Bill de Blasio got some important things done for streets and transit during his first term in office, but it wasn't enough to keep the city's festering traffic and surface transit problems from getting worse. He'll have to do better in his second term to deliver for his constituents and live up to the political identity he's trying to carve out as a progressive leader.

In the run-up to the 2013 election, there was genuine and justified anxiety that the next mayor would reverse the Bloomberg administration's legacy of pedestrian safety improvements, protected bike infrastructure, and conversion of traffic space into public plazas.

De Blasio dispelled most of these worries pretty quickly by staking out traffic safety as an early policy priority. Under Commissioner Polly Trottenberg, his DOT has made steady progress on major projects like the Queens Boulevard redesign and numerous small-scale fixes like recalibrating traffic signals for safer walking. Thanks to this work, traffic fatalities have continued to fall in NYC, bucking national trends.

NYC DOT also continued to roll out a few big bus priority projects each year, including some, like the bus lanes on Woodhaven Boulevard, where the local politics proved tricky.

On occasion, the mayor himself stepped in to clear political barriers for DOT. The moments when de Blasio conclusively moved forward with safety improvements for Queens Boulevard, East Tremont Avenue, and (after waiting far too long) 111th Street in Corona were the high points for streets policy during his first four years in office.

The thing is, you can count these instances on one hand. De Blasio's transportation priorities, as revealed through his budget, didn't allow DOT to significantly scale up its projects for walking, biking, and transit. This is the most telling aspect of de Blasio's first-term record on transportation.

For all his straining effort to convince national Democrats that he can lead a wave of progressive change around the country, the mayor's signature transportation initiatives did little for New York City's working class. At a time when bus service was slowing down for hundreds of thousands of people, he gave New York ferries for a few and got sidetracked by a streetcar project boosted by waterfront developers. In the run-up to the election, he made a show of cracking down on e-bikes in the city's affluent precincts, the primary effect of which will be to make life more difficult for immigrant delivery workers.

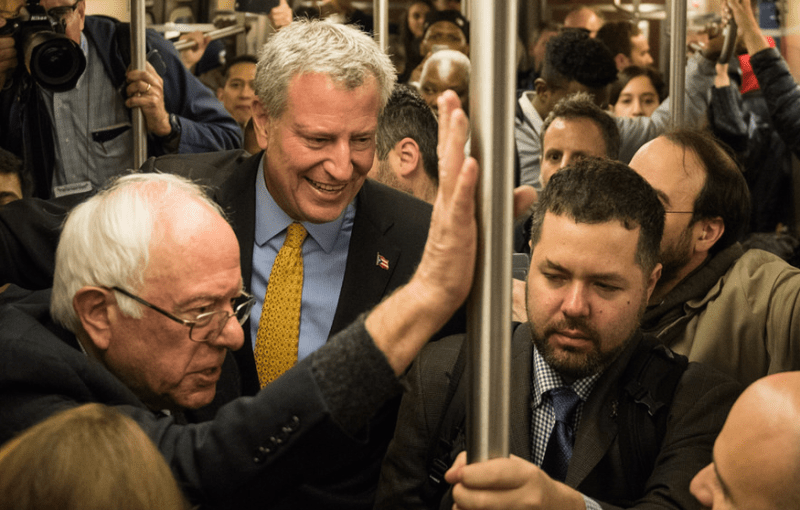

A campaign stop with Bernie Sanders late in October was especially revealing. Here was the mayor of the nation's largest city posing with a Vermont senator at an event ostensibly devoted to improving the subways. The big message was that raising funds through a millionaire's tax will fix the city's ailing transit system. Sanders did his part and endorsed the millionaire's tax while dismissing the rival option of congestion pricing.

By this point, two of de Blasio's own delegates to the MTA board -- Veronica Vanterpool and David Jones -- had very publicly made the case for congestion pricing as progressive transportation policy. The costs would primarily fall on affluent car commuters while working class transit riders would stand to benefit enormously from better service and lower fares.

Standing next to Sanders, the mayor was essentially asking New Yorkers to overlook local expertise and listen to a rural senator instead. But why should New Yorkers care what a man who represents about 600,000 people thinks we should do to improve a transit system that carries nearly 8 million passengers each day? A millionaire's tax does nothing to curb the mounting traffic that is slowing down New York City buses. It's less about policy and more about branding -- a means to burnish de Blasio's credentials with the wing of the national Democratic Party where he desperately craves relevance.

Back in the city de Blasio actually governs, if you look at a map of election results (this one from 2013 will have to do while we wait for yesterday's full returns), it's clear that the mayor takes his base for granted on transit issues. The car-centric districts of eastern Queens, southern Brooklyn, and Staten Island are not where his strength lies.

His runaway margin last night was not a convincing show of enthusiasm -- turnout was too paltry, his approval rating too low, and the path to victory too easy. But it was a frustrating display of how much de Blasio left on the table in his first term. Trouncing a Republican in New York City while Donald Trump is in the White House was a foregone conclusion. The mayor could have delivered more bus lanes, a better bike network, and more car-free public spaces on his way to a certain win.

Heading in to the next four years, the issue of congestion pricing is shaping up as the fulcrum that de Blasio's transportation legacy will hinge on. If Andrew Cuomo does steer a good road pricing plan through Albany -- still a big "if" -- the mayor will be doing his city a historic disservice should he reject it.

New Yorkers are abandoning the bus in alarming numbers in a vicious cycle of rising traffic and slower service. To allow these problems to fester while pretending a millionaire's tax is the solution would let down the very voters who propelled de Blasio to two terms, sacrificing them in a cynical play for a higher national profile.

Congestion pricing is not a panacea that will fix the subways and the buses on its own. But it is a singularly powerful tool to clear excess motor vehicles off New York's congested streets. Combined with a strong commitment to set aside space for buses, bicycling, and walking, de Blasio can use it to accelerate a virtuous circle of efficiency, safety, and fairness in our transportation system.