal, CPS — then comes to $265 million.

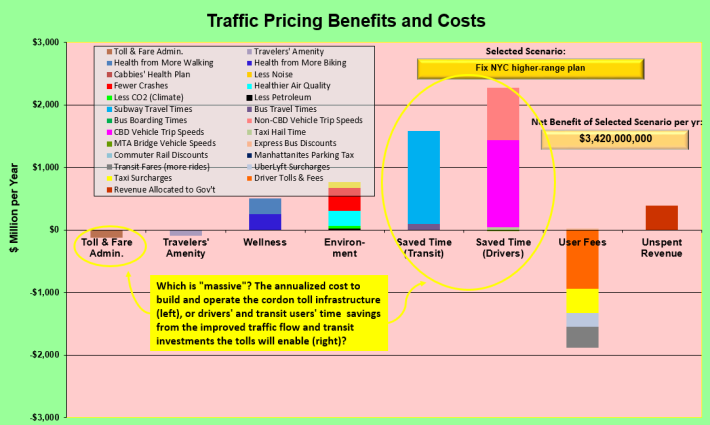

Is that cost “massive,” as Moss alleges? Hardly, considering that the structures and systems would be in place for a decade or more. Nevertheless, I amortize the cost over just five years. That’s $53 million a year, which I count in perpetuity to allow for system maintenance, upkeep and improvement.

What about Moss’s “massive new bureaucracy”? We already have E-ZPass, thank you, not just in and around New York but in 16 states as far west as Illinois, as far south as North Carolina, and as ornery as West Virginia. Yes, it costs something to process each transaction. But those costs are well-established and, like most things digital, aren’t spiraling out of control. In my modeling I adjusted the Bloomberg administration’s 2007 per-transaction costs to a 2018 basis and threw in 50 percent for contingency. I also budgeted for “manual review” of 10 percent of all transactions. Even with all this wiggle room, the transaction costs amount to just $66 million a year. Combined with the $53 million in annualized capital costs, the total cost to build and run the tolling system -- bureaucracy and all -- is $120 million a year.

What’s really massive, then, isn’t that figure but its difference from the nearly $4 billion a year in travel time savings that the tolling system will enable: $2.3 billion for drivers and $100 million for bus passengers from more freely flowing traffic, plus $1.5 billion for subway passengers once the congestion tolls manifest as more reliable and frequent subway service:

I’ll meet Moss partway on his “out-of-date” quibble on cordon tolling. Someday, all vehicles, not just regulated for-hire vehicles, will be able to be tolled by GPS. This will not only obviate the need for physical tolling infrastructure, it will also allow granular and proportionate congestion charging to replace binary cordon tolling. Bruce Schaller’s most recent report, Making Congestion Pricing Work for Traffic and Transit in New York City, does an excellent job summarizing recent progress in GPS tolling, but Schaller is clear that such a system must start as voluntary, “as an option to paying the congestion fee in the traditional way, using E-ZPass.” In other words, we’ll need to walk with cordon tolling before we can run with GPS tolling.

There’s more train-wreck in Moss’s Post op-ed than I can dissect here in full. But I can’t pass on pointing out his logical fallacy that the 20-year drop in vehicle entries to the CBD (which I’ve duly noted for years in the BTA’s “Hub-Bound” tab) means that “tolls on cars entering Midtown Manhattan won’t end congestion.” Au contraire, the persistence -- indeed, the relentless rise -- in traffic gridlock reflected in declining GPS-derived taxi-speed averages points to a greater, not lesser benefit from each and every motor vehicle removed from our streets.

As I pointed out in Streetsblog last week, clearing out street space by surcharging for-hire vehicles without also cordon-charging cars and trucks will only “induce motorists to make more trips on the free bridges and across 60th Street.” Moss, of all people, should be aware of the multiplicity of feedback loops in urban transportation. Whack-a-mole may make for punchy op-eds but it’s no substitute for holistic policy analysis and policy making.