A proposal to restore train service to central Queens is in danger of running off the tracks.

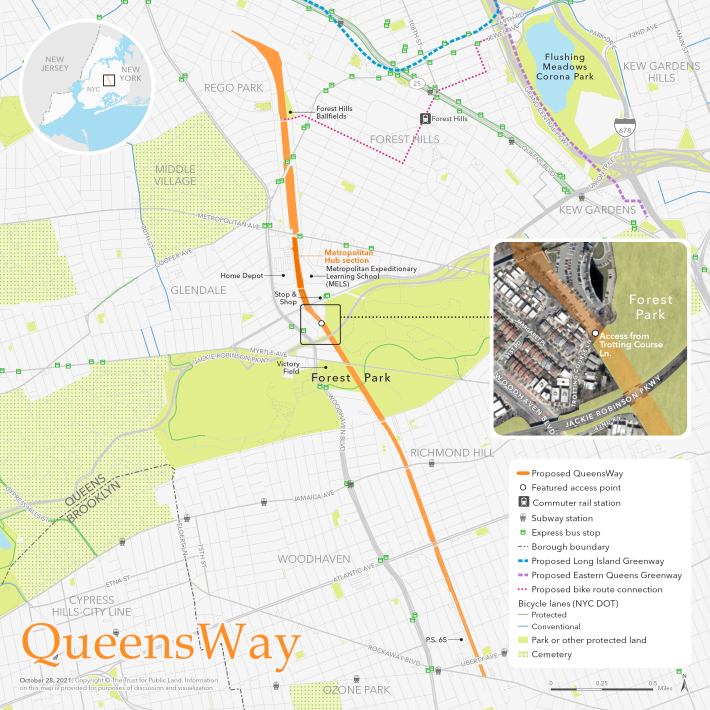

On Wednesday, federal authorities announced a $117-million Reconnecting Communities grant for the city to fund another piece of the QueensWay — a 3.5-mile linear park proposed for an abandoned Long Island Rail Road spur between Rego Park and Ozone Park.

The federal grant marks the second big-money infusion into the park proposal, following Mayor Adams's announcement in 2022 of $35 million for an environmental review and construction of first phase in a stretch between Metropolitan Avenue and Union Turnpike, known as the Metropolitan Hub.

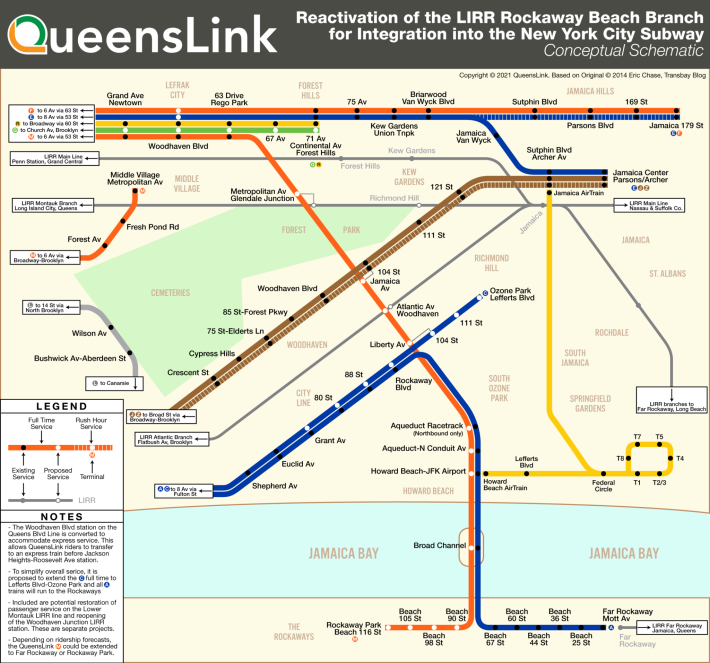

But a separate group of Queens residents has a different plan for the right of way: a subway extension dubbed "QueensLink" connecting Rego Park and Rockaway. That proposal also includes 33 acres of public green space and bike paths, which proponents say hits the sweet spot of both expanding transit and adding park space — a two-birds-one-stone solution not accomplished by QueensWay.

As such, QueensLink advocates say the city's rush to advance QueensWay annihilates the possibility of any rail project on the corridor.

"Its purpose is to derail the train," QueensLink Executive Director Rick Horan said about the federal grant. "They just want to get this thing started so that the train can never seriously be considered."

The Adams administration seems to favor the QueensWay park concept, but City Hall insists that both ideas remain feasible. After Adams approved $35 million for the Metropolitan Hub, spokesperson Charles Lutvak said, "The proposed Met Hub does not preclude an MTA project if [MTA officials] determine one is feasible, and we are ready to partner with them if they decide to move forward."

Deputy Mayor Meera Joshi echoed that message on Wednesday, refusing to declare the transit piece of the project dead and buried.

"It doesn't necessarily prohibit future investment in rail along the same line," Joshi told NY1. "Those two don't directly conflict. But just as transit is connection, parks are immense connections."

QueensLink supporters say it's technically true that building a park wouldn't prohibit reestablishing train service in the future. But if the park is fully built out, the MTA would have to rip it up to make a rail link, a politically unpalatable option once people start enjoying the Queens version of the High Line.

"The more they build, the more money they invest, the less likely it will be that anybody will want to rip up a brand new park to put transit in," said Horan.

It's unclear exactly what the design of the second phase will look like, but an illustration of the park indicates it will be built over the existing rail right of way:

QueensWay advocates are more circumspect about the possibility of rail, noting that the government would always have the right to reactivate the transit right of way.

"The QueensWay will not preclude rail," said Friends of the QueensWay spokesperson Karen Imas. "If government many years from now does want to fund and implement rail, they always have that right."

One of the legislative supporters of the QueensLink said that he's not giving up yet — and that he still believes in the prospects of the train and park happening together.

"What I've learned about government is that it ain't over till it's over," said state Sen. James Sanders Jr. (D-Queens), who pushed for the Senate to include $10 million in its one-house budget to fund an environmental impact statement on the QueensLink.

Sanders said he's hoping to get a meeting with U.S. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, who was instrumental in getting the grant for the QueensWay, and try to convince her of the case for the rail project.

"God willing, you're able to show them the incredible opportunity to maximize not just that one thing, but to have two beautiful, major things," he said.

The $152-million total investment in the QueensWay so far suggests the city favors the park plan as the more permanent solution. QueensLink supporters, on the other hand, have struggled to get funding or recognition of their idea, beyond the State Senate's EIS proposal this year.

QueensLink advocates have accused the MTA of sandbagging the project by releasing an $8.1-billion price tag. Supporters of the rail link say it could get done for $3.4-$3.7 billion.

The MTA has since reduced its cost projection to $5.7 billion, but predicted that it would only attract 2,000 new riders per day and wouldn't dramatically enhance an area already served by the public transit (Woodhaven Boulevard Select Bus Service, the recipient of nearly $260 million in federal money in recent years, runs parallel to the route). The MTA also noted that completing the QueensWay park would force MTA to "compete ... along this corridor."

The proposal to do both things at once has won the QueensLink support from an odd-fellow coalition that stretches from democratic socialist Assembly Member Zohran Mamdani to self-professed "common sense" conservative Council Member Bob Holden. But neither the MTA nor Gov. Hochul have shown any inclination to support the transit project, instead backing the reactivation of a different Brooklyn-Queens rail connection to create the Interborough Express.