Time to put the vision in Vision Zero.

The city could trim lengthy project timelines for safe street infrastructure if transportation planners adopted the latest technology for traffic analyses rather than relying on ancient methods, a new report issued by City Hall argues.

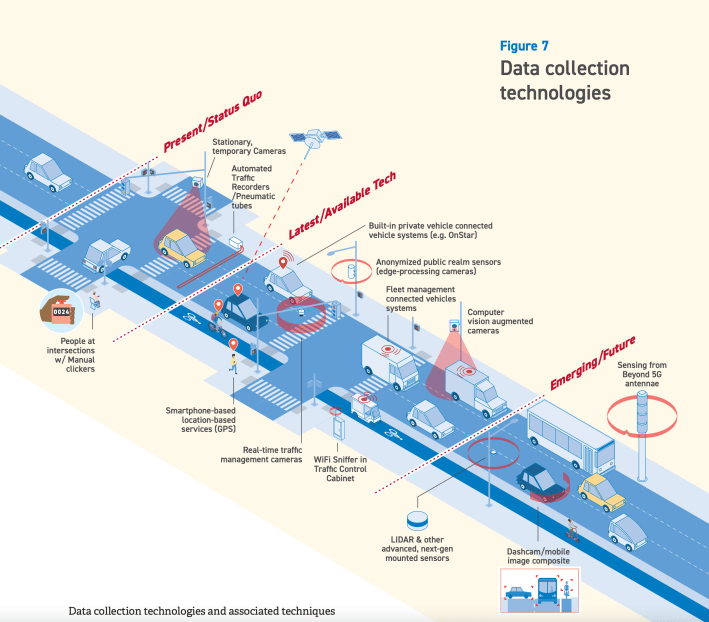

The Department of Transportation still uses analogue methods like manual clickers and pneumatic tubes for its months-long traffic studies, which could accelerate to just matter of hours if the agency modernized its ways, according to a recent written by Cornell Tech.

The study, "How NYC Moves" [PDF], was actually issued by Mayor Adams's office even though it argues that DOT — an agency Hizzoner controls — should modernize. For instance, the report argues that the agency should create a centralized citywide traffic database, similarly to those by private companies like Replica or StreetLight. And the city should tap into the tens of thousands of street-facing cameras, along with information from sensor-equipped vehicles, and anonymized cell phone GPS data.

Currently, the agency sends out staffers for each project to set up temporary cameras, take measurements by hand, and lay out sensors on roadways to count vehicles.

Tech improvements like that would "pretty clearly take something that takes four months — the data collection — down to just a look-up," said Paul Salama, one of the report's authors and an urban technology fellow at Cornell Tech. "That would be really a powerful reframing of how the process gets done."

Shortening study timelines for projects such as bus and bike lanes as well as housing developments leaves less time for opponents to derail them, Salama added.

"Having any delays of any sort leaves openings for things to not get done," he said.

There are other costs to the slow processes. Transportation studies are a key element of the city's environmental reviews that happen for major developments like new housing, and the studies can add 9 percent to a project budget, according to the Citizens Budget Commission, and advocates called on City Hall to listen to its own advice.

"DOT uses some pretty outdated systems for collecting data, which add time and money to that phase of a project, but technology has gotten much better," said Talya Schwartz, Lead Strategist for Urban Mobility at Open Plans (which shares a parent company with Streetsblog. "The city can absolutely update their guidelines and procedures to be more efficient, which will get them to implementation faster while still being confident that the data is accurate."

There is a network of tens of thousands of cameras operated by DOT and other agencies, such as the state's Metropolitan Transportation Authority, along with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

The MTA, for instance, installed cameras at 110 locations to prepare for congestion pricing — and even though Gov. Hochul stalled implementation, the machines are steadily counting traffic entering the central business district.

The city could use artificial intelligence programs known as computer vision to pull information, not just traffic counts, but also traffic patterns, from these video feeds, Salama said.

"There’s this base of 10,000-20,000 cameras across agencies," he said. "For legitimate and less-than-legitimate reasons, they’re not applying these technologies, computer vision, to do counting with those cameras because the structural barriers feel too high.

"Me as an outsider, coming from an academics lens, that’s kind of ridiculous," he added.

At a January symposium leading up to the report, DOT traffic engineering and planning representatives were skeptical about relying too heavily on these newer ways. The agency reps argued that those methods were untested and the data were not as reliable, and that they did not distinguish enough between New York City's complex array of traffic weaving through surface roads, highways, bike lanes, and elevated subway lines.

Big data sets did have some issues, the bureaucrats said, such as aggregating data into one-hour periods, rather than the 15-minute increments DOT uses to identify peak traffic hours. Computer programs sometimes spat out "wildly inconsistent results" and struggled to differentiate between traffic on a surface street and an adjacent elevated roadway, according to the report.

But those arguments should not hold back the city from trying newer methods, Rachel Weinberger, director of Research Strategy at the Regional Plan Association, said at the confab earlier this year.

"New data collection opportunities are unproven, but old ones are proven to be poor," Weinberger said, according to the report.

There are also potential legal risks to trying out new methods, Weinberger told Streetsblog. For example, if someone sued over a redesign that didn't rely on the tried and tested planning, a judge could take DOT to task.

"'Oh, well you’ve used an unproven technique,' so, bang, you’re responsible," Weinberger said. "A lot of times these things are blocked because the legal system is so insanely conservative."

A forward-thinking agency leader with a supportive mayor could start implementing these changes while still backing them up with the old methods, Weinberger added, citing the combination of former DOT Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan under then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg as an example.

"You might for a period of time do both," Weinberger said. "From time to time there’s a DOT commissioner who’s willing to take a chance [with] a mayor who supports them."

DOT spokesman Vin Barone said the agency endorses the report's recommendations, but argued that the study was more to "discuss" the new tech than implementing it "immediately."

"DOT supports the recommendations of the report, and we have been using, or exploring, many of these tools to more quickly and effectively gather data," said Barone in a statement.

The agency has been using anonymized connected vehicle and cell phone data "for years" for larger projects, but that the tech has "some limitations" discussed in the report, Barone added. Officials have also been piloting sensors for car, pedestrian and bike traffic at a dozen locations that could inform future street redesigns, the rep said.