For 40 years, Detroit has struggled to muster the political support to build a coherent regional transit system.

The region came within an inch of finally doing it in 2016, when voters turned down a four-county ballot measure by just 1 percent. A terrible performance in working-class white Macomb County -- a Trump stronghold just northeast of the city -- helped doom the measure.

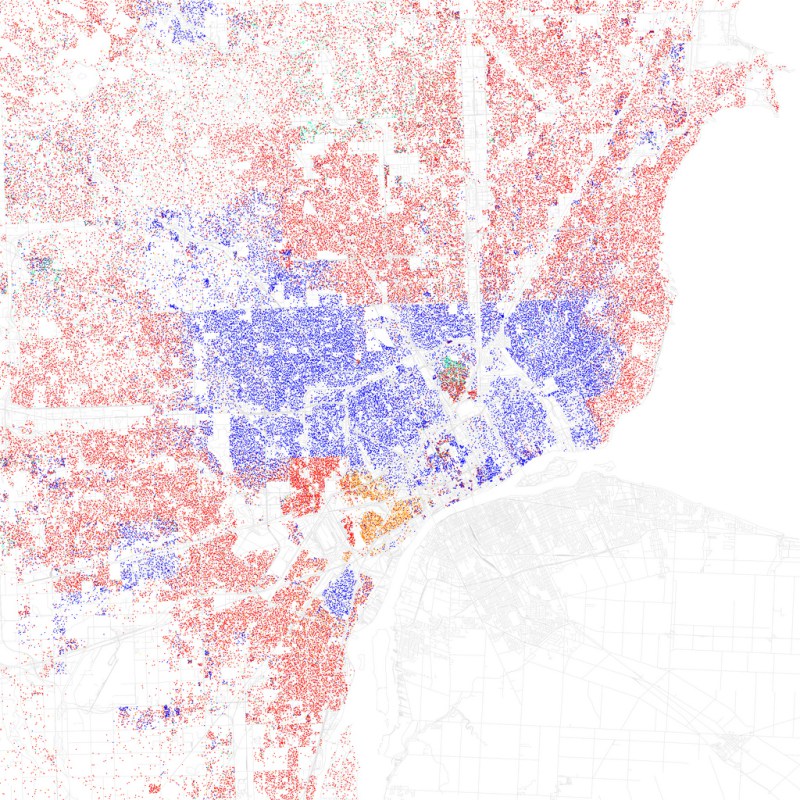

The desire by white suburbanites to maintain geographic segregation has always held back attempts to improve regional transit. While the 2016 ballot measure seemed to signal that the suburbs had turned a corner, polarization is back. Brooks Patterson, the executive of Oakland County, an affluent, largely white suburban area northwest of Detroit, recently said he would not agree to a second go at the ballot.

Patterson got a standing ovation when he broke the news at his annual state of the county speech, saying he doesn't want the suburbs that "opt out" to have to pay for transit.

One of 40 towns within Oakland County that "opted out" of the suburban transit system is Rochester. It gained some infamy a few years ago when they story of James Robertson went viral. Robertson, a Detroit resident, walked 21 miles round trip daily and took multiple bus routes to get to his factory job in Rochester.

Patterson has made a career trading in dog whistles disparaging Detroiters, and in his speech he implied they're out to get things they don't deserve from the hard-working folks of Oakland County:

I will not betray [the opt-out suburbs] and slip some, or all of them, against their will, into a tax machine from which they can expect little or no return on their investment.

Patterson was never a big supporter of regional transit, but he did go along with the 2016 ballot measure. Now, without his cooperation, Oakland County and its nearly 700,000 jobs won't be part of a future ballot measure. That means Detroit's transit system won't be truly regional, and city residents will remain shut off from economic opportunity.

Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan responded to Patterson's speech with disappointment. "Some day, Southeastern Michigan will join the rest of America in recognizing the critical importance of regional transit," he said on Twitter.

Megan Owens, executive director of Transportation Riders United, says it's not clear how Detroit will proceed, but it's possible the regional transit system could continue with just Wayne and Washtenaw counties. Both approved the ballot measure by big margins. Wayne includes Detroit, and Washtenaw includes Ann Arbor.

Better transit connections between those two counties could give Detroit's population -- who are overwhelmingly forced to commute to the suburbs -- access to Ann Arbor's growing tech sector, and the airport as well.

"It's an outrage that [Patterson has] blocked major transit progress for 40 years," said Owens. "It's another example of outdated, parochial thinking that fails to recognize the requirements of a successful modern metro region. Time to stop letting a 79-year old white man who relies on a personal driver dictate public transit for 4 million diverse people!"

If Wayne and Washtenaw counties proceed on their own, Owens thinks it's possible that Oakland and Macomb counties would feel left out and choose to join a few years later. In some regards, Oakland County itself seems to be breaking with Patterson's old-school ways: 46 percent of county voters supported the transit measure in 2016.