I’ve said for years that there’s no smarter big-city public policy than congestion pricing and that New York is the place where congestion pricing can do the greatest good. Our combination of hellish traffic, excellent but underfunded transit to the central core, and commuters who place great value on driving guarantees it.

Lest that last attribute seem opaque, remember that the intent with congestion pricing is to deter only a fraction of car trips ― 15 to 20 percent ― into the congestion zone. Preserving the other 80 to 85 percent is how the MTA meets its billion-dollar-a-year revenue requirement under state law, a stream that will fund $15 billion in bonds to pay for subway signals, elevators and other vital transit enhancements.

“Don’t ban cars, bill them” for their congestion is the policy’s true mantra for New York. Hyper-congestion not just in the zone but also in the boroughs and counties that funnel traffic to it is so constant and debilitating that backing down from it even fractionally will spin off huge benefits.

EMERGENCY ACTION: Join us at 12pm today at Governor Hochul's office (633 3rd Ave) to make sure she knows the true political threat isn't charging suburban drivers to enter Manhattan, it's defunding transit improvements for millions of New Yorkers!https://t.co/Z81NZ2cQdk pic.twitter.com/5qMOwlGktV

— 🚇 Riders Alliance (@RidersAlliance) June 5, 2024

Squashing traffic delays, rather than caving to panicked drivers by delaying congestion pricing, is what Gov. Kathy Hochul and her team need to do. These congestion pricing pointers may help:

Congestion pricing isn’t fundamentally an environmental or air pollution program

A half-century of tailpipe engineering has done away with 95 percent or more of harmful car and even truck emissions.

Congestion pricing is a policy to help New York City and the region work better by letting residents and businesses avoid vast amounts of time and frustration lost in traffic and needlessly slow trains.

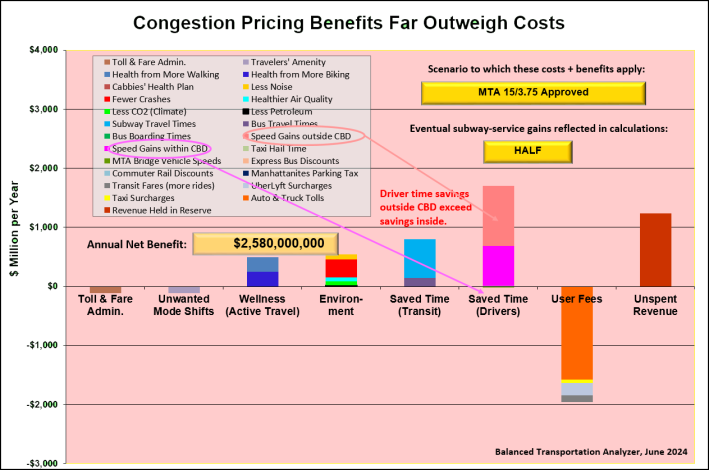

For every dollar’s worth of air-quality improvements, congestion pricing will bestow on city transit riders $12 and on the region’s drivers $25 in saved time.

A clear majority of the driver time savings will occur outside the congestion zone rather than inside

Congestion pricing will save millions of hours each year for drivers who aren’t even headed to or from Midtown and Lower Manhattan but whose highway lanes will become less jammed.

Congestion pricing is good for business

A surprisingly high share ― more than one-fifth ― of the car trips to the zone that the congestion fee will do away with aren’t landing in the Manhattan core, they’re going through, making congestion pricing’s damper on Manhattan commerce and other activity less than it appears to the uninitiated.

Indeed, with congestion pricing, an estimated 50,000 more people will travel to the congestion zone each day, thanks to better transit and a projected 9 percent uptick in car occupancy rates.

Truckers actually win big

The projected 12-percent gain in travel speeds inside the zone and 6-7 percent on routes to and from the zone will reward plumbers and electricians and produce-delivery drivers — and others in this essential sector of New York’s economy — with time savings worth more than the tolls.

Taxi drivers, too

The same applies to for-hire-vehicle drivers and passengers. Fewer traffic jams in the congestion zone will bring not just faster taxi and Uber trips but also fare reductions (due to less metered “wait time”) offsetting some of the hit from the new surcharges on FHV trips in the zone. My modeling projects a net 9-percent rise in yellow-cab trips, and 2 percent for Ubers and Lyfts.

These positive outcomes from the approved congestion pricing program have been obscured by motorist pearl-clutching (ironically, given the prospective time savings) and media coverage that miscasts congestion pricing as an environmental or climate idea. As I pointed out in this space in 2018, in the runup to the 2019 enabling legislation (Congestion Pricing Will Help Stop Climate Change — But Differently Than You Think), the main climate benefit lies in making inherently climate-friendly New York a more inviting and efficient place to work, visit and live relative to the distant suburbs or the Sun Belt.

If Gov. Hochul needs to signal flexibility by tempering the approved congestion fees, she can modify elements of the plan developed by the Traffic Mobility Review Board and approved by the MTA board late last year:

- Make the 5-6 a.m. and 8-9 p.m. weekday hours off-peak so that inbound drivers pay only $3.75 rather than the full $15.

- Roll back the $15 peak Saturday, Sunday and holiday tolls to $10.

- Extend the one-toll-per-day cap for car drivers to include truck drivers.

- Waive the added $1.25 surcharge for taxi trips touching the congestion zone (but keep the new $2.50 zone fee for Ubers and Lyfts).

Writing on deadline, I wasn’t able to input these changes into my BTA spreadsheet [downloadable 18 MB Excel file]. But I’m certain that this modified plan is robust enough to satisfy the billion-dollar-a-year revenue mandate with room to spare.

In my congestion pricing history essay in April for the Washington Spectator, Diary of a Transit Miracle, I complimented Kathy Hochul’s “resolute and enthusiastic support” for congestion pricing and called it “the decisive ingredient in shepherding congestion pricing to safety.” I also noted the difficulty that New Yorkers, even transit users, have “in connecting congestion tolls to improved travel and a better city.”

The governor’s apparent last-minute jitters suggest that she too isn’t immune to this difficulty. That’s distressing but understandable. After all, tackling jealously guarded entitlements ― in this case, the right to inconvenience others by usurping public space for one’s vehicle ― is, perhaps, the hardest thing an elected official can do.

“You know the darkest hour is always just before the dawn,” Crosby, Stills and Nash sang some 55 years ago. Gov. Hochul should stay the course and usher in the bright and brand-new day that congestion pricing promises.