Central Park could open cycling up to tens of thousands of student commutes to school if its lack of dedicated crosstown bike paths wasn’t getting in the way.

Biking to school is a life-changing transportation trick. It’s time-efficient, cost-effective, and a boon to the physical and mental health of both kids and parents. It’s also one of the most environmentally friendly ways to get around. As parents of bike-riding elementary and middle school students, our experience riding through Central Park with our kids can offer lessons in the obstacles and possibilities of making New York a safe bike-to-school city.

No data exists on how many children ride bicycles for transportation in New York City, an oversight that is part of a larger tendency to ignore children in transportation policy and planning. In general, we know more people than ever are riding bikes in the city, including parents transporting kids on cargo bikes and teens biking themselves to school. And the enthusiasm for bike buses shows that many more kids are ready to ride once a safe environment is provided.

The benefits of children biking to school are profound and multifaceted. Beyond the physical and mental health benefits, the act of a child navigating themselves a couple miles through their city under their own power fosters a sense of confidence and independence, opportunities that are often lacking for kids today. Research also shows that children who arrive at school by active means show up ready to learn and perform better academically. Children who regularly bike to school are more likely to bike throughout their life, meaning an investment in safe routes to school today will pay dividends well into the future.

But national data suggests that younger school-aged kids actually bike less than they did two decades ago, even as adults and older teens bike more. This unfortunate backwards trend in childhood autonomy is the product, among other factors, of a built environment that is hostile to kids, and made even more dangerous by distracted driving and car bloat. Altogether these factor exacerbate an overprotective parenting culture that keeps our kids locked into a cycle of depending on adults to get around.

What does this have to do with Central Park?

Central Park is a two-and-a-half mile-long, 843 acre, (mostly) car-free space in the heart of some of the densest neighborhoods in the United States. Nearly 120,000 school-age kids live within a mile of the park, and there are more than 200 schools within a half-mile of its boundaries.

Central Park could become an essential transportation infrastructure in the lives of thousands of school children and their neighbors. In fact, it already is — our families, and hundreds of others, rely on it for our daily school commutes despite decades of design and policy decisions that discourage and complicate using the park for transportation.

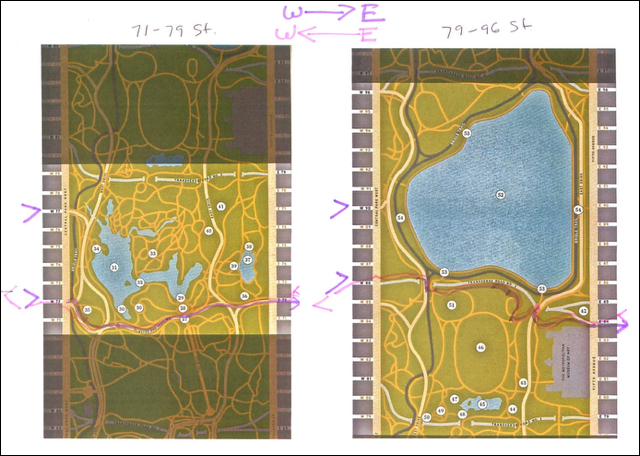

The main cycling infrastructure in Central Park is the loop (or “Drives”, as they’re still officially known), a 6.1-mile former carriageway (and, until relatively recently, a three-lane road for cars). The loop circumnavigates the park, through twists and turns and up and down hills, in a strictly counterclockwise direction for people riding bikes, making it ideal for recreational and sport cycling, but much less practical for anyone crossing the park for transportation. This is especially true for children, who can’t easily ride an extra mile or two out of their way, or casually climb an extra hill while trying to get to school on time.

Park rules prohibit bike riding on 99 percent of Central Park’spaved paths, with only a short, half-mile section near 97th Street officially shared with bike riders. This makes finding legal ways to get to and from the loop impractical to impossible, depending on where you're coming from and where you need to go. Even on the loop, one-way cycling traffic means riders are often forced to go a mile or more out of their way to find a legal place to exit the park.

This puts parents and kids biking to school through Central Park in a tough spot:

- We can do the convenient and rational thing and break the “no riding” rules for a short stretch, respectfully using forbidden paths, going slowly and deferring to pedestrians. (This good-faith effort often leads to scolding, and sometimes aggression, from fellow park goers.)

- We could attempt to avoid the park by riding alongside vehicles in the transverses or on adjacent streets that lack adequate bike infrastructure, a risk we’re simply not willing to take as parents of young cyclists.

- Or we could just decide not to ride, giving up on this remarkable transportation solution, with all the benefits and joy it brings, because the obstacles are too great.

It shouldn’t be this hard. Central Park could designate frequent, convenient cross-park paths tomorrow — creating predictability for all park users by knowing where to expect people on bikes and increasing safety for everyone while normalizing this beneficial mode of transportation. Plus, a bike-to-school friendly Central Park would perfectly align with the park’s commitment to environmental sustainability.

As far back as 2010, the Central Park Conservancy and Parks Department have acknowledged the need for cross-park paths and have even made a few modest changes. In 2020, both Community Board 7 and Community Board 8 voiced their support for a more comprehensive cross-park plan. But improvements have so far stopped short of providing full access, leaving the conditions functionally unchanged for thousands of riders a day, including kids and families trying to get to school.

An advocacy letter to kick off this school year, addressed to the Central Park Conservancy and NYC Parks Department, has already been signed by more than 170 parents, students, teachers, administrators, and allies from nearly 60 schools around Central Park, asking for legal crosstown routes into and through the park so kids can safely ride their bikes to school.

Kids commuting to school by bike should be something we all celebrate and support. The benefits are too important not to. Officials have an obligation to finish the work of cross-park paths in Central Park and demonstrate that when we make space for kids to safely bike to school, we make the city better for everyone.