The first full week following Mayor de Blasio's reelection began with two incongruous events.

At the Brooklyn Navy Yard on Monday, boosters of the BQX held a press event showing off a prototype of the streetcar that might one day, maybe, ply the Brooklyn-Queens waterfront.

City Hall hasn't had much to say about the streetcar since the Daily News broke the story of an internal memo casting serious doubt on the mayor's claims that the $2.5 billion project would pay for itself via bigger property tax hauls along the route. The Monday presser and a companion event that night, where waterfront developers framed the streetcar as a lure for Amazon, felt like a desperate bid to revive political momentum for the project.

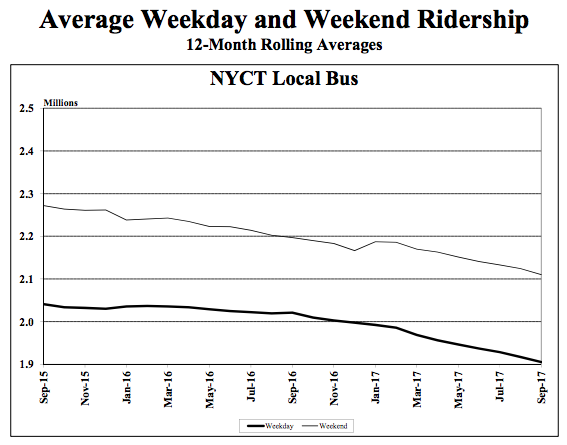

The same day, at a meeting of the MTA Board's transit and bus committee, agency staff presented stunning ridership figures for September [PDF]. Transit use is down across the board, but especially on buses. Average weekday ridership on the MTA's local bus routes declined 6.3 percent compared to the same month last year.

That works out to 157,000 fewer bus trips each day. And it's a big flashing siren alerting public officials to the deteriorating service that several hundred thousand more New Yorkers have to put up with.

De Blasio has limited power to improve the subways -- that's Andrew Cuomo's job. Buses are a different story. Setting aside street space so buses can run without inference from car traffic is the mayor's sphere of influence.

But the mayor hasn't treated slower bus speeds and plummeting bus ridership with the urgency the situation calls for. His DOT recently released a plan for 21 more enhanced bus routes in 10 years. That's not faster than the current rate of implementation, and it leaves much of the work up to future administrations.

City Hall and BQX boosters pitch the project as a sort of parallel transit network that the city can pursue free from the pitfalls of relying on the state-run MTA. The truth is that the BQX is entwined with the subways and buses whether they admit it or not.

For one, the city would need the MTA's cooperation to integrate with its fare system. Without free transfers to connecting MTA service for BQX riders, the streetcar becomes a lot less useful.

More relevant to the current transit crisis are the opportunity costs of the BQX. In addition to city tax revenue that in all likelihood will be needed to prop up the project, a 16-mile streetcar will require huge amounts of planning resources and political capital.

Shedding 157,000 daily bus trips is a five-alarm emergency, and the de Blasio administration's transit resources should be laser-focused on making streets work better for bus riders. That means putting down as many bus lanes on as many routes as possible over the next four years, not waging block-by-block battles to clear traffic and parking off a single streetcar route that might start service in seven years if we're lucky.

New Yorkers will be fine without the BQX. But without a useful bus system, the city's in trouble.