"Law and Order" this ain't.

On Wednesday and Thursday, when congestion pricing foes from New Jersey meet boosters from the MTA and the federal government in a Newark courtroom, they won't be participating in a TV-style trial, but making their case to Senior Judge Leo Gordon to approve either side's motion for summary judgment, ending the dispute without a trial.

For the feds and the MTA, summary judgment means the case is dismissed. For New Jersey, summary judgment means that Gordon orders the MTA perform additional environmental review before implementing congestion pricing.

In actuality, Gordon, appointed to the federal Court of International Trade by George W. Bush in 2006, will be part judge, part lawyer and all jury: His job is to ask both sides questions about the administrative record of congestion pricing and decide whether the tens of thousands of pages of analysis compiled by the MTA meet the federal standards for a sufficient review.

"In a trial, [participants] are establishing facts through testimony and so forth," said Sean Malone, one of the attorneys who represented opponents of the widening of I-5 in Portland. "In an administrative record case, ... the court is reviewing a decision an agency made based on a record that was made with public comment."

So let's be clear: This two-day hearing is not about whether New York State is allowed to pass a law establishing congestion pricing, or even if congestion pricing itself is constitutional (New Jersey did try to slip that claim in to its filing earlier, but was rebuffed by the judge).

This hearing is solely about convincing Gordon, age 72, that the MTA dotted all the i's and crossed all the t's — or, from Jersey's perspective, convincing him that more i's and t's are needed.

To do so, Gordon will review the administrative record, which is a compilation of every communication and decision-making document that went into the federally mandated environmental assessment conducted by the MTA. That administrative record also includes records of communication between government agencies, public comments, studies that relate to the project and more.

In addition to looking at the administrative record, Gordon will be asking attorneys about it to determine whether the FHWA acted in an arbitrary or capricious manner when it granted a "Finding of No Significant Impact" to the congestion pricing environmental assessment. Environmental law experts previously told Streetsblog that even if New Jersey didn't like the outcome for the EA, the depth of the study should satisfy a federal judge that a full environmental impact statement is not needed.

"New Jersey makes all of these claims that DOT didn't do enough outreach to stakeholders in New Jersey, for example, or they didn't examine certain impacts to the depth that New Jersey would have liked," Amy Turner, the director of the Cities Climate Law Initiative and research scholar at Columbia Law School's Sabin Center for Climate Change Law told Streetsblog last year. "A lot of that can easily be pushed back on by looking at the level of depth that the environmental review did, in fact, go into — even though it was called an environmental assessment, rather than an environmental impact statement."

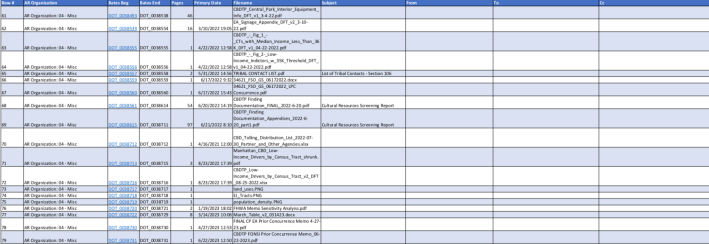

The congestion pricing environmental assessment is a 4,000-page document — and the record that went into creating and approving that study was a 47,000-page tome made up of 1,600 documents, according to an FHWA court filing.

That administrative record is so big, in fact, that the FHWA was exempted from having to file the entire thing online, and was instead able to file a record summarizing the entire thing. The summary is a 102-page PDF that lists, in date order, correspondences, studies and public comment on every burp and spit of congestion pricing.

The hearing will center only on that administrative record and nothing else. Lawyers for the Garden State and the MTA and Federal Highway Administration will answer questions over two days, and Gordon, a Jersey native, will make a ruling before June. Unless, of course, he sides with New Jersey and orders up a full EIS.

"The hearing doesn't resemble a trial, really, it's answering questions from the judge, clarifying anything, it's less formal than a trial," said Malone. "And it's really just typically one side presents their case, generally speaking, the other side will respond, and then there might be kind of a final rebuttal from the plaintiffs."

The action starts at 9:30 a.m. on Wednesday at U.S. District Court in Newark.