Gov. Hochul claims that she has "fully funded" the MTA's $68-billion capital plan, but in truth, the plan is a debt bomb at best and vaporware at worst.

Hochul spent the week touting a budget agreement with the state Legislature that includes a "fully funded" MTA repair plan for 2025 to 2029. Details on that aspect of the budget deal have been scant, but the governor has insisted that the state budget finally plugs a $35-billion hole in the capital plan by:

- Increasing the payroll tax on large businesses in the 12-county MTA service area (New York City, Long Island and the city's northern suburbs).

- Redirecting $1.2 billion previously earmarked for renovating Penn Station, which the Trump administration took out of the MTA's hands this month.

- Directing the MTA to pay $3 billion more than it was originally supposed to pay out of its own coffers.

Questions abound. It's unclear how much revenue will be raised via the payroll tax increase (and therefore how much it would allow the MTA to borrow towards the $68 billion). It's also unclear how the Janno Lieber-led agency will find the additional $3 billion, on top of the $10 billion it is already providing towards the plan with bonds backed by existing fares and tolls.

Hochul tried to explain the mysterious $3 billion hole at a press conference on Thursday, but her words were simply baffling.

"We're not saying. 'Find $3 billion in savings,'" the governor said. "It turns out that $150 million in savings can be bonded and leveraged for $3 billion more in improvements. I am very confident under Janno's leadership, [we'll] tighten the belts, find efficiency and we're going to continue seeing more revenues come in as our fare evasion strategies are unfolded and in every station."

Here is a quick lesson in municipal borrowing: You cannot borrow money, i.e. sell bonds, backed simply by money you don't spend. You can reduce your operating costs by $150 million per year, but you can't sell bonds based on that saving.

Which means that one way to understand Hochul's announcement is that it's an admission that the MTA will have to borrow even more money to fund the capital plan, on top of the $10 billion that the agency already planned to borrow. Riders ultimately fund the cost of the extra borrowing through their fares.

"What she's saying is that they need to hive off $150 million more a year for debt payments," said Reinvent Albany Executive Director John Kaehny.

It's also an open question as to whether the state will back up real efforts for real efficiency with real impact.

"The reality is, if the state leaders have agreed that the MTA should kick in, I certainly hope that the state leaders would support the MTA management in getting labor to the table to be more efficient," said Citizens Budget Commission President Andrew Rein. "They don't have to come to the table with lower wages, but they could help the MTA increase efficiency."

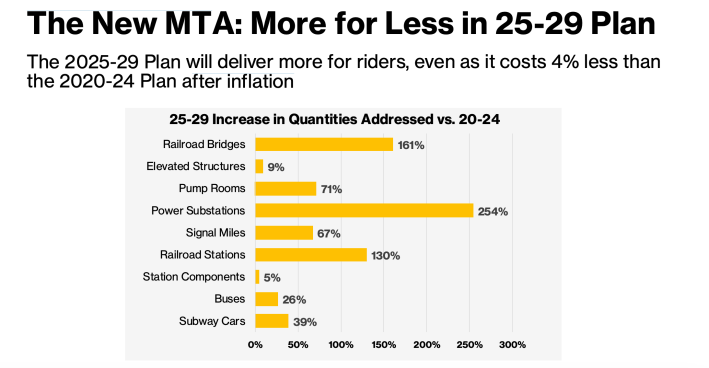

There is another option, which is to approve a $68-billion capital plan but then deliver it for $65 billion. Lieber suggested on Wednesday that officials really can find the $3 billion through efficiencies in the MTA's own construction work, because MTA Construction and Development has saved $3 billion since 2020.

MTA officials have bragged about how much more for less they will be able to deliver in the 2025-2029 capital plan when compared to the 2020-2024 plan. Officials also emphasize that the new plan actually costs four percent less than the previous one when accounting for inflation:

But even then, neither the MTA nor the governor characterizing the current capital plan as a $65 billion plan. The announcements this week have centered around a fully-funded $68 billion capital plan —with a $3 billion mystery void.

That void could have been smaller if Hochul hadn't cut the state and city contributions to the capital plan by $1 billion each from what the MTA initially proposed.

"We know that the $3 billion is still undefined," Rein said. "We should understand the roots of that $3 billion."