New York State has been underfunding the MTA by hundreds of millions of dollars for decades, quietly regifting dedicated taxes as its own legally obligated contribution to the transit agency’s operating budget.

Under a transit funding law established in 1975 known as 18-b, New York State agreed to directly fund the operating budget of state public transit systems, including the MTA, with matching funds from local governments every year. In the case of New York City, it means that city taxpayers give more than $150 million annual towards funding New York City Transit. Additionally, taxpayers living in counties served by the Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North also give the agency tens of millions of dollars from those counties’ general funds. The money from state and local governments is supposed to come from those governments’ general funds.

But for almost 30 years, New York State has shortchanged the MTA by reclassifying existing regional taxes already earmarked for the agency as money that the state is providing on its own. New York State has spent decades calling these dedicated taxes the state’s contribution from the general fund, even as every other county has held up its side of the bargain with a full contribution from its general fund.

The end result is that every year, the MTA is getting stiffed, with the amount rising to a shortfall of over $180 million per year since 2015.

The state’s process for skimping the MTA is hidden in the cosmic gumbo that is the appropriations process during the budget, and the way that dedicated taxes flow from cities and counties to the state. Despite the fact that the 12 counties served by the MTA pay specialized regional taxes that fund the Mass Metropolitan Transit Operating Assistance fund (MMTOA), those taxes such as the petroleum business tax or regional sales tax surcharge don’t immediately get earmarked for transit. Instead, they gets lumped in with every other dollar that goes into the state’s general fund.

From there, the MMTOA taxes are appropriated to the MTA in the course of the normal budget process. But for decades now Albany leaders have agreed that up to 90 percent of the state’s share of its 18-b contribution can just be a slice of the MMTOA taxes that need to be appropriated to the MTA anyway. The state then calls that money a contribution from the general fund, despite the fact that this money is coming from dedicated MTA taxes.

State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli dates the annual 18-b shortchange back to 1995, when the state pinched $128 million of MMTOA money. By 2008, the raids had become enough of an issue that DiNapoli’s “Financial Outlook For the MTA Report” explicitly called the practice a raid (in so many words).

“As we have pointed out in the past, the state has used a portion of these resources (since 1995) to fund up to 90 percent of its statutory obligation to subsidize the MTA’s operating budget, rather than using General Fund revenues as originally intended,” DiNapoli wrote. “Consequently, the MTA has been shortchanged by $2.2 billion since 1995, and will lose out on $709 million during calendar years 2009 through 2012.”

That was the projection of 10 years ago. By now, the amount of state money owed to the MTA is an astounding $4.9 billion. Although the money is a relatively small amount of the total budget every year, the point remains that the 18-b law is not set up to allow the state to slap its name on already dedicated funding.

“This is not the spirit of the law,” said Rahul Jain, the state’s deputy comptroller for the city. “The point was that local governments need to put in half, the state will put in half, and that is separate from what MMTOA is supposed to represent. It’s correct to treat them as two separate things.”

Representatives for the MTA declined to comment on the raids. However, the agency has not been shy about noting the chicanery if it can do so buried safely inside financial disclosures that only nerds read.

“An additional $175 million of MMTOA is annually earmarked to fund the State’s 18-b obligation to the MTA, which includes $154 million for NYCT/SIR and $21 million for the Commuter Railroads,” said the MTA’s Proposed Budget for 2023. “These funds are appropriated by the state, and there is a required local 18-b match from New York City and the counties [in the service area].”

And in a footnote in the budget document, the agency wrote “State 18-b Operating Assistance is a statewide mass transportation program that provides direct state aid to the MTA, which is appropriated by the State Legislature on an annual basis. Since 1994, the state has funded most of its 18-b payments with MMTOA.”

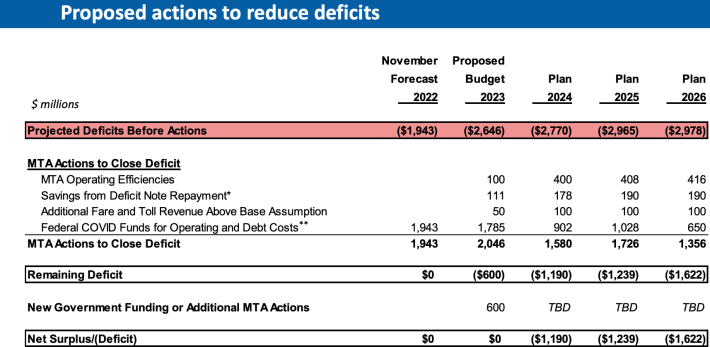

The material of impacts of the raids have been hard to quantify every single year, but the MTA’s own budget presentation shows that the yearly raids could cover the higher-than-initially proposed fare hikes over the next few years. The MTA has said it could raise $50 million in 2023 and $100 million from 2024 through 2026 if it raises fares 5.5 percent instead of 4 percent. That amount of money is more than covered every year by the state’s decision to provide its “matching” funds for transit out of dedicated taxes that already are earmarked for the MTA.

Transparency advocates say that the increasingly dire fiscal circumstances for the budgets of transit agencies around the state means that this is not a time to play shell games with transit funding.

“Transit systems across New York State are in danger of collapsing once federal [Covid] funding runs out, so the state must finally deliver on its funding obligations to transit riders by no longer raiding dedicated funds and restoring its full 18-b general fund contribution,” said Reinvent Albany Senior Policy Advisor Rachael Fauss. “Ending the budget gimmicks won’t be enough, however, so the governor must also create new dedicated funds to support the long-term needs of transit agencies.”

It’s yet to be seen whether the practice will finally end in 2023. A spokesperson for Gov. Hochul declined to say whether the governor will end the practice of raiding the MMTOA funds, and instead pointed to the 11.8-percent increase in state aid to the MTA that was in this past year’s budget, an increase that was due to dedicated taxes coming in higher than they had during the years when the pandemic’s economic crunch wrecked state tax receipts, not from making the MTA whole on what it’s owed.

One high-ranking member of the Assembly sounded ready to stop the steal.

“I wasn’t around 30 years ago to know the original intent of 18-b,” said Assembly Member Amy Paulin, the chair of the Corporations Committee. “Regardless, we don’t have to justify funding the MTA adequately. It is very justified.”