New York’s bike infrastructure is deeply fractured, and leaves a laundry list of neighborhoods with inconsistent lanes. A proposal for crosstown bike paths on the Upper West and East sides has potential to close that gap — but should go further by significantly reducing the presence of cars on the arterial transverses cutting across Central Park.

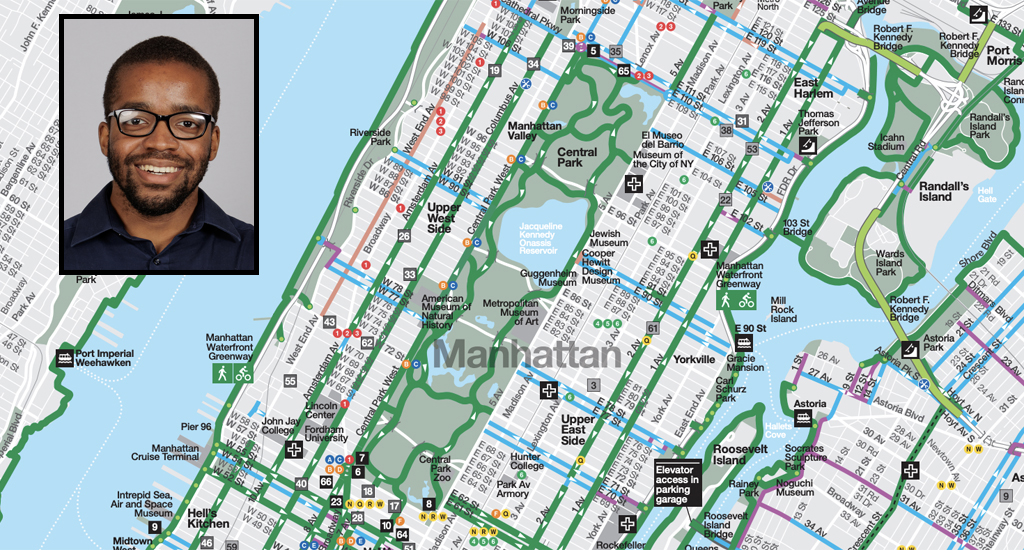

Aside from East 61st Street and East 62nd Street, there are zero east-west protected lanes between 55th and 158th streets. There are some unprotected lanes (arguably more dangerous than having no lanes), but those are far between.

In the densest neighborhoods in America, cyclists must contend with drivers who often have no regard for their presence or safety. It was only a matter of time before this lackluster infrastructure would claim a life — and in July, a truck driver killed 28-year-old cyclist Carling Mott on E. 85th Street. A past Department of Transportation attempted, in 2018, to install a protected bike lane there but was thwarted by opposition from politically connected, self-interested folks in the area. Nearly a year after Mott’s death, calls to improve safety have yet to produce results.

The West Side’s Community Board 7 and East Side’s Community Board 8 both asked DOT to “study” installing protected lanes for cyclists every 10 blocks between 60th and 110th streets — but even that proposal is inadequate.

Consider that roughly 70 percent of Upper West Side households do not have access to a car and 85 percent of commuters on the Upper East Side were car-free in 2019. Few places are more appropriate for street redesign that accommodates car-free trips. West Sider residents and commuters itch for better infrastructure for non-car transportation as well. Over 80 percent of respondents find the existing network to be “just okay” or “not very good,” according to a recent survey by Streetopia UWS.

Just 15 percent of people who use bikes or other micromobility in the neighborhood feel extremely confident riding in the area’s existing, subpar bike infrastructure, the survey found. A neighborhood that clamors this much for safe spaces to bike needs more than one protected lane every ten blocks — and should do more than protect cyclists. Concrete should line these bike lanes to protect cyclists and provide extra room for pedestrians, and bus lanes should also be installed.

Another critical omission from the community boards resolutions was a means for bikes to get through Central Park, something advocates have been fighting for for decades. Increased crosstown ridership in recent years has made the need for this fix more urgent. Right now, the only safe and direct way for bikes to get across Central Park is on 72nd Street. Otherwise, the other choices are to take the hilly, time-consuming route around the loop, or to navigate the speeding cars on the other transverses, and the latter option has proven deadly. A proper, safe crosstown bike lane plan would include a vision for the transverses.

Proposals for shared paths through the park have been thrown around for years, but have amounted to smoke. Former Council Member Helen Rosenthal suggested making transverses one-way for cars and trucks, but that is not an adequate solution. Not only would that not give bikes proper space on the thoroughfare, but it would also sabotage the crosstown buses that use the transverses and regularly get stuck in traffic on them. So, like a vision for complete crosstown streets on the Upper West and East Sides, a proposal to accommodate proper crosstown travel should be just as ambitious — and ban cars altogether on select transverses.

Any of the cross-park streets — which run through highway-like underpasses — could become car-free. The routes primarily serve buses and connected direct like landmarks primarily used by pedestrians and cyclists.

Similar parks in other cities have fewer points for cars to them cross: Golden Gate Park in San Francisco has only two routes across the park for cars and is almost a mile wider than Central Park, which has four (not to mention the city has actively removed cars on the East-West roads in the park as well.) And the same logic that applied to decreased vehicle presence along the busways on 14th Street (and with this plan) would apply in Central Park: Increased reliability and speed of bus and bike travel within the park would take cars off the road, and both sides of Central Park would be connected, regardless of travel means. Everyone wins.

As we inch closer to a protected bike lanes on 60th, 70th, 80th, 90th, 100th, and 110th Streets, we should reach for the stars. Whenever we can get more people on bikes and transit, we must, and there is an opportunity to do just that. Fill part of Upper Manhattan’s depleted bike network and connect it with added benefits for ailing buses. That is a vision worth pursuing. And with a city with a lackluster reputation for bike and bus lane implementation, more ambitious demands are warranted, so let's give them those more ambitious demands.

Austin Celestin is a rising senior at New York University.