New York’s plague of cars endures, yet the proven vaccine gathers dust.

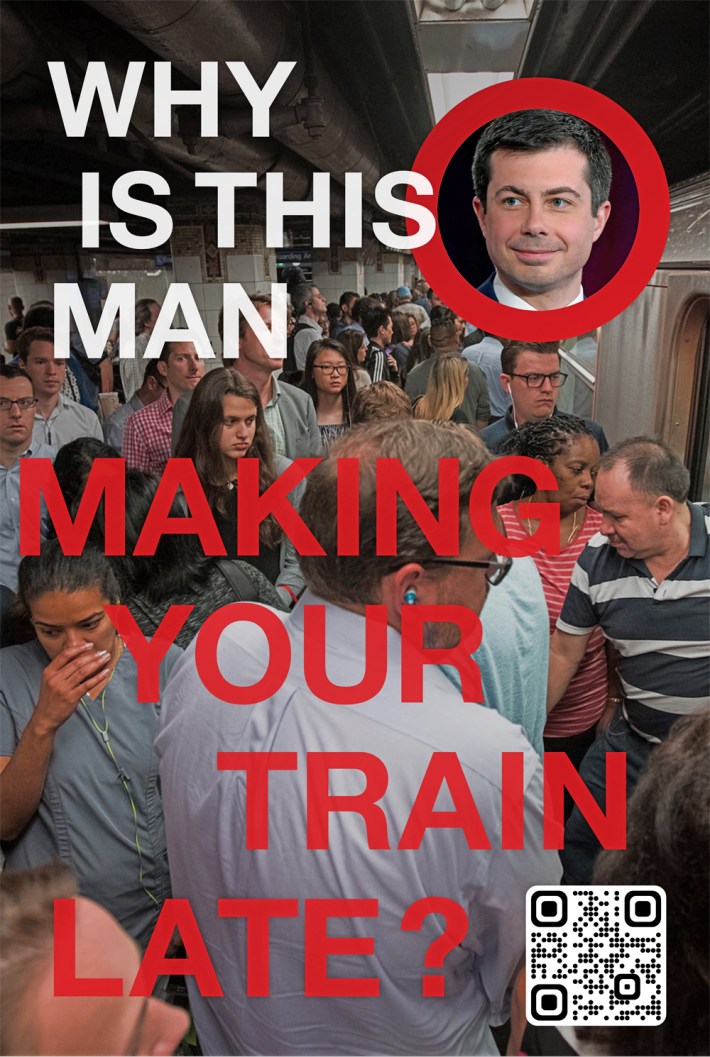

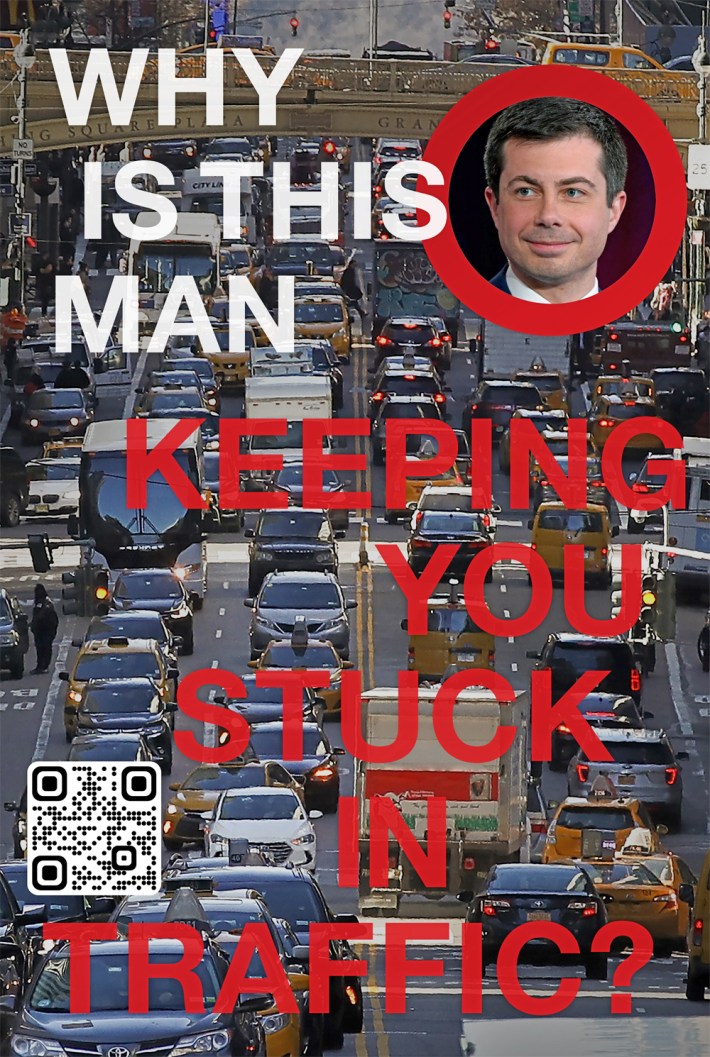

As Streetsblog readers know, congestion pricing — which passed the state legislature on March 31, 2019, was stalled by the Trump administration and revived under President Biden — is still in a holding pattern, thanks to the Federal Highway Administration’s dawdling review of the 46-volume environmental assessment that the MTA submitted last year.

Earlier this month, U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said the agency is “still neck-deep” in its review and [has] “no news to share on a timeline for approval.”

No timeline, no news. And with congestion pricing frozen, opponents who lost four years ago are again emboldened to take potshots at a policy that even some supporters are keeping at arm’s length.

So even though congestion pricing will be a balm for the city and beneficial even for most of the drivers who resist it, perhaps it’s time for an easy layup to jumpstart the conversation: let’s give every household in the 12-county MTA region a single untolled trip per month into the congestion zone.

Why would we do that?

It’s galling that supporters of congestion pricing — who have the moral and political high ground — would yield anything to drivers whining, “I shouldn’t have to pay” to drive to Manhattan to celebrate a wedding anniversary, consult with a doctor, visit a grandchild, attend a Broadway show or do any of the things that, apparently, one must have a car to do.

None of the arguments in favor of congestion pricing — that car trips slow down truckers, bus riders, EMS, other drivers; that central business district tolling will actually improve travel for the remaining drivers; that the $15 billion raised through congestion pricing will provide secure funding for vital transit improvements; that fewer cars will mean fewer road deaths and pollution; etc — dislodge the diehards.

But that’s where my one-freebie-per-month gambit comes in. It’s a bid to soften the opponents. To make them feel heard. And, in fact, to actually hear them. After all, some of the most vehement opposition to congestion pricing comes not from daily car commuters, but from occasional drivers to Manhattan whose objection isn’t just the dollars, it’s what the toll signifies: freedoms curtailed, horizons limited, their sense of fairness attacked.

The germ

The origin of the monthly freebie idea is an episode from the last century involving “directory assistance” calls. Anyone younger than a Boomer won’t remember it, but once upon a time, “operators” working for the “phone company” used to dispense, at no charge, telephone numbers of area businesses and households.

Over time, though, 411 calls were increasingly placed by a relative handful of customers. Eventually, the New York Public Service Commission authorized NY Telephone (Verizon’s predecessor) to charge 10 cents per call. Outrage ensued.

To the rescue came the famously plain-speaking PSC chair Alfred E. Kahn, who ordered NY Telephone to give customers a 30-cent credit each month stemming from the savings the company was getting from fielding fewer 411 calls — and Kahn then branded that credit as three free 411 calls per month. The outrage dissipated. What assuaged the public wasn’t just the monetary savings, it was that they felt heard.

The numbers

A once-a-month free trip into the congestion zone would cut annual net congestion pricing revenues by $110 million, according to my modeling. That hit, around 11 percent, is substantial, but it could be a worthwhile giveback if it helped seal the deal.

The loss to the region would be slight. Under my modeling, average speeds through the congestion zone would still increase by 17.8 percent with the once-a-month freebie, instead of 18.6 percent without it. The overall societal benefit of congestion pricing’s toll and reduced congestion would still be well above $4 billion per year.

Making up lost revenue

The 2019 legislation required that congestion pricing generate sufficient revenue to support $15 billion in transit capital investment, a mandate that is generally agreed to equate to a net take of $1 billion a year. If we give a once-a-month freebie, the congestion toll revenue falls below that threshold.

But that lost revenue could be clawed back by upping the toll structure from the assumed $5-10-15 offpeak-shoulder-peak rates to $6-$12-$16, a trade-off benefiting the occasional CBD driver at the expense of the regular commuter. It remains to be seen if such a move would be considered policy pickpocketing — a form of robbing Peter Motorist to pay Paul Motorist — or simply a necessary accoutrement to an imaginative policy twist.

Why bring this up now?

Congestion pricing discourse is, frankly, banal. Everything in its favor has long ago been said: Generates revenue to improve transit? Check. Cuts down on soul-killing, time-robbing traffic delays? Check. Encourages cycling and walking, makes city streets quieter, safer and livelier at the same time? Check, check, check.

If anything, the conversation has deteriorated since the MTA issued its environmental assessment last August. Advocates have had to ward off worrisome predictions of worsened traffic in underserved and overburdened communities — findings that are largely artifacts of inept modeling, as I noted at the time, or of labored assumptions (e.g., that the Lincoln Tunnel will be tolled without crediting the long-standing Port Authority toll), or both.

My once-a-month freebie seeks to not only change the discussion but also hoist some of the opponents on their own petard. If their objection to congestion pricing is genuinely rooted in the precious one-offs they harp on, this proposition should prompt them to reconsider.

If they do, there could be the makings of a deal. If they don’t, we’ll at least have regained the high ground.

Charles Komanoff is an expert on congestion and the head of the Carbon Tax Center. His opinions are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Streetsblog Editorial Board.