The Montreal-based app Transit is based on an unorthodox assumption: trip planning limited to directions from Point A to Point B doesn't actually fit the needs of most riders, who travel the same route every day.

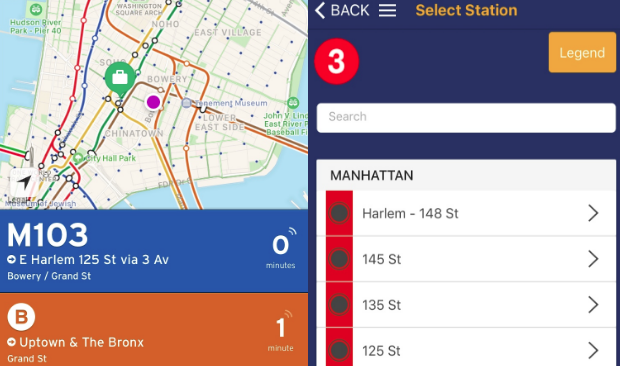

"[The idea] we started with at Transit was to give the information of the next bus at the stop [where they're waiting]," said Léo Frachet, Transit's data lead, at a TransitCenter panel last night. When someone opens the Transit app, they see the transit options arriving soonest in the near vicinity, laid over a map that also includes bike-share stations labelled with the number of bikes available.

Compare that to the MTA's Bus Time and Subway Time apps. While BusTime will suggest nearby routes based on user location, SubwayTime puts users through a process: First you choose a subway line, then you choose a station. If you're close to multiple lines, you have to go through that process multiple times to see what's coming next. MTA Chair Joe Lhota admitted that both apps need to work better for riders when he announced plans on Tuesday to combine them and the Weekender app into a new platform next year.

The last decade has seen a transformation in how transit agencies use data, thanks to the proliferation of smartphones and the advent of open data standards, which allowed third party developers like Transit to create mobile apps. For most riders, phones are now the first place they interact with transit, often before they've arrived at a stop.

"If [the phone] is the portal at which we experience transit first, then this is the way that [agencies] have to make the right first impression with our riders," said TransitCenter's Chris Pangilinan, who moderated the panel, which also featured Ben Kabak of Second Avenue Sagas and Yvonne Carney, Director of Performance Improvement at the D.C. Metro.

Companies like Transit are showing how data can improve the rider experience. Transit agencies could follow that lead in their communication with riders, but they are often wedded to internal metrics that don't translate well to the rider experience.

"There's sometimes a disconnect between the data that the agencies collect for themselves and the data they present to the riders, and how they present it to the riders," Kabak said. "For the most part, most riders don't care about on-time performance, they don't care about headways, they don't care about terminal performance. They want to know how long it's going to take them to get somewhere, when their train or bus is coming, and if there are any problems along the route."

In the DC region, Carney said, it took a major crisis at WMATA to provoke the shift from on-time performance, a measurement of how actual train service compares to schedules, to a metric called "rail customer travel time," which better captures what riders experience. In the last year, the agency also rolled out a new trip planning app that provides more accurate travel and arrival times.

"[It] very much was customers saying, 'We want better information,'" Carney said. There was also a push from the agency's board. "Our board of directors has wanted us to provide them information to help them in their oversight of our organization. That has really been one of the main drivers of us presenting information. As we've done that, we've evolved how we give that information from being highly technical to... ways that resonate with the customer."

Faced with its own crisis, the MTA has started to adopt more rider-friendly performance metrics.

But the data available from the MTA still leaves a lot to be desired, Kabak said. Arrival times on Bus Time and, on certain lines, Subway Time are calculated by algorithms that mostly rely on distance. This fails to adequately factor in other variables, like traffic congestion. Riders can check their phones to see if a given subway line is delayed, but don't know how severe those delays might be.

And while countdown clocks are proliferating on train platforms, they often poorly-placed and limited to displaying the next one or two arrivals. On platforms where passengers wait for as many as four different lines, that's not enough.

"We're sort of living through a plague of inaccurate data [in New York], where either service alerts aren't updated in real-time, or the algorithms aren't correct," Kabak said.

Transit agencies might hesitate to release more robust data, because that can make riders more aware of the system's shortcomings, Kabak noted. But that's a fear agencies have to overcome if they're going to improve the rider experience.