This project is generation-spanning.

The city’s nearly 15-years-delayed reconstruction of a critical bridge on the uptown portion of the Hudson River Greenway faces yet another setback — as the Department of Transportation pursues yet another design for the span that “better mitigates construction challenges,” the agency said.

Construction on the 80-foot Fort Washington Bridge, which crosses over Amtrak tracks near W. 180th Street, was supposed to begin this year, five years after Parks proposed a design — but with less than three weeks until 2024, DOT officials won't say when they plan to break ground.

The Parks Department, which owns the bridge, began work on the project in 2009 — meaning work on the tiny greenway span will now likely last longer than the time it took to erect the Brooklyn Bridge in the late 19th century. The existing bridge has significantly deteriorated, with heavy rains soaking the bridge so badly as to make it nearly impassible on some days.

"When there’s a thunderstorm, it just collects water, there is no drainage on that bridge. It’s Lake Amtrak in the summer," said Stanley O’Connor, a resident of the nearby micro-neighborhood Fort George, who founded a Facebook group focused on the uptown greenway. "I think nothing will happen until the bridge falls in."

Despite the decades-long need for a replacement, the decrepit overpass provides a vital link for thousands of cyclists and pedestrians who use the busy Hudson River Greenway’s northern Manhattan portion, one of the few safe routes to bike on that part of the island.

“It’s used by everyone, it’s not just some little thing that’s used by commuters or cyclists,” said Lucia Deng, an uptown and Bronx organizer with Transportation Alternatives.

“It’s wild to me that given the sheer amount of people that I’m sure use it, that it’s not a higher priority. It blows my mind.”

The city's initial timeline proposed to wrap up construction by 2015, but Parks didn't even have a draft design for the reconstruction span until mid-2018, according to reporting at the time by Patch.

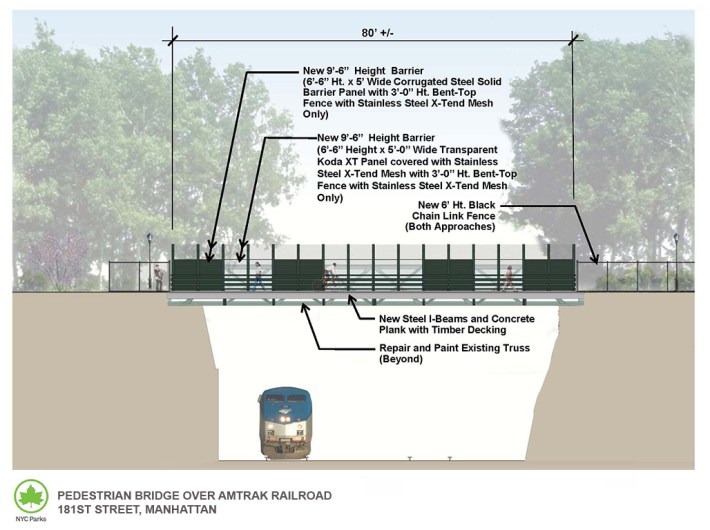

Proposed renovations back then included new steel beams, a concrete plank and timber decking — flanked by nine-foot barriers on the sides and a six-foot chain link fence on the approaches — for $5.9 million:

At some point after that, DOT took over the project. The latest round of design revisions will consider retaining access to the path and the adjacent park during the work, as well as passage of the railroad trains below, DOT spokeswoman Mona Bruno told Streetsblog.

Bruno referred to the old plans as a “preliminary design concept,” but declined to share more details — despite half a dozen follow-up requests by Streetsblog over the past week — such as why they decided to redo the designs, what the new schedule will be, or whether the cost will change.

The Parks Department did some emergency fixes to the bridge in 2018, amid complaints about holes in the wooden path so big you could see to the Amtrak tracks below. The agency even tried to close the link entirely that year — only reopening after Streetsblog exposed how the move cut off the crucial connector for thousands on the country's most popular bike lane and sent cyclists on a 23-block detour.

More recently, this summer, the city nailed down some loose planks after receiving an inquiry from Streetsblog about the bridge's condition.

“It’s just been this constant patchwork,” said Deng. “It just feels really haphazardly put together and not very stable.”

City and state government have mostly neglected the northern portions of the Hudson River Greenway, which receive less ridership and attention than more southern segments through glitzier nabes like the Upper West Side and Chelsea.

A few blocks to the north of the bridge, the greenway running on the shoulder of the Henry Hudson Parkway has been caving in for years, even after Parks tried to fix that section for more than a million dollars last year. The paths closed during that work and the agency sent cyclists on a dangerous detour through Washington Heights with little safe bike infrastructure.

The agency has done a poor job of managing its many greenways across the city, and advocates have called on DOT to take over their maintenance, since the latter agency has more resources to repave cracked paths.

The latest delays are just more proof that officials are in no rush to help uptowners, said O’Connor.

“It’s so non-committal,” he said. “Without a commitment, I think there’s no reason to hope that it would be done anytime soon — any year soon.”