The Department of Transportation presented the findings [PDF] of its five-year study of transportation in the Hell's Kitchen neighborhood at a packed public meeting last night. The massive transportation analysis included many critical projects that have already been announced, such as the 34th Street Select Bus Service route and extensions of the protected bike lanes along Eighth and Ninth Avenue, as well as a full slate of new improvements for the neighborhood, from signal retimings meant to improve pedestrian safety to new plaza space and a continuous sidewalk by the entrance to the Lincoln Tunnel.

The neighborhood study emerged from a pedestrian safety campaign conducted under the banner of the Ninth Avenue Renaissance, which started in 2006. DOT received federal funding for a study, solicited hundreds of public comments, walked through the neighborhood five times, built a powerful traffic model for the complicated Midtown area and analyzed 86 separate intersections.

Certain improvements were implemented as DOT studied the neighborhood. Leading pedestrian intervals, which give pedestrians time to establish their presence in a crosswalk before traffic gets the green light, were installed at six dangerous intersections, while pedestrian signal times were extended to provide for slower walkers.

Some of the biggest changes within the study area, which runs from 29th Street to 55th Street between Eighth Avenue and the Hudson River, are projects that have already been announced. Select Bus Service along 34th Street will speed bus trips, add new loading space and shorten pedestrian crossing distances with new bus bulbs. The extension of Eighth and Ninth Avenues, by far the two most dangerous corridors for cyclists and pedestrians, according to DOT, is expected to significantly improve safety for all users.

Other improvements, though, will be brand new. Pedestrians will again be able to walk down the west side of Ninth Avenue past the Lincoln Tunnel under DOT's recommendation. Currently, the sidewalk is interrupted at 36th Street by an unsignalized tunnel entrance. "We would provide a crosswalk and a stop light for the traffic," said Andrew Lenton, the project manager for the transportation study.

Another sidewalk will be restored around the corner on 36th Street. "Right now, it's occupied by NYPD vehicles parking on the sidewalk such that you can't even walk," said Lenton. Under DOT's proposal, the sidewalk and parking lane would be turned into green space.

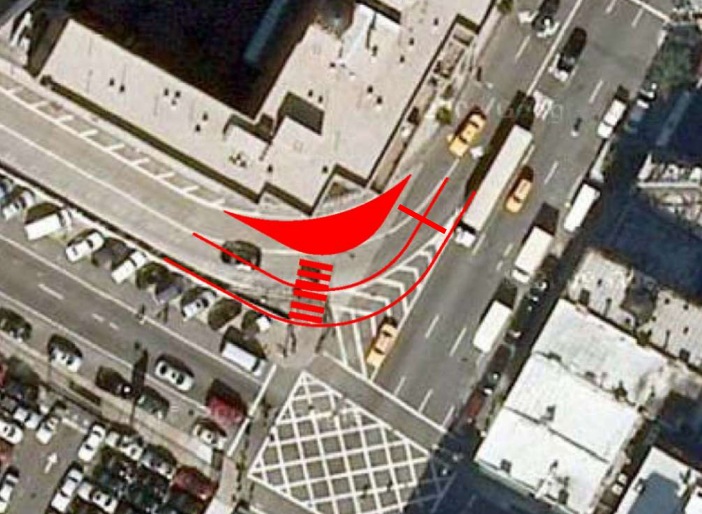

At Ninth Avenue, the two sides of 41st Street don't quite line up, forcing drivers to maneuver to the right and slowing traffic. By installing what they called a “mini-plaza,” DOT can smooth traffic flow while shortening crossing distances for pedestrians and creating new public space.

There was some conflict, however, over the possibility of creating additional pedestrian space on Dyer Avenue between 34th Street and 35th Street. DOT proposed closing the northbound lane of that block to traffic during the afternoon rush. When the northbound lanes were closed due to construction in 2009, the Port Authority noticed improved flow into the tunnel during peak hours. Many community members called for making the lane closure permanent and DOT said it supported the idea. "We agree. What's the point of banning it for PM only if the advantage is you get that extra space that you can take away from roadbed and give to pedestrians?" asked DOT engineer Greg Haas. But, said Haas, the Port Authority didn't want to see a permanent closure in case it decided it wanted the lane reopened. "They want it to be there, just in case," he said.

The plan also includes some small but important improvements for buses heading to the Lincoln Tunnel. During the afternoon peak period, the existing southbound contraflow bus lane on Dyer Avenue will be extended by one block, from 41st Street to 42nd Street. Currently, 60 buses an hour zigzag from 42nd Street onto Ninth, then 41st, and then Dyer. Extending the bus lane would allow buses to make a single turn instead of three. Similarly, making the right turn from Ninth Avenue to 41st Street bus-only all day long, instead of only during the afternoon rush, will prioritize bus access to the tunnel.

In general, the city's proposals were met with enthusiasm. "We are pretty excited," said Christine Berthet, the co-founder of the Clinton Hell’s Kitchen Coalition for Pedestrian Safety. However, Berthet and many pedestrian safety advocates were disappointed to see DOT opt to use leading pedestrian intervals at five dangerous intersections rather than split phases. LPIs give pedestrians a head start into the crosswalk while split phases mark off separate periods for pedestrians and turning vehicles to move. "In theory, it sounds good," Haas said of split phases, "but they're not as good as they're cracked up to be. There's a lot of non-compliance." He argued that on the East Side, where split phases are in use, pedestrians see the light for crossing traffic turn red and step out into the crosswalk just as a green arrow sends turning cars in their direction.

DOT agreed to install a split phase at 43rd and Ninth, however, and monitor its effects. If it's successful, it could be expanded to other intersections, said Haas. Berthet said she would continue to push for split phases. "We've been clamoring for split phases," she said. "They're the only way to protect the turning movement."

Many were also concerned about DOT's lack of a timeline for implementation. While Borough Commissioner Margaret Forgione said that easy changes like signal retiming would be put into place shortly, there is no construction schedule for changes like the 36th Street green space or new Ninth Avenue sidewalk.

Additional safety improvements could be added on top of the study's recommendations in the near future, however. Under DOT's Safe Streets for Seniors program, the area between Broadway and Ninth Avenue is slated for additional safety upgrades, which Forgione said will be put together over the next couple of months. Where the transportation study included pedestrian refuge islands along the new bike lane, for example, the senior safety program might install a neckdown on the other side of the street to narrow crossing distances.