Crossposted from Second Avenue Sagas, where, by the way, Ben Kabak is running a Patreon drive to support his transit watchdog work.

With just under a year to go until the much-heralded L train shutdown, Manhattanites are growing restless. They’re not, however, concerned with the transit apocalypse that may be headed 14th Street’s way, and they don’t seem to believe, as many transit advocates do, that DOT and the MTA’s mitigation plan isn’t robust enough. Rather, with a combination of trumped-up NIMBY-esque concerns over traffic, bike lanes, and bus lanes -- and some last-minute seemingly bad-faith arguments over ADA compliance -- a group of West Village residents has sued DOT, the MTA, and the Federal Transit Administration over the shutdown.

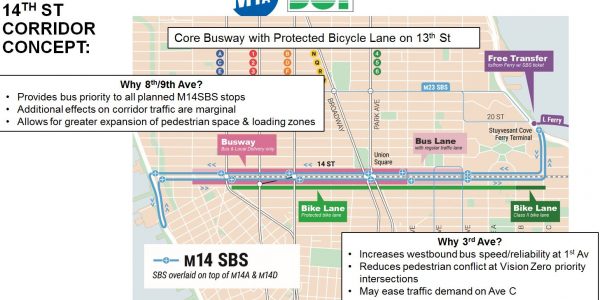

Over the past few months, as DOT and the MTA increased the pace of public presentations regarding the looming 2019 L Train shutdown, it seemed clear that a lawsuit was in the offing. Led by attorney Arthur Schwartz, who has variously put himself out there as a lawyer for a group of block associations, a resident, a homeowner, and even the Democratic district leader for some of the areas affected by the L train shutdown, various residents started making your typical NIMBY noises against the two-way bike lane planned for 13th Street and the temporary busway planned for 14th Street. They raised concerns, not backed by numbers, of increased traffic on side streets and business Armageddon brought on by delivery vehicles being restricted to avenues. It’s been the typical litany of complaints safe streets and bus lane advocates have heard for years, and it seemed practically provincial coming from a wealthy group of self-proclaimed progressives living in the uber-gentrified, transit-rich West Village.

Last week, Schwartz filed his suit. It’s a lengthy complaint that relies on the argument that the various parties are in violation of state and federal environmental review laws. Schwartz alleges that the scope of the planned mitigation -- a shutdown of the tunnel coupled with vehicles restrictions, pedestrianized streets, and a two-way bike lane -- along with its geographic proximity to a landmarked neighborhood requires at least an environmental assessment and perhaps a full Environmental Impact Statement. In light of recent bad press the MTA has received over its alleged flouting of ADA requirements, the plaintiffs tacked on allegations that the shutdown work itself is in violation of the ADA. (The complaint is available here as a PDF if you wish to read it.)

The ADA concerns are seemingly the easiest to address. In fact, the L train mitigation plan includes significant ADA accessibility upgrades with both the First Avenue and Bedford Avenue stations set to become fully accessible with the addition of new elevators and with Union Square set for an escalator to the station mezzanine. (Access to the L at Union Square is already accessible except for the transfer between the L and 4/5/6, but that is a function of the track layout and IRT platform positioning.) No ADA work is scheduled for Sixth Avenue or Third Avenue, but Third Avenue will receive platform edge doors as part of a pilot. The complaint alleges that stairway renovations without accessibility upgrades violate the ADA, but even amidst what many feel are rampant MTA ADA violations, that is a tenuous argument at best, and one made in bad faith to stack claims at worst. Refurbishing stairways by itself isn’t generally enough to trigger an ADA violation.

The meat of the complaint revolves around the contention, as I mentioned, that DOT and the MTA are in violation of local and federal environmental review laws and additionally that the FTA is in violation of federal law if it has not required the proper environmental assessments. Here, the suit strays onto slightly firmer ground, but only slightly and only very narrowly. The bike lanes are easy; they are specifically exempted from federal environmental review requirements. In subsequent comments, Schwartz tried to claim the bike lane is one piece in an overall mitigation plan, the totality of which is subject to environmental review requirements, but the complaint on its face makes no such allegation. (Considering how easy it is to dismiss the complaint over the bike lane, you would think Schwartz would be careful here, but he fell back on the tired anti-bike trope of calling the pro-bike planners at NYC DOT "zealots” during his comments earlier this week. Been there, done that.)

So the key legal question is a narrow one: Is a prohibition on most vehicles in favor of a bus lane on a non-24/7 basis that is designed to be a part of a comprehensive mitigation plan for a temporary shutdown of the L train subject to environmental review laws? The FTA’s website on the topic provides some guidance but no definitive answer. DOT and the MTA’s planned bus way is a reallocation of existing space and not what the FTA generally considers to be new construction. Furthermore, the FTA itself has indicated that an EA or an EIS isn’t required, and courts often give significant leeway to agencies in interpreting their own regulations.

Schwartz’s complaint restates significant portions of the city, state, and federal laws at play, and he details the dialogue to date over the shutdown plans. He doesn’t convincingly argue why the FTA doesn’t deserve deference or why the temporary non-24/7 bus lane requires these environmental assessments. Instead, the complaint draws conclusions -- “closing 14th Street to vehicular traffic will cause horrific traffic jams” on nearby side streets -- that likely wouldn’t stand up to scrutiny in litigation, but it’s not clear DOT and the MTA can win on an outright motion to dismiss. Even though we know the busway is a watered-down plan, and even though we all know a mitigation plan that doesn’t further limit vehicular access to the affected area will be far far worse for Schwartz and his plaintiffs, the law may still require some level of environmental review. I’m still working on reaching out to environmental law lawyers I know in the hopes of a more definitive answer.

But legal considerations aren’t the only elements at play here. Schwartz’s law firm is called Advocates for Justice, but it’s not clear whose justice he’s interested in. One element is, as always, who gets to make decisions on streets and transit that impact everyone. Schwartz claims he’s suing on behalf of “residents of Williamsburg and west-central Brooklyn” but none of them are named plaintiffs. They also have the most to lose when the L train is shut down, but as we saw years ago with the demise of the 34th Street transitway, those constituents aren’t often asked to the table in high-stakes legal discussions over a project's fate.

Furthermore, Schwartz’s comments last week betrayed certain prejudices. He claimed that the MTA and DOT should have chosen the longer shutdown options on the table. Completely ignoring the MTA’s concerns that dust from the construction would make train operations through the Canarsie Tunnel unsafe for passengers during a piecemeal shutdown, a five-year plan that knocks out service on nights and weekends would be far more disruptive to a line that sees heavy ridership late at night and during the weekends and is a key conduit for lower income workers who need to commute in off hours. A total shutdown will be bad enough for 15 months, but five years of these disruptions would hurt those who can least afford it (and need transit justice more than the West Village does).

My biggest fear, however, with this lawsuit isn’t its potential success but rather the potential for settlement. To make this go away before the project timeline is in jeopardy, DOT and the MTA could agree to drop certain elements of the plan. The residents made clear they want the bike lane to disappear and want mixed-use traffic on 14th Street. I’m sure either of those would be enough of a carrot to get them to drop the suit, but eliminating any part of a plan that’s already been watered down based on the trumped-up concerns from the very same residents who are now suing would be extremely harmful to hundreds of thousands of transit riders who don’t have the luxury of living in one of Manhattan’s most exclusive ZIP codes.

For its part, DOT says the suit is without merit. The MTA, however, issued a more guarded statement. “We do not comment on pending litigation,” Jon Weinstein, agency spokesman, said to me. “The repairs to the Sandy-damaged Canarsie Tunnel are desperately needed to ensure the tunnel’s structural integrity so we can continue to provide safe and reliable subway service to hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers who depend on the L train every day. We are working with our partners at NYC DOT to craft a thorough and robust mitigation plan.”

Meanwhile, Ben Fried urges the agency and the MTA to fight hard on the transit elements of the plan and perhaps agree to additional ADA upgrades. Despite the protestations from residents that DOT has ignored their concerns, the plans aren’t as robust as transit advocates wanted, and any further movement in response to this lawsuit would set a bad precedent for future transit projects the city should implement. No retreat, baby, no surrender.

As I browsed the case file this weekend, though, pondering how much this whole thing stinks, one filing from Schwartz caught my eye. In a subsequent letter to the court late last week when Schwartz and his clients erroneously believed that planned repaving of 13th St. meant that work on the bike lane was set to begin, Schwartz requested a conference in advance of potentially filing an injunction. The letter is impressively audacious as Schwartz seems to recognize the problems his suit may cause. “There is,” the lawyer writes, “clearly a need for expedited discovery in this case; although the shutdown is planned for April 2019, lengthy litigation, which could lead to a broad injunction and delays, is not in the public interest.” So I pose these questions: Who is in the “public” Schwartz refers to and what are their interests? Exactly what part of this suit is in the public interest after all?