If you build it — even temporarily — they will come.

The number of cyclists using Vanderbilt Avenue dramatically increases during open street hours when there's a safe route for cyclists — evidence that protected space for cyclists must replace painted lanes that drivers often swipe for parking, advocates said.

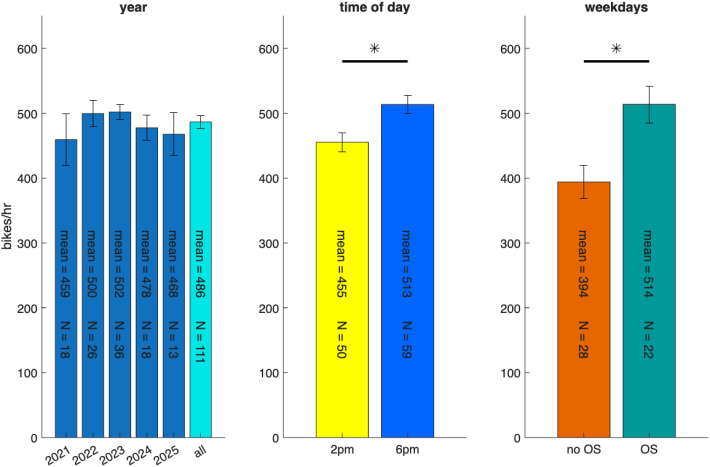

Between 2021 and 2025, Vanderbilt open street volunteers counted the number of cyclists traveling between Dean and Bergen streets, and between Prospect Place and St. Marks Avenue at 2 p.m. and 6 p.m., on days when the open street was active ... and on weekdays when it wasn't.

The bike counters found that there was an average of 486 cyclists per hour on Vanderbilt overall — evidence that cyclists want to use Vanderbilt. But they especially want to use it when the open street is in effect: there were 514 cyclists per hour during open street periods vs. 394 cyclists per hour when the roadway is almost entirely set aside for cars, save a narrow painted bike lane.

The numbers are comparable to the 2,600 cyclists per day that use the Prospect Park West bike lane, and also compare well to the bike counts the DOT itself did in 2021, when it counted 406 cyclists per hour on Dean Street and Vanderbilt Avenue and 452 cyclists per hour on Bergen Street and Vanderbilt Avenue, more evidence of the importance of Vanderbilt as a north-south cycling connector.

"Those numbers are significant; they show that people want to be cycling even where the infrastructure isn't as safe as it could be," said Vanderbilt Avenue open street organizer Alex Morano. "Now imagine if you really invested in trying to make this infrastructure good."

In theory, the city is working to make Vanderbilt more welcoming to people walking and cycling. Vanderbilt between Atlantic Avenue and Grand Army Plaza, and Underhill Avenue, are part of a larger DOT project to reconfigure Gand Army Plaza and its surrounding blocks. The city revealed a pair of options for that redesign last year, including one that would connect the plaza to Prospect Park, the way that Olmsted and Vaux originally wanted it.

The DOT also said it was considering a few different options for Vanderbilt and Underhill, including protected bike lanes, pedestrian plazas or even a busway.

Last June, the DOT laid out a timeline for the work, but has not said anything publicly since, though it has told local elected officials that it's been delayed because the agency doesn't have approval for a major capital project, according to Andrew Wright, the chief of staff for Council Member Crystal Hudson.

Redesigning Grand Army Plaza with a capital project was one of the Adams administration's ambitious ideas, especially because the city had gone as far as it was going to go with smaller scale paint-based ways to bring more pedestrian space to the plaza. Either design would bring some legible traffic patterns to the circle as well as potentially fixing the situation where pedestrians trying to cross between the park and the Brooklyn Public Library get stuck on an overcrowded concrete island surrounded by speeding traffic.

A spokesperson for the DOT did not comment on the status of capital money for the redesign, but did confirm the project is off schedule. "We are working to complete a traffic analysis and will share the results as well as more detailed design proposals in our next round of public outreach," an agency spokesperson said.

Facing yet another delay for an ambitious and interesting streetscape improvement, advocates pressed the next mayor to actually finish the job.

"Grand Army Plaza is a great public space that's currently bisected by dangerous traffic, marring Frederick Law Olmsted’s original design that envisioned the park and the plaza as one cohesive public space," said Transportation Alternatives Executive Director Ben Furnas. "The possibilities for improvements to this space are enormous, and the City — whether it's the current administration or the next one — should think big and be bold."