Everyone in the livable streets movement wants congestion pricing to start on schedule in May. But the many brilliant minds in the movement often have different approaches to reducing the political tensions that a new toll creates. After Streetsblog published an article about congestion pricing credits for drivers who enter the central business district via already-tolled tunnel, leading expert Charles Komanoff took us to task. But then, Hells Kitchen activist (and Open Plans board member) Christine Berthet wrote to tell us that Komanoff is missing something. Now, Komanoff wants to further explain himself, and we are more than happy to oblige.

The Editors

Here’s a congestion pricing position with few dissenters: If the MTA ends up charging a full congestion toll to drivers who use the already-tolled tunnels into Manhattan, the agency will perpetuate toll shopping. Why? Because such "double-tolling" will leave in place the long-standing toll differential between the authority’s East River tunnels and New York City’s East River bridges.

I’ve quantified the toll-shopping impact from double-tolling one of the tunnels, the Queens-Midtown. It’s not minor. Adding a congestion fee on top of the MTA’s existing Midtown Tunnel toll will cause 8,000 inbound vehicle trips a day to divert onto local streets in Long Island City to access the cheaper Queensboro Bridge.

But that won't happen if the current, nearly $7 inbound QMT toll is applied to the congestion fee. In that case, those 8,000 drivers will no longer be motivated to bail from the Long Island Expressway onto local streets but will instead shoot straight into Manhattan via the Midtown Tunnel. That simple credit will spare Queens residents and businesses from more of the deleterious effects of car and truck traffic while also lowering regional emissions by eliminating surplus miles driven.

Modeling congestion pricing’s potential to cut toll shopping

The concept is simple. The MTA tunnel toll hike last week pushed the each-way charge on its tunnels and major bridges to $6.94, or $7 rounded. The East River bridges, of course, are free. The $7 toll difference motivates many Midtown-bound drivers to trade time for money by taking the slower-but-toll-free Queensboro Bridge rather than the Midtown Tunnel.

With congestion pricing in the wings, the question becomes the extent to which eliminating that $7 difference will motivate those toll-shoppers to start using the tunnel instead of the bridge.

First, it's worth noting that that the combined 80,000 daily vehicles that currently squeeze into East Midtown are split roughly 55 percent via the Queens Midtown Tunnel and 45 percent using the Queensboro Bridge. (While the Queensboro carries more cars and trucks than the Queens-Midtown, much of its volume is vehicles that exit the bridge via the 62nd Street “flyover” and thus don’t directly enter the congestion zone; those that subsequently proceed south are counted in official statistics as entering the zone via 60nd Street.)

I chose a representative car trip from Rego Park to Rockefeller Center using both routes (the choice of starting and ending points isn’t crucial to the outcome since the analysis looks for changes to today’s equilibrium rather than absolute figures).

I then specified the total cost for each route: gas, parking, tolls and, most important, time, set at $50 an hour (a figure that reflects the relatively high incomes of car commuters to the Manhattan core; before critics object, consider that a lower figure would strengthen the toll shopping impact).

My assumptions, including my segmentation of trip distances and speeds between Manhattan and Queens, may be seen in the new Toll Shopping tab of my Balanced Transportation Analyzer spreadsheet (18 MB Excel file). The calculated costs today are $55.99 for the tunnel route and $62.27 for the bridge route, making the tunnel $6.28 less expensive, on average, than the bridge.

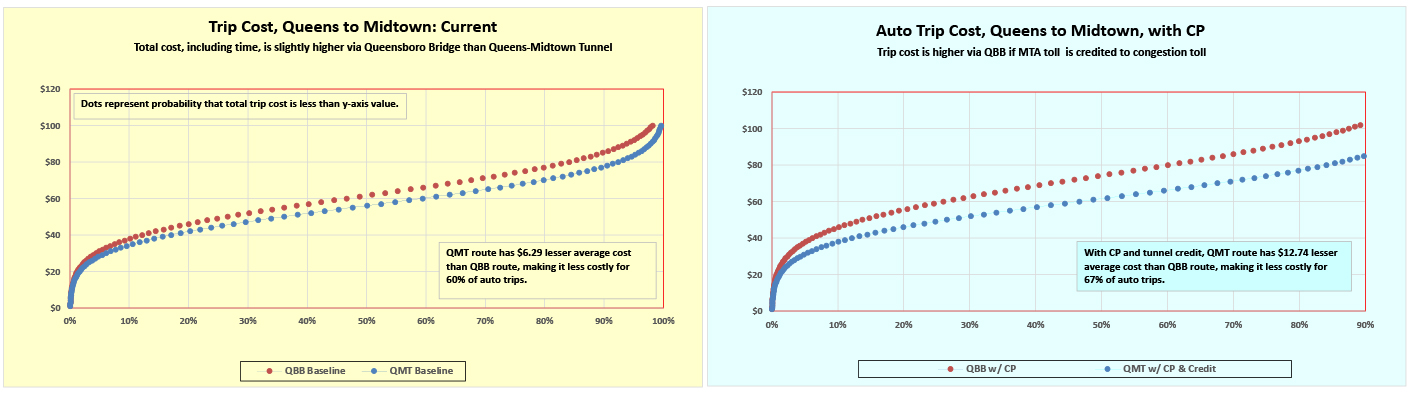

Of course, not every Queens-to-Midtown traveler takes the cheaper tunnel route because each average reflects a broad distribution of travelers holding a variety of preferences and experiencing a range of costs. To capture this travel diversity, I developed probability distributions around the respective “point” estimates of trip costs. These distributions indicate that the tunnel route beats out the bridge route for 60 percent of travelers, as shown in the left of the two graphs below. (Note that the 60 percent calculation is close to the 55 percent estimated actual share of Queens-to-Midtown travelers who take the tunnel.)

I then repeated the calculations with congestion pricing. What changes are the travel speeds and, thus, time costs for both borough segments, the fuel costs (since congestion pricing will cut down on stop-and-go driving, raising fuel economy), and, most important, the addition of the new congestion toll to both the Midtown Tunnel and Queensboro Bridge routes.

If, as the Congestion Pricing Now coalition, Gridlock Sam Schwartz and I all urge, the existing $6.94 inbound Queens-Midtown Tunnel toll is deducted from the new congestion toll, the mean difference between the respective routes’ cost more than doubles, to $12.74, from $6.28 today. The result, shown in the blue graph above, is that with congestion pricing, the tunnel route will be drivers’ choice for 67 percent of Queens-to-Midtown vehicle trips. That’s a rise of 7 percentage points from the current 60 percent of trips for which the tunnel is cheaper.

Translation: fewer toll-shopped trips

With an estimated 80,000 vehicles a day driven from Queens to Midtown via the tunnel and bridge combined, a shift of 7 percent calculates to around 5,500 fewer toll-shopping trips into Midtown via the bridge each day ― provided the current tunnel toll is credited to the congestion toll.

If it isn’t ― if inbound drivers using the Queens-Midtown Tunnel are made to pay a $15 peak congestion fee in addition to the standing $6.94 MTA toll ― not only do we lose the possibility of eliminating 5,500 toll-shopped trips, we’re likely to add another 2,500 trips diverting from the tunnel to the bridge, according to my modeling. That’s because congestion pricing, by thinning traffic volumes and boosting travel speeds, reduces travel times more for the longer bridge route. (Here, it helps to keep in mind that toll shopping means longer-distance trips, by definition.)

To sum up: the choice between crediting or not crediting the existing Midtown Tunnel toll isn’t about toll fairness. It’s a choice between eliminating 5,500 toll-shopping vehicle trips a day vs. adding 2,500 ― a swing of 8,000 toll-shopping trips.

A similar choice for the MTA’s Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, which for decades has been losing vehicle trips to the untolled Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges, has separate, additional implications for toll shopping.

Considerable emissions, gridlock and danger to local pedestrians and cyclists are implicated in whether congestion pricing includes tunnel toll credits. So are MTA revenues available to support transit operations, since, by statute, most MTA surplus bridge and tunnel toll revenues are allocated to NYC Transit and the authority’s two commuter railroads. I hope to quantify those impacts in a future post.