Transit union leaders have come out against congestion pricing even though only a tiny sliver of their members would ever pay the toll — and even though the billions in revenue raised by the new fee will be spent on MTA improvements that benefit the workers.

Just 1,500 subway workers and 700 bus workers out of 40,000 total employees commute into the tolling zone — just 5.5 percent of the workforce, all of whom can ride transit for free, according to the MTA. And only a tiny fraction of those workers commute by car.

Nonetheless, TWU leaders criticize the MTA for “tolling our own workforce."

“Subway employees tend to start their day at subway yards, where we store trains, and there are no subway yards inside the congestion pricing zone," an MTA official told Streetsblog. "There are seven non-yard subway terminals where a very small relative handful of employees can originate."

"[Bus employees] work out of 36 shops and depots, mostly across the five boroughs, but there is also one in Yonkers. Of these 36 facilities depots, one, and only one, is located within the central business district tolling zone."

And it's not as if the vast majority of workers are driving; authority employees used their free transit passes to use subways or buses 19.4 million times in 2023, according to the MTA.

Meanwhile, money from the tolls that tens of thousands of non-MTA workers will pay would funnel around $3.2 billion into work that MTA union members will perform.

There's another irony: TWU members played a key role in the coalition that got congestion pricing passed in the state Legislature in 2019 only to turn against the tolls as their planned mid-June launch approaches. Union leaders cite the potential financial burden on their members among their criticisms.

“By tolling our own workforce — the essential workers who are the backbone of the city transit system — the MTA is essentially milking the cow before even it's fed,” TWU Local 100 President Richard Davis testified at the MTA's congestion pricing hearings last week.

Union leaders frame their broader argument against congestion pricing — voiced by Davis and TWU International President John Samuelsen — as a plea for more transit services. Their argument is misleading; the MTA already increased service on several subway lines last year.

Samuelsen has almost exclusively focused his call for more service on costly express buses — the region's least-efficient, most-subsidized transit mode. The MTA spent more than $11 per express bus rider in 2019, according to the Citizens Budget Commission — a higher subsidy the widely panned NYC Ferry.

Express bus ridership is still at 80 percent pre-pandemic levels, The New York Post reported last week — so those riders likely receive an even greater subsidy today.

It was a thrill to stand w/ @TWULocal100 in 2019 when they lit up a last-ditch anti-CP "rally" near the QBB, & an honor to parlay w/ @TwuSamuelsen as unpaid consultant to @NYGov's FixNYC CP panel in 2017-18. His/their last-minute oppo makes me sad more than angry. What happened? pic.twitter.com/EN39tiAbGv

— Charles Komanoff (@Komanoff) March 8, 2024

Davis, meanwhile, accused transit leaders of “rushing headlong into congestion pricing without considering the ramifications” and claimed the city doesn’t have “a comprehensive and reliable public transit system in place to accommodate increased ridership.”

The comments ignored the MTA’s record-setting on-time performance numbers, the fact that trains still sit relatively empty compared to pre-pandemic, and the MTA’s expectation that transit ridership will increase by just 2 percent as a result of the new tolls.

Davis also buried the work his own members did to turn around service since the 2017 “summer of hell” — for the sake of a relative handful of members who commute by car into Manhattan below 60th Street.

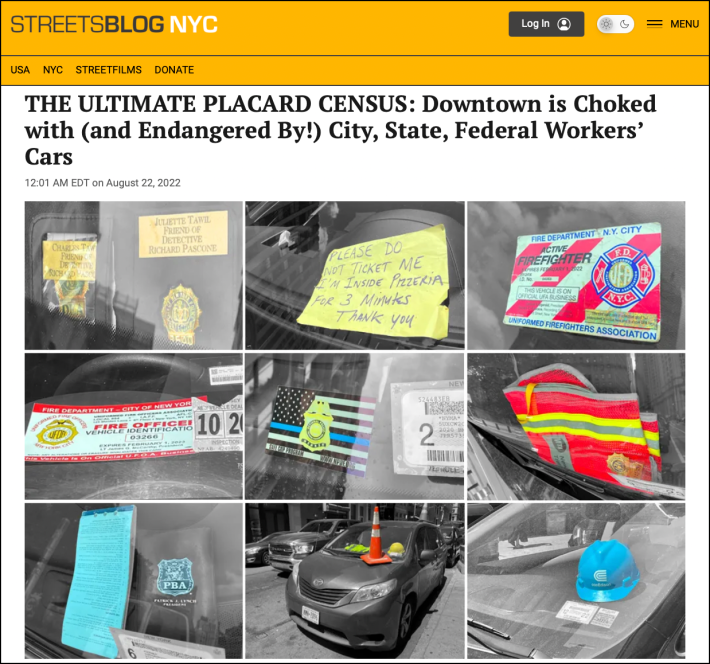

But TWU isn’t to blame for its members insatiable desire to drive into Manhattan for free. That responsibility falls on the MTA as well as Mayor Adams. The latter has done nothing to quell the city’s out-of-control parking placard culture. New York City Transit does not issue parking placards to its workers, according to an agency spokesman. That doesn't stop workers from using agency guidebooks, insignia and paraphernalia to get away with illegal parking.

A city- or state-issued parking permit or vest on the dash can be enough to make driving in and out of Manhattan’s busiest areas free-of-cost for the municipal workers who have them, Sarah Feinberg, former New York City Transit President and MTA board member, noted in an interview with Streetsblog. The result has been municipal workers — not only transit workers, but also firefighters, teachers and others — stomping their feet to oppose toll

“It's important to understand why some people are particularly upset about the prospect of paying $15. It is because we’ve been giving them parking placards, which in turns means free parking, often in illegal spaces,” Feinberg said.

"Unlike folks without placards, who must pay to park, driving into downtown has been free for them. For decades, we've made it very easy for them to drive into the most congested parts of the city. The reality is, without placards, congestion pricing might be unnecessary."