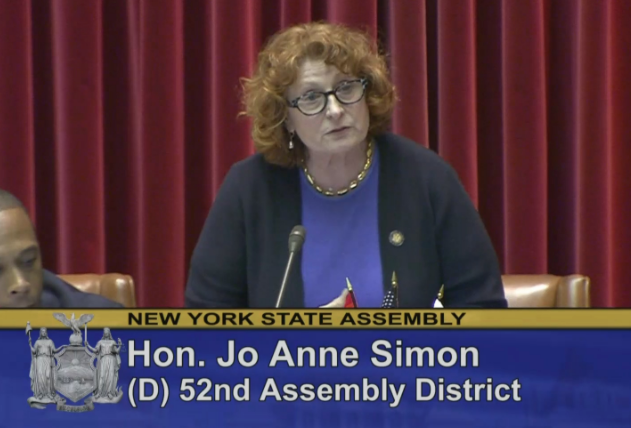

Assembly Member Jo Anne Simon has been on the record in support of congestion pricing since at least her 2009 City Council run. It's easy to see why.

Drivers bound for the free East River bridges choke the streets of Simon's northwest Brooklyn district. In these neighborhoods, only 2 percent of commuters to the Manhattan central business district drive solo, while 93 percent take the subway, according to the Tri-State Transportation Campaign.

Simon won election to the Assembly in 2014, and her presence in Albany is one reason to believe a congestion pricing vote might play out differently this time. Her predecessor, Joan Millman, sat on the fence during the public debate over congestion pricing in 2008 before expressing her support when it was too late to matter.

A long-time advocate for traffic-calming in the neighborhoods surrounding downtown Brooklyn, Simon isn't afraid to go on the record supporting a policy to curb car traffic. Streetsblog caught up with her earlier today to get her take on the Fix NYC panel's congestion pricing recommendations. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Do you support congestion pricing? What’s your take on the FixNYC panel’s congestion pricing proposal?

We need to improve our mass transit and get to a state of good repair, which is a lot more money than congestion pricing will [raise], but we’re not going to get to that by one revenue source. The reality is we need revenue sources that are sustainable. Congestion pricing is one of the best ways that we have to do that. The notion of congestion pricing is just, really, charging more [at] peak hours. You know, everybody accepts the peak and off-peak on the railroads. That, at its very simplest, is congestion pricing.

We can do this. We can do this in more sophisticated ways. The one thing that [Fix NYC] didn’t tackle that the Move New York plan tackled that I think is a critical thing to address is tolling equity. Where we have tolled roads creates traffic in areas like Downtown Brooklyn -- 50 percent of its traffic is through-traffic. A lot of that traffic comes through downtown Brooklyn for one reason: the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel has a toll.

Do you get a sense from your colleagues in Albany that "tolling equity" similar to what was proposed in the Move New York plan would win over skeptics?

I think there are a lot of people that are kind of skittish about the notion of congestion pricing, and I think part of it is we have to do a better job of educating people. The Bloomberg plan was seen as being very Manhattan-centric, and there was kind of nothing in it for the rest of the boroughs, [that] it didn’t really address other boroughs’ concerns. I think both Move New York and Fix NYC recognize that problem, and do a better job of addressing that.

If you look at the commuting patterns of people throughout the city, even in the outer boroughs, the vast majority of them are not driving to the Central Business District regularly. There are people who haven’t driven into Manhattan in 35 years. There are ones that’ll go in once or twice a year for a show, or to pick somebody up, or maybe a couple doctor’s appointments.

There are times where people need to do that more frequently, and there are probably ways that we can address that through programming, right, so that if somebody has to go for chemo every week or something, and they have to drive in because of whatever condition they have, we can find a way of connecting those dots so that there’s some reduced rate, etcetera, etcetera. I think one of the things is that people see the proposed [toll] number, and they react to that.

I don’t think we’re going to get anywhere if we don’t do [congestion pricing]. I think we need to do it. The exact parameters of that, and how it actually works — you know, you can do it well, you can do it not so well. What I hope is that we don’t slice and dice this so that it becomes ineffective.

A few weeks ago, you attended a congestion pricing forum hosted by the Brooklyn Democratic Party in southwest Brooklyn. What was your experience there?

Here’s the concern: People perceive a lack of freedom if they can’t drive over the bridge. The reality is most of them aren’t. The reality is that there is no district where [the percentage of people car commuting] into the Central Business District is two digits.

Does it happen that somebody will need to take a trip into the city? Of course. In my district people drive across the bridge because we can — it’s right there. Will this limit gratuitous driving into Manhattan? Probably.

People have perceptions about what this is and perceptions of how it will affect them without really knowing about it, and they’re concerned. We want to recognize and respect their concerns. It’s an ongoing education process for people to realize that the data is showing that in most districts, half the people or more than half the people don’t even work in Manhattan. People don’t have the same life patterns as they did once upon a time, but in many people’s heads that hasn’t quite adjusted. It’s a process of people learning more, and recognizing we have to make some tough decisions and that the data actually supports the institution of congestion pricing.