A business-led push to restore private car traffic on Park Row will encourage more driving and traffic in the area, city transportation officials said, and Chinatown residents worry the move will undercut efforts to make the area more welcoming for residents and visitors.

Local business groups and some politicians have long pushed to allow cars back on the street that's been restricted to most vehicles since 9/11, with one area lawmaker proposing as many as four lanes on Park Row, but a Department of Transportation rep recently told Community Board 1 that the pro-car move would only result in ... more cars.

"We do estimate that there will be additional volume in the network that is not currently in the network," Casey Gorrell, the acting Design and Capital lead at DOT’s Public Realm unit, told CB 1's Transportation and Street Activity Permits Committee on Nov. 6. "Creating a new roadway will create more traffic, not just shift it around."

The official's forecast is no surprise, given that adding space for car drivers typically encourages more of them to drive, a phenomenon planners call induced demand. The agency plans to release more specific impacts of reopening Park Row between the Brooklyn Bridge and Worth Street next month.

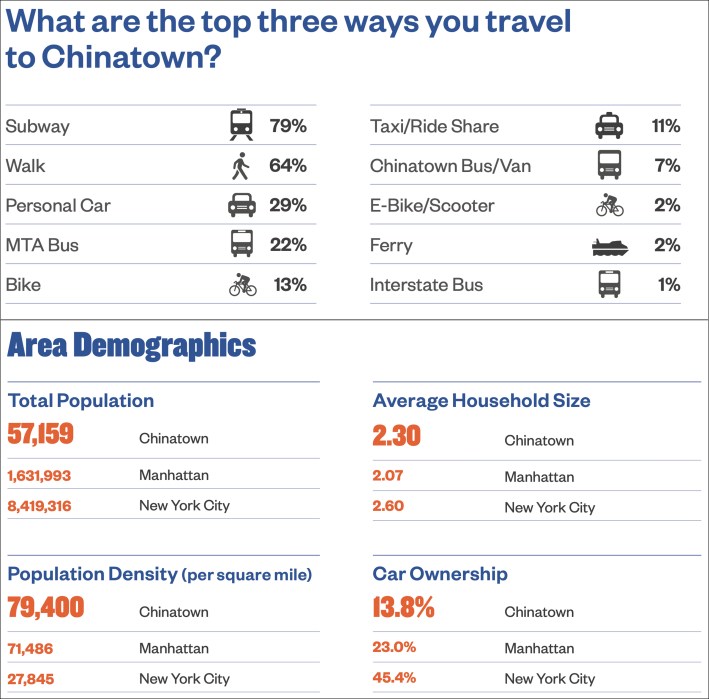

More vehicles is not what the area needs, residents say, given that the vast majority of people in the neighborhood don't drive and instead get around on foot.

According to DOT data, a whopping 80 percent of people passing through the area are on foot, but they only get 37 percent of the street scape.

Chinatown's population is older, poorer, and has a lower car ownership rate than Manhattan as a whole, according to a report by local business groups and the Department of Small Business Services [PDF].

One senior told Streetsblog she would no longer venture onto the road if it refills with cars for the first time in 23 years.

"I would not feel safe, I would never use Park Row again if the street was open [to cars]," Felicia Castiglia, who has lived there for 50 years, told Streetsblog. "I use Park Row quite a bit because I use it to get downtown, to get to the hospital, to get to my doctors, it’s a very nice way to get to downtown."

An area youngster recently also asked the city at a different community board meeting to keep the road free of cars so that she and her dad could safely walk and bike through the area.

"It is a bad idea to open Park Row because the little kids that live here might cross the road and one of the drivers in a car may not see the little kid crossing the road," said Amelie, 7, at a Community Board 3 Transportation Committee meeting on Nov. 11. "When my dad is taking me to school, the cars will block his way and the cars can hit us."

A group in favor of keeping the corridor car free called the Coalition to Keep Park Row Safe has also sent more than 3,300 letters to local electeds, according to a petition website.

Business leaders often mistakenly believe that more auto traffic is good for their bottom line, but recent examples of the city reclaiming space from cars for people have yielded the opposite effect.

DOT's Open Streets locations consistently had lower storefront vacancies than the city as a whole, according to a recent report by the Department of City Planning. Chinatown's own car-free corridors like Pell and Doyers streets fared far better than their car-friendly neighbors during the pandemic, according to a separate DOT report, and business has been booming on similar setups from Canal Street to Columbus Avenue.

Park Row's closure dates back to police sealing off the area around their headquarters at 1 Police Plaza for security reasons following the 2001 terror attacks. Cops and officials at the nearby courthouses have since seized much of the streets as their own campus to park their vehicles.

The Adams administration has been reexamining the roughly third-of-a-mile corridor as part of its $56 million overhaul of the adjacent Kimlau Square, but elected officials including Council Member Chris Marte and Rep. Dan Goldman have been trying to get Hizzoner to also bring back cars to Park Row.

The city's recent focus on Chinatown was prompted by a $20-million state grant in 2022 to revitalize the neighborhood's businesses hurt by the pandemic.

Transportation officials have been studying the likely effects of returning car traffic to Park Row for months. In the meantime, DOT has tried to reduce the checkpoint-style security zone vibe of the corridor and make it more enticing, by adding colorful paint jobs to its sidewalk extensions and along the walls of a dark staircase at the Brooklyn Bridge, while moving illegally parked cop cars off the sidewalks by marking a wide two-way parking-protected bike lane.

Officials also plan to widen a pinch point painted sidewalk that pedestrians and cyclists currently share.

The facelift has already worked wonders by drawing more people to Park Row, said Rosa Chang, the President of Gotham Park, a group that has been partnering with the city to restore access to shuttered lots by the Brooklyn Bridge.

"The amount of people that are going through these spaces are increasing so much and I am personally shocked," Chang said at the recent CB 1 committee meeting. "This is starting to feel like a space that is occupied and utilized, and hopefully will be delivering lots of foot traffic to the neighborhood."

Mayor Adams unlocked the first closed-off space between Park Row and Rose Street last year. Another slice of land adjacent to the bridge opened Monday, after being closed to the public for a decade due to contractors occupying the space while restoring the 141-year-old bridge.

A section to the east that was once a popular skate spot known as the Brooklyn Banks remains behind a fence and littered with construction materials, but its gate was open Monday afternoon. DOT has applied for federal grant money to fund the reopening of more of the lots, the agency said in a press release.

DOT plans to release interim results from its traffic study in December, and finish up a full report by early next year.