The 2017 “Summer of Hell” has haunted Gov. Hochul’s bizarre string of decisions to “indefinitely pause,” then reactivate, congestion pricing — igniting concerns that delays to urgent repairs could snowball into a repeat of that crisis summer of delays, derailments and chaos.

But with yet another Albany-created “crisis” in progress, it’s worth asking, given the MTA’s constant string of service delivery and funding problems, whether money alone is enough to solve the New York region’s transit problems — or if the New York region needs to fundamentally change the way it governs its transit system.

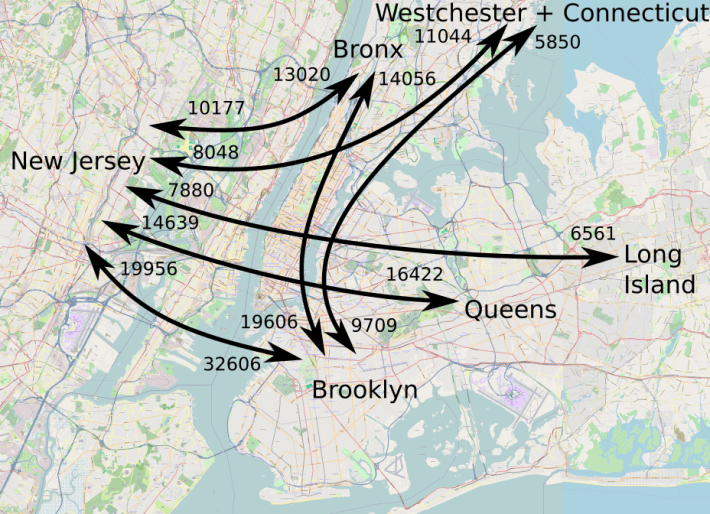

A crisis comes and goes. What we have here is different: The MTA, and by extension the entire tri-state region, are in a perpetual state of transportation emergency. Viewing the system in terms of any single summer or year of high-profile service problems misses key context — namely, the lack of any regional governance arrangement. New York’s transit system is chopped into bits. That encourages parochialism, rather than collaboration, and pits states, cities and counties against one another.

The scale of challenges is too enormous to pin on one person or political moment; they’re symptoms of a Balkanized system. Escaping the constant string of crises not only requires the revenue from congestion pricing, it also must include governance reform that fosters collaboration across agencies and state and city lines.

Some of the region’s most respected experts have called for exactly that.

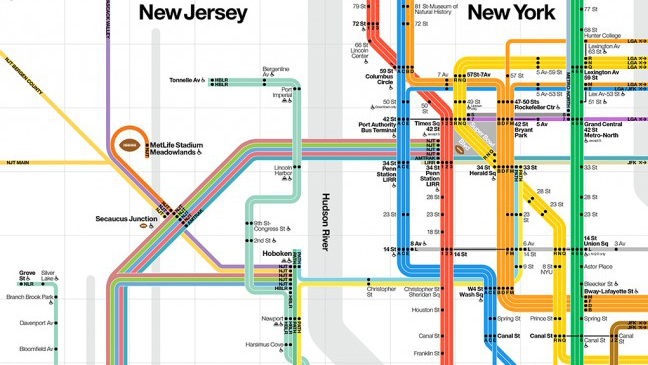

In November, Streetsblog published a proposal from three senior ex-transit officials arguing for a new regional agency to combine the region’s disparate railroads into a single joint operation. The Regional Plan Association has proposed a similar “Trans-Regional Express.” This hypothetical agency would oversee major improvements connecting and expanding the region’s shared infrastructure like through-running at Penn Station. Having trains run across the whole region, instead of ending at Penn or Grand Central, would create better services, increase ridership, integrate fares, and simply make sense by easing access to housing and employment across anachronistic state and city boundaries.

But reform of that caliber requires buy-in from three governors’ offices, multiple agencies, local governments and probably Congress. Our leaders will need to be convinced that there even is a regional governance problem. Still, assuming the need for reform is recognized and the will for reform is there, what examples can the tri-state lean on to improve its own transit governance?

National and international examples of different regional transport governance arrangements present pathways to reform. Generally, they fall into the following three categories:

- Regions that have one transit agency run everything, including American cities like Boston, Denver and Phoenix.

- Regions like London, Toronto and Paris that have one “network manager” coordinate all the transit agencies while also running their own services.

- Regions that have a central agency coordinating individual transit agencies, like the German Verkehrsverbünde and the Skånetrafiken in Sweden’s Scania province.

The most politically realistic path towards system-wide reform lies in the third option — a network manager coordinating pre-existing agencies — but there are examples across all types of arrangements to consider, particularly for each of the current and future agencies themselves.

We know this can be done from experience, namely the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. The Port Authority provides a few services of its own (the JFK and Newark AirTrains, plus PATH connecting Manhattan and New Jersey), but its innovation when it formed in 1921 was really around the idea that shared, revenue-producing assets like ports, bridges, tunnels and airports required regional, bi-state oversight. But the Port Authority’s governing structure — a board of commissioners appointed by the governors of each state — is prone to political interference from governors.

There’s precedent for a politically independent regional planning agency in Portland, Oregon, where Metro is the only directly elected regional council in the country, giving residents unmatched influence in transportation planning decisions. Metro’s jurisdiction is limited to the part of the region in Oregon, however, excluding the half of the Portland area in Washington State. In the nation’s capital, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority has an explicit regional, interstate mandate. The transit authority’s board is designed to balance power among D.C., Maryland and Virginia, promote regional governance and eliminate service redundancies. Creating WMATA allowed D.C. to build a regional subway and fuse multiple private bus operators.

A different approach to regional governance reform, and one that has merits regardless of whether a new regional rail agency comes to being, is what the Germans call the Verkehrsverbund. The literal translation is “transit association,” but the Verbund acts more like a network manager coordinating fares and schedules for a metropolitan area’s transit services. Given the parallels between the German and American federal systems, such an arrangement would do some good for regional governance, particularly those stretching across state lines with dozens of transit agencies.

Berlin and Brandenburg’s joint VBB, for example, covers two states and coordinates over 30 agencies delivering subway, tram, regional rail and bus services. VBB is technically a private entity co-owned by both states and the counties and cities within Brandenburg. The agency isn’t perfect or immune to criticism, particularly in the wake of recently announced fare hikes, but it allows the region to coordinate like one, all the more essential when the federal government is collapsing or can no longer be trusted.

What unifies these structures is a recognition that a region’s value is greater than the sum of its parts. Governance reform proposals in that vein — even those we’ve yet to see tested elsewhere — deserve consideration. Otherwise, we’re assured a fate of leaping from one seemingly temporary crisis to another with the big governance questions on standby, or worse: forgotten.