The most important transportation official in America said he thinks bike lanes cause congestion, decrease road safety and don't even result in more people riding — and questioned whether there's even data to disprove his suspicions when his own agencies actually have reams of it.

Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy's ill-informed answer at the 2025 World Economy Summit came after Semafor White House correspondent Shelby Talcott asked the ultimate Streetsblog question: Why is the U.S. DOT reviewing all bike-related government grants and programs? Is the federal government trying to reduce bike use?

First, Duffy grimaced and grumbled, expletive-style, "Bikes," before spewing a gut impressions about bike use that are all-too-common among people who only get around by car.

"I'm not opposed to bikes," he started, before revealing his opposition. "But in New York ... they want to expand bike lanes, and then they get more congestion. ... What are the roads for, and how do we use our roads? If we put bikes on roadways, and then we get congestion, it's a really bad experience for a lot of people.

"I do think it's a problem when we're making massive investments in bike lanes to at the expense of vehicles," he added. "I do think you see more congestion when you add bike lanes and take away vehicle lanes. That's a problem."

(The full answer was a thing to behold, so we recommend that you watch it in full here):

He also went on to say that bike lanes are "really dangerous for bikers" in urban areas and that Europe, which has made cities more livable due to massive post-gas crisis expansion of bike lanes and pedestrianization, is not worth emulating, despite its lower road fatality rates.

"We don't have the same mentality as Europeans do, and so I don't think we should necessarily buy into the European model," he added (oddly seconds after praising European high-speed rail in an earlier answer).

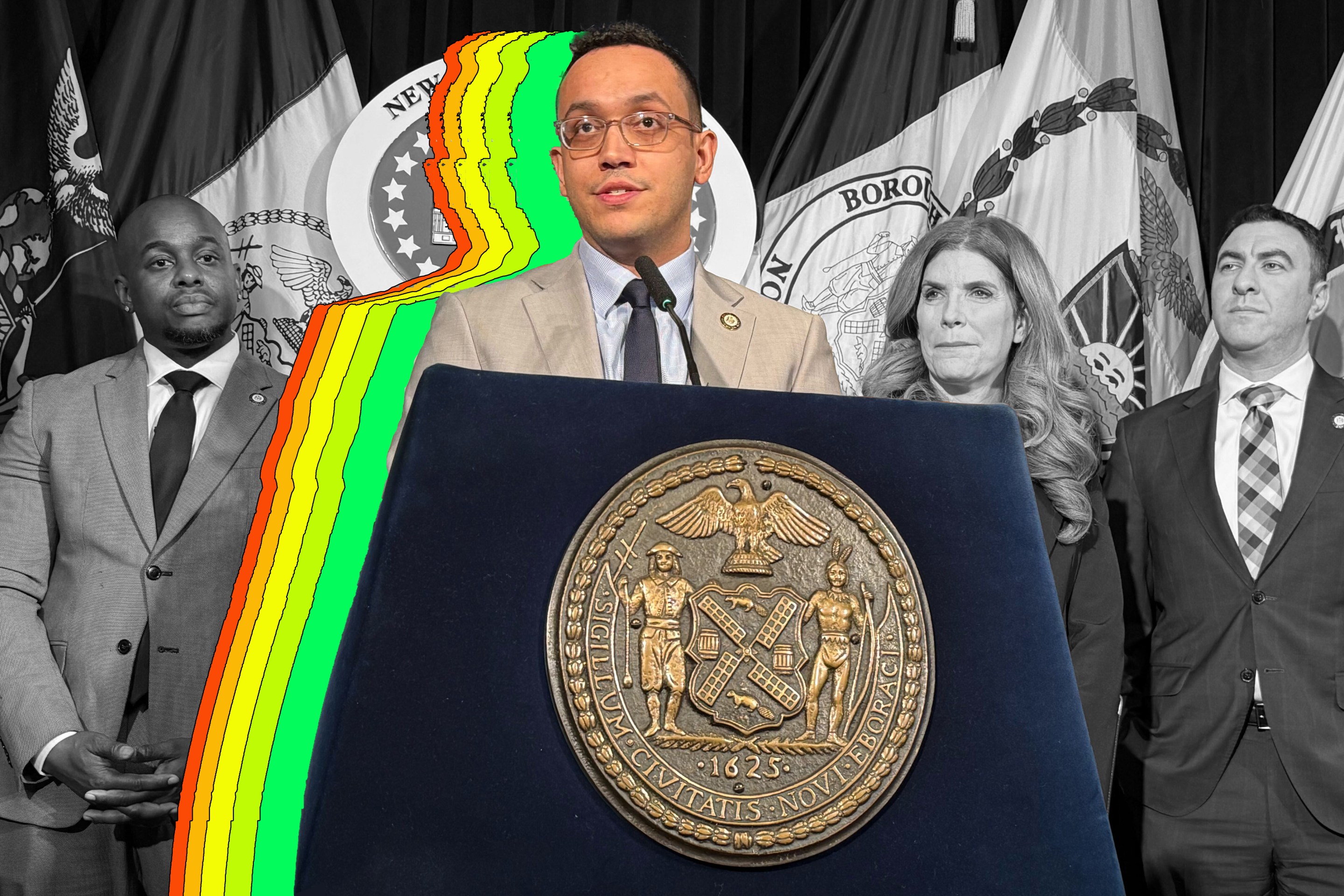

Duffy acknowledged "there's some places bike lanes might make sense," but his repeated mention of New York City ignored how much sense street redesigns make for the Big Apple in particular. Reams of data show the city's protected bike lanes reduce traffic injuries while encouraging more people to bike (including drivers). A 2020 study found the city's protected bike lanes actually improved traffic speeds.

The good news? Duffy said he'd be willing to "look at data" and if the data show that bike lanes saved lives and reduced congestion, "we should do more bike lanes."

Fortunately for the secretary, Streetsblog has been providing data on the benefits for bike lanes (and the stubborn myths that tend to follow them) since 2006 — including decades of data on this very topic that his administration recently scrubbed from federal websites.

Here's a point-by-point explainer for the Secretary, and anyone else who needs one, starting with his most pressing questions.

Do bike lanes save lives?

First things first: what does Duffy even mean by "bike lanes"?

If he means "high-quality, separated bike lanes that physically divide motorists from vulnerable road users they might strike," the answer is a resounding (and pretty damn intuitive) yes.

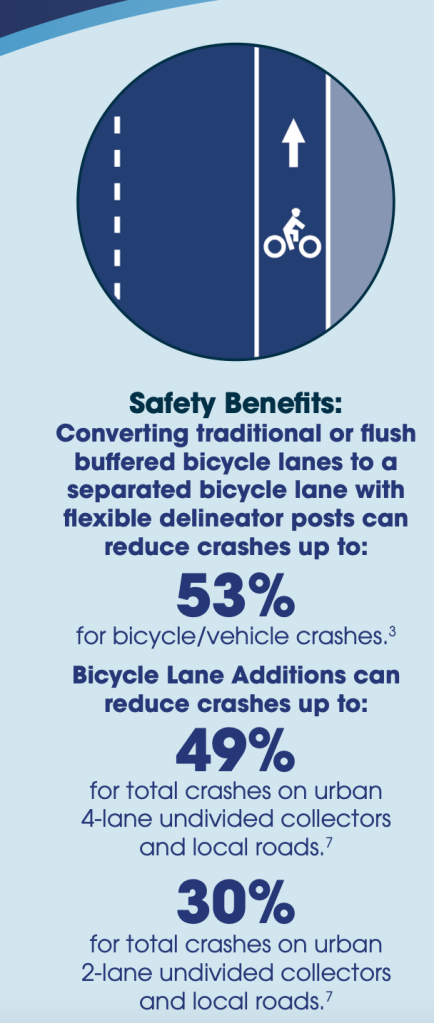

The Federal Highway Administration's own website on bike lanes says that even just adding flexible plastic posts to paint-only on-road cycle paths can reduce total crashes up to 53 percent — and putting harder infrastructure like concrete jersey barriers or curbs between motorists and fragile human bodies is so much better that most researchers don't even bother to study it.

Even paint-only bike lanes are shown to save lives, with one FHWA study showing a 49-percent reduction in total crashes on urban four-lane, undivided collectors and local roads after striping went in. On two-lane, undivided urban collectors, those roads still showed a whopping 30 percent crash reduction.

Those are total crash reductions, by the way, not just those involving cyclists — and again, those are all studies of the least protective of bike lane designs, not the high-quality, separated kind that cyclists across the country are demanding, and that U.S. DOT can help cities build on the cheap. Here's a simple example from Duffy's home state of Wisconsin as a visual aid:

Imagine what Duffy could do if he put in more lanes like these.

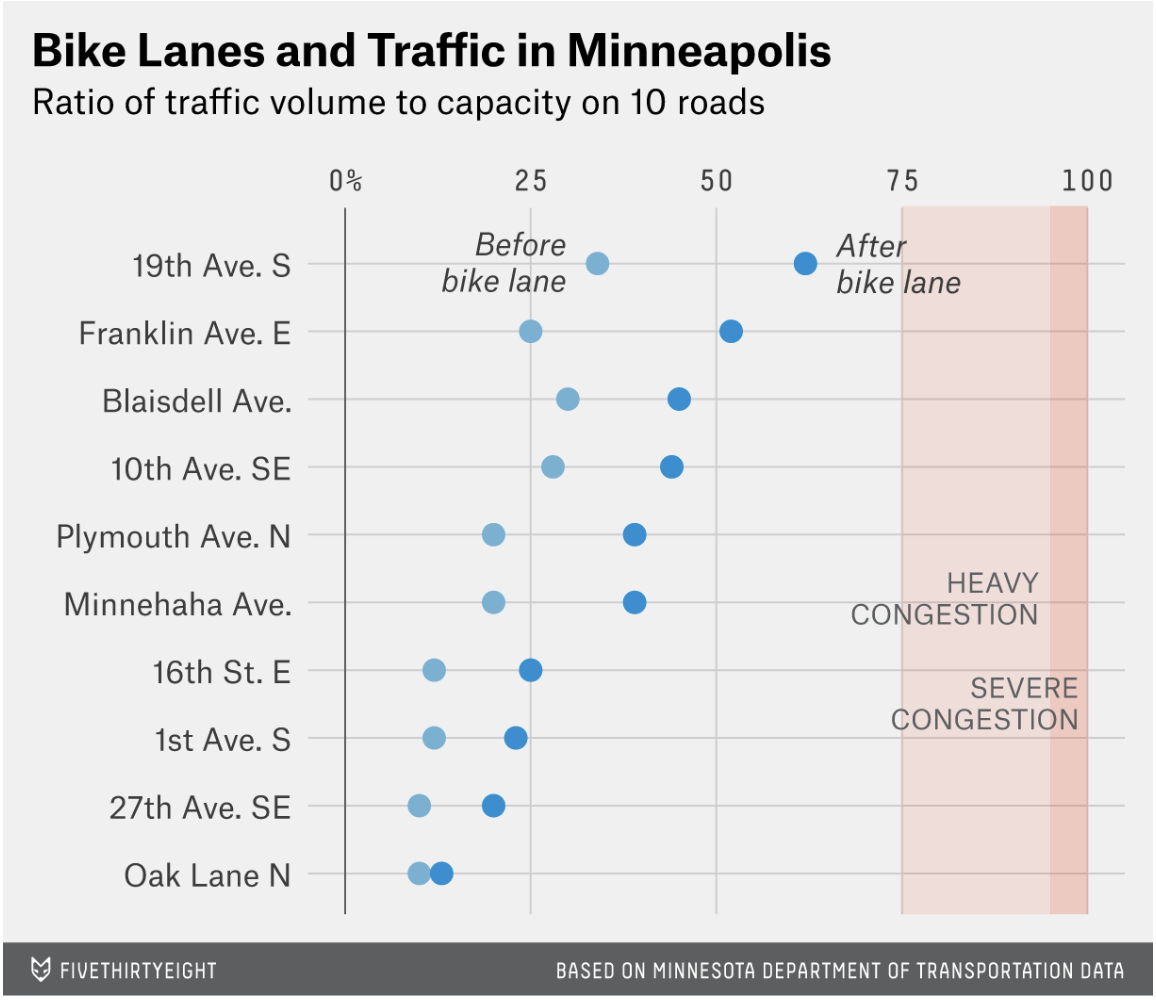

Do bike lanes increase congestion?

This is a hard no. No, bike lanes do not increase congestion. Let's go back to that same FHWA bike lane page for our answer.

Studies have found that roadways did not experience an increase in crashes or congestion when travel lane widths were decreased to add a bicycle lane.

Basically: if you give residents of a city a big-enough network of safe bike lanes to the places they need to go most, a lot of them will choose to leave their cars at home for short trips, or even sell them altogether — which means fewer automobiles jamming up the roads, and faster speeds for the drivers who remain.

It can take a couple years to get there — and yes, you do have to have a network of lanes, rather than just one or two paths to nowhere, to see real traffic-cutting benefits. But study after study shows that bike lanes do not make car congestion worse— and in some cases, especially in urban areas that place them strategically, they can actually make it better.

Meanwhile, a century's worth of research shows that adding or preserving lane space for drivers might speed up cars for a little while, but in the end, it invariably just encourages more driving — especially in urban areas, as would-be bikers and walkers take to cars instead, because they're terrified of being violently killed by a motorist in an unprotected lane. (That phenomenon is known as induced demand, and it's true on highways too, but we'll save that for another explainer.)

In New York City, the opposite has occurred: When officials repurpose space away from cars, many of these automobile trips disappear, explains former city Traffic Commissioner Sam Schwartz.

New York City DOT under Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan "did many things that did reduce capacity and as a result of all of those things, about 100,000 fewer cars were coming in," Schwartz told Streetsblog in a recent interview.

"The reason speeds didn't get better was that simultaneously Uber and Lyft came into being as well as Amazon deliveries," he explained. "The bike lanes and bus lanes and others cause fewer cars to come in. If we remove the bike lanes and bus lanes, we're going to increase capacity — and what we see time and time again is that additional capacity increases traffic."

Do bike lanes encourage riding?

Look, we understand why so many drivers like Duffy see a single empty bike lane on a rainy day, grumble that no one's even riding in it, and demand that the space be given back to drivers. But reams of research show that good bike lanes do get people riding — especially if they're separated and connected to a network of other bike lanes that actually get people where they're going.

If Duffy is really interested in making "data-driven decisions," our friends at People for Bikes have a boatload of city-specific stats about how building bike lanes right does induce more riding, including how D.C. and New York City doubled their bike commute rate in just four years when they started building lanes.

But we'd encourage the secretary to recognize the unique position he's in to start the bike lane revolution in American cities, even if those first few, disconnected lanes don't spur an immediate jump in ridership — and work with Congress to give cities the flexibility and funds they need to fill in the gaps that really get people in the saddle.

We won't spend as much time on the other misconceptions in Duffy's comments, which are too lengthy to reproduce in full here, but here's a quick cheat sheet on a few in case it's helpful:

Are we really 'making massive investments in bike lanes at the expense of vehicles'?

Nope! Per the League of American Bicyclists, less than 2 percent of federal transportation funding is spent on biking and walking combined, amounting to $2.36 per person per year.

Is it true that 'we're not Europe' and 'we don't have the same mentality as Europeans do' because our vehicle sizes are so big?

If only we knew someone who had direct control over the regulatory policies that dictate our vehicle sizes, who was also uniquely positioned to influence the American traveler's mentality about how how they get around ... like the Secretary of Transportation. 🤔

Seriously, though, most of Europe was once every bit as car-dominated as America remains today. And if Duffy's looking for inspiration for how countries on other continents are confronting car dependency, we've got you, too:

Is it true that bike lanes aren't use in northern cities where it gets 'awfully chilly'?

Lucky for Duffy, we wrote a whole essay about exactly this!

But basically: if you remove enough of the year-round barriers to biking by building protected lanes and great, bike-supportive policies, people can and do bike in the depths of winter, and the blistering heat, and the pouring rain — and there's a mountain of global evidence to prove it.

Finally, is Duffy's demand for 'hard data' about the benefits of bike lanes just a bad-faith lie to obscure his own opposition to infrastructure that he thinks doesn't benefit drivers, especially considering that he oversees a department that has produced decades of that exact data?

Yes! But if it's true that Sean Duffy somehow became the literal secretary of transportation without learning anything about one of the most basic and ancient modes of travel, it's never too late to teach him – and he has nearly 20 years of Streetsblog content (and data that his own agencies are hastily scrubbing from their websites) available to help him study up.

With reporting from David Meyer