Never mind the bollards...

The city has stopped carrying out the original goals of a much-hyped 2017 Council bill that sought the installation of safety barriers around 50 schools and 20 critical intersections every year — a proposal that had been drafted by the Council member who is (wait for it!) running the Department of Transportation right now.

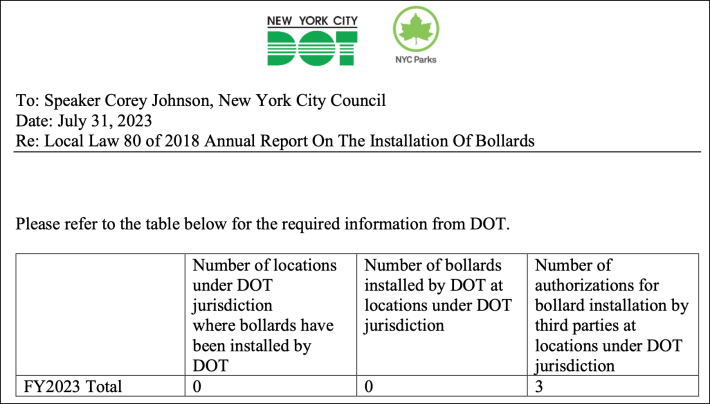

In annual reports, the DOT has told the City Council that it has not installed bollards at any location since at least July 1, 2020:

As drafted by then-Council Member Ydanis Rodriguez in 2017, Intro 1658 required the DOT to "annually install bollards on sidewalks immediately adjacent to no fewer than 50 schools ... to reasonably prevent a motor vehicle from passing through them and onto the sidewalk."

The bill also demanded that the DOT commissioner — reminder: that's now Rodriguez — install bollards "surrounding all pedestrian plazas [and] along no fewer than 20 priority intersections [per year]."

Again the goal of the bill — which passed when memories of the 2017 terror attack on the Hudson River Greenway and a similar vehicular attack earlier that year in Times Square were still fresh — was to "prevent a motor vehicle from passing ... onto the sidewalk."

In an interview back then, Rodriguez said the city "cannot wait for another terrorist attack when a vehicle is used as a weapon of mass destruction. The only tool that we have in our hands are pedestrian bollards." (At the time, the DOT that Rodriguez now runs opposed the bill, claiming it would deny the agency the flexibility of "selecting the right designs, treatments, and features based on the context of each location.")

DOT's argument was persuasive. By the time the bill passed in late 2017, then-Council Speaker Corey Johnson and the de Blasio administration had watered it down to merely this simple requirement: "Every year, the commissioner shall submit to the Council an annual report on the installation of bollards in the city."

Gone was the mandate to actually install the life-saving bollards.

The DOT and Parks Department have filed the annual reports religiously — and every year since the fiscal year 2020 report, it's been one big goose egg in both required categories: "Number of locations under DOT jurisdiction where bollards have been installed by DOT" and "Number of bollards installed by DOT at locations under DOT jurisdiction."

(As an aside, it's not clear if the DOT is taking the reporting requirement seriously — the reports it filed dated July 31, 2022 and July 31, 2023 are address to "Speaker Corey Johnson, New York City Council," when, in fact, Adrienne Adams was speaker on both those dates.)

So what happened? Obviously, the DOT installs bollards — it claims to do an average of 40 per year at street improvement projects all over the city. The failure of the DOT to document its bollard installation in the required reports seems to stem from lack of follow-up by the Council and an interpretation of the law by the DOT that it need only inform the Council of bollards it installs "as a member of Security Infrastructure Working Group." The group has not installed bollards since July 2020, but "is in the process to identifying and installing the next round of locations in partnership with NYPD."

"The reports you sited for your article only reflect specific bollards installed under the working group," said agency spokesman Vin Barone.

"This agency and others have installed hundreds of additional bollards in that timeframe that are not reflected in the report, with many installed for recent capital projects or in-house street redesigns. For instance, DDC installed 120 bollards as part of the Grand Concourse Phase 4 Great Streets project, which we cut the ribbon on today. And through in-house street redesigns, we’ve installed roughly an average of 40 bollards per year."

The Council legislation — which became law under then-Mayor Bill de Blasio — did not specify anything about a "working group." It merely required DOT to report "the total number of locations under the jurisdiction of the department where bollards have been installed by the department and the total number of such bollards installed."

The reporting debacle speaks to the need for reform of how city agencies' performance can be judged. Currently, the Department of Transportation is required by city law to report to the Council its performance in more than 50 separate areas (listed here). On many of those reporting requirements, the DOT does a good job — for example, filing complete and timely reports for such requirements as crashes caused by bicycle riders, the success of red light cameras, and its East Bronx scooter-share program.

But on other legal requirements, the DOT is a bad actor. Its report on bridge conditions is late, its report on the success of the Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program is late, it's school bus route reform report is late.

The DOT has also failed to put out its required "Interagency Road Safety Plan" since 2011. And it apparently never submitted a report on the environmental impact of diesel ferries. And its report on safety improvements near schools is incomplete.

Still, the Council often includes a reporting requirement in bills it passes, though it is unclear if anyone at the Council is actually reading the reports.