New York City's narrow sidewalks are destined to be lined with giant walls of garbage cans if Mayor Adams doesn't shift gears to put new waste containers in the streets, according to a new report by waste management experts.

The Department of Sanitation's current plan to move trash collection from bags to sidewalk bins is a step forward, but it threatens to dump hundreds of the containers per block onto space currently reserved for pedestrians in denser parts of the city. That could undo the Adams administration's historic effort to remove the Big Apple's notorious mountains of rubbish, according to one of the authors of the new paper by the Center for Zero Waste Design.

"There could be a huge backlash [if there are wheelie bins all over the place] and we’ll be back to bags and it’ll be much harder to do it in the future," said architect Clare Miflin, the Center's executive director. "If they get it wrong, it might never happen."

New York's already crowded sidewalks will transform into "bin city" under the current plan, advocates previously warned. Instead of the mounds of stinking bags that currently pile up multiple times a week, we'll get a 24-7 obstacle course of containers.

But officials at New York's Strongest have resisted changes to the project.

DSNY instead plans to require large residential buildings with 31 or more units to put their garbage in European-style stationary containers in the curbside roadway lane, while 10- to 30-unit complexes can choose those or wheelie bins on the sidewalk, starting with a year-long pilot in upper Manhattan next June.

Sanitation officials hope that mid-size buildings opt largely to use street containers, not the wheelie bins. Smaller buildings of between one and nine units won't have a choice: They'll have to use wheeled bins on the foot path starting on Nov. 13.

The new 41-page report lays out in detail how the city could completely free its sidewalks of waste containers — except for litter baskets — with proposals for each building size.

Under the city's plan, a single residential block with 20-unit buildings would have around 600 trash and organics bins, the report warns.

"They’re just going to be full of bins and that’s going to make people think that’s not a good idea for New York City," Miflin said.

Sharing is caring

The Center published a similar report focused on the Vanderbilt Avenue Open Street in Brooklyn last year; the latest study tackles the issue citywide.

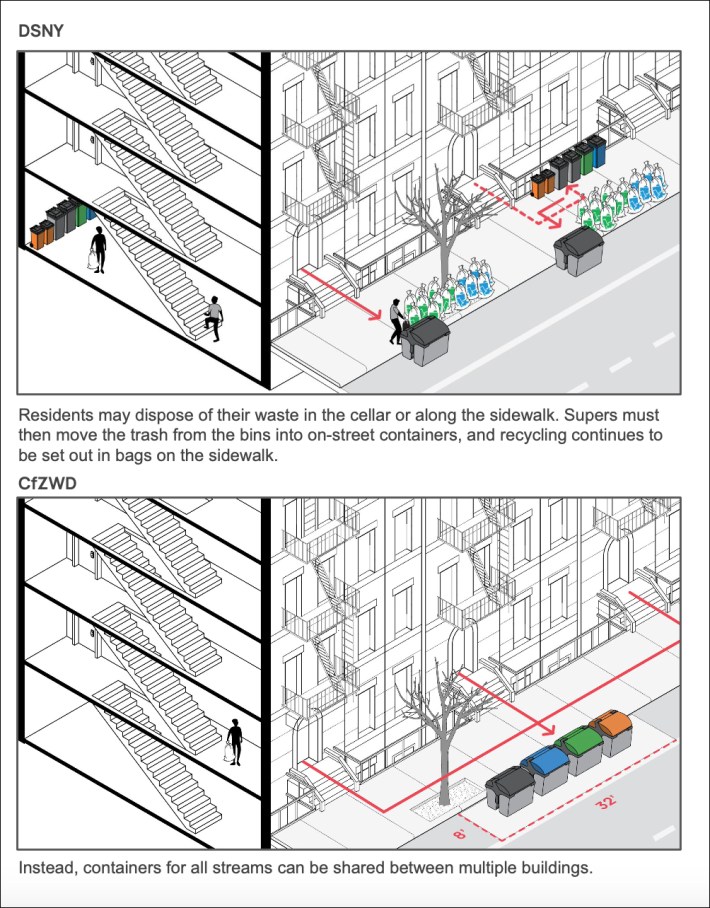

The city could keep waste — including recycling, which isn't part of DSNY's containerization plan — out of pedestrian space by allowing shared and moveable containers, according to the report.

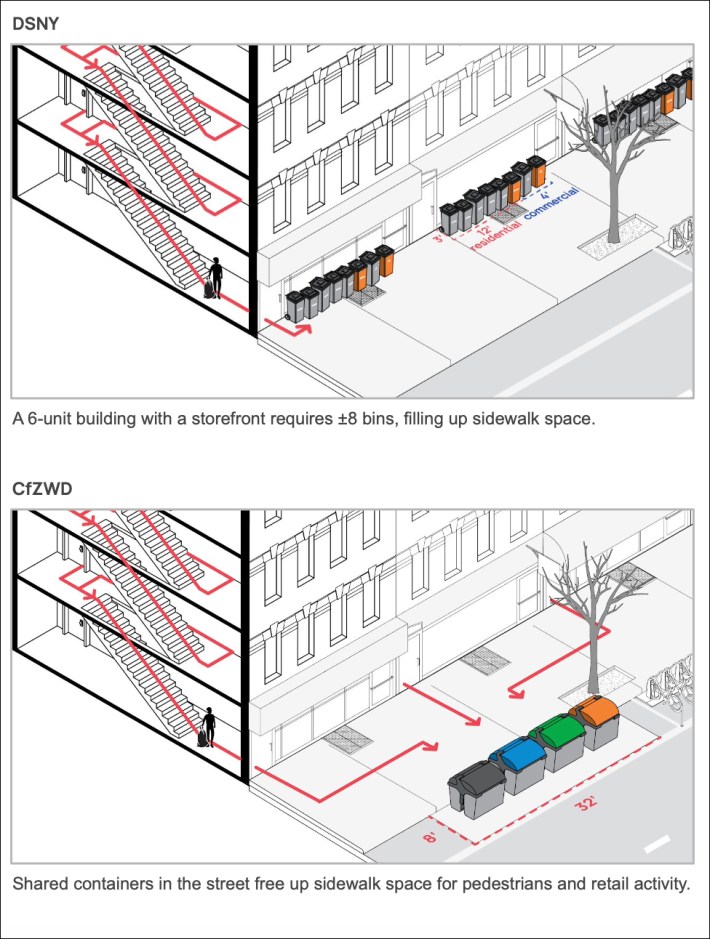

Wheelie bins work well for detached one-to-two family houses on Staten Island or in Queens, but rowhouses and larger housing stock up to nine units should also be allowed to use roadway containers, the report said. Buildings with six units could share just a handful of containers along the curb for trash, recycling, and organics, occupying fewer than three "parking" spots per block, rather than a wall of wheelie bins.

The renderings below show the difference between DSNY's plan and a curbside-only alternatives:

That's equally true for buildings with 10 to 30 units, where a few segments of curb space could serve several buildings. Under DSNY's plan, where each stationary container belongs to a specific building, trash from those building might take up more than one-third of the block length, according to the report.

The bins will likely only be half full on collection days anyway, the report said. If the city pursues its waste diversion goals for recycling, that rate could go down to 20 percent, so not every building needs its own a stationary container.

Under DSNY's reforms, recycling will still go in bags on the sidewalk, since those attract fewer rats than garbage or food waste.

Rolling rollout

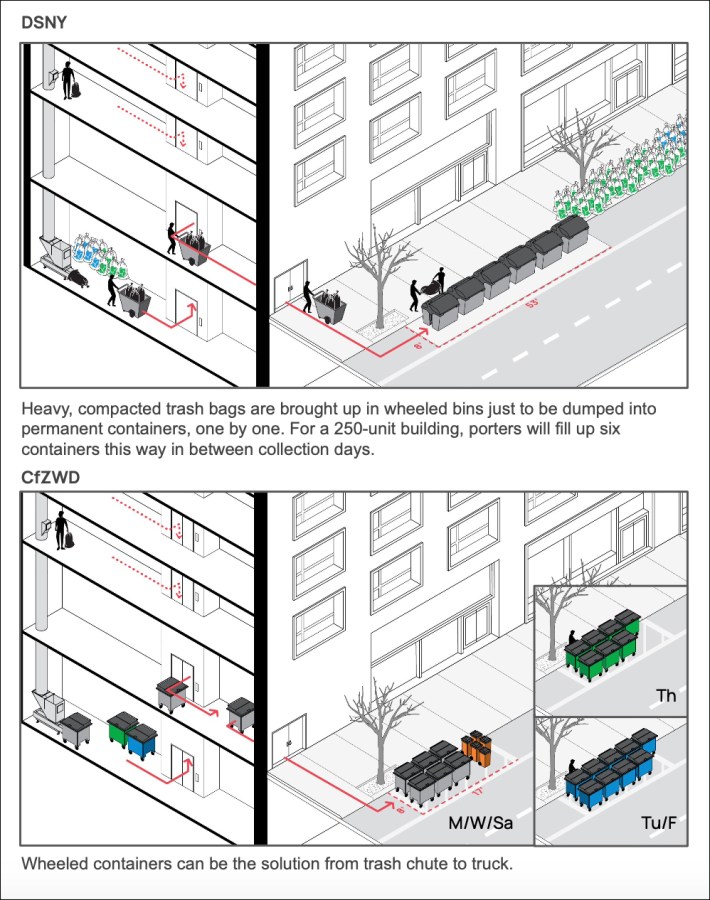

For the largest buildings of 31 units or more, which covers 51 percent of city residences, Sanitation plans to require bins in the street. But rather than the stationary versions, the city should go for rolling bins to free up that curb space for other uses between collections, the report suggests.

Many big developments, such as the massive 1,600-unit London Terrace complex in Chelsea, already use rolling containers to transport their garbage out to the curb, the report said.

That block-size building alone on W. 23rd Street, between Ninth and 10th avenues, will require 22 permanent stationary containers on the street for its garbage and more than 100 32-gallon bins for organics if DSNY expands its incoming regime to the area, the experts estimated.

Building staff there currently wheel out bins of trash bags and dump them in the street and sidewalk, but instead they could just stage the moving containers in four parking spaces during collection, and free them back up afterward.

"They’re already wheeling stuff out, why have to empty it again and put it in another [container]," Miflin said. "Many large buildings have storage inside, so why give them street space, it’s actually easier for them to wheel it out."

City pushback

The DSNY press office declined to comment on the report, but agency leaders have in the past resisted the idea of shared containers. Officials argue it would be easier to enforce against illegal dumping or other violations if each bin belongs to a specific building than if they're shared.

Miflin questioned how big of an issue the illicit dumping really would be. Shared containers have been the norm for cities that have done containerized collection for a long time, like Barcelona or Paris.

Closer to home in Hoboken, officials plan to pilot shared four-wheeled containers in the street for multi-family housing early next year following recommendations from its own trash overhaul plan — another example of that city showing its larger neighbor across the Hudson River how it's done.

Even DSNY's own initial test in West Harlem relied on bins split across several buildings, Miflin noted.

"Well how do they enforce illegal dumping now? Anybody can put illegal bags in the street. And was illegal dumping a problem in their pilot," she said.

The model of assigning a street bin to a specific building, basically a locked container, will actually an be an outlier, she said.

"I don’t know any other city in the world that just puts these containers in the street and has them for the exclusive use of the building. That’s a new model they’ve come up with," Miflin said. "It’s basically just private storage for a building."