Pricing has power. Changes in the prices of goods and services affect demand for those items. For some products by a lot, in other cases not so much. And most impacts from price changes take time to unfold fully. But price-elasticities are never zero.

(Price-elasticity: The percentage change in consumption of something, relative to the percentage change in its price.)

That’s my take — and a touchstone of my work for carbon taxing and congestion pricing. Nevertheless, stories appear from time to time, claiming that sky-high gasoline prices aren’t affecting gasoline consumption. Streetsblog ran two such posts in just the past week: Why Americans Don’t Drive Less When Gas Prices Soar, last Tuesday; and, a few days later, New Yorkers Are Still Driving Like Crazy. (The latter was given more context in Monday’s headlines post.)

To be sure, those stories addressed the supposed stickiness in the amount of driving, which isn’t quite identical to stickiness in consumption of gasoline. Still, the messaging was clear: driving is so baked in to Americans’ psyches and living conditions that costlier gas can never make much of a dent.

Except that it is — at least in New York State. Following the lead of Streetsblog’s Still Driving Like Crazy post, I took a look at monthly statewide “motor fuel” tax receipts — levies on gasoline and diesel fuel burned in cars and trucks (boats also consume a small fraction) — from this May back to the start of 2019, the last pre-pandemic year. Since the per-gallon tax rate was unchanged over this period, changes in fuel use should be perfectly reflected in changes in tax collections.

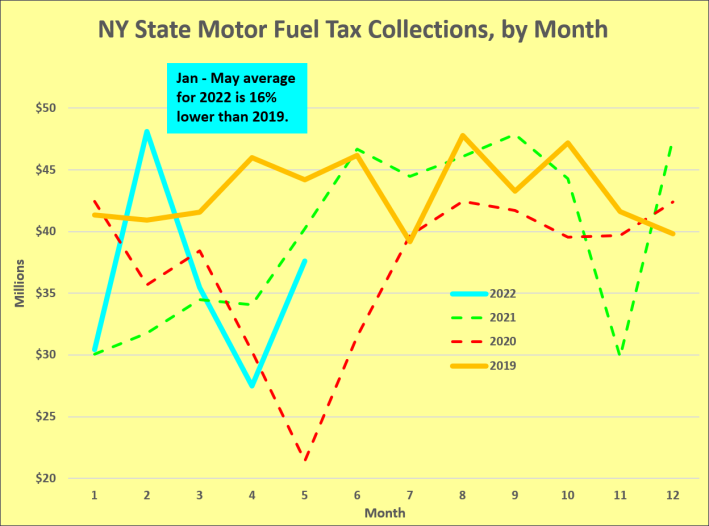

First, the chart:

From January through May 2019, the state took in $214 million in motor fuel taxes. Over the same five months this year, the take was $179 million — a $35-million, or 16-percent, drop.

To be honest, I’m not entirely sold on the precise figures. For one thing, this year’s February tax receipts figure of $48 million is crazy high — the biggest monthly take in five years. Though the anomaly is in the wrong direction (it pushes the 2022 total up rather than down), it doesn’t inspire confidence. Even more stark is the 40-percent drop comparing April 2022 vs. April 2019.

Moreover, the bottom-line result of a one-sixth fall in sales of gasoline and diesel this year compared to last is a lot higher than I would expect, based on my sense of gasoline’s short-term price elasticity. It’s also true that changes in the last several years in the economy and the very structure of society could muddy the impact of price changes. The increased penetration of electric vehicles might have knocked a percent or two off of gasoline sales.

Clearly, more analysis is needed, including from the other 49 states. Extrapolating from my figures for New York should be done cautiously, as the beginning, not the end, of a conversation on demand responsiveness to expensive gasoline. Still, in my view, the data here put the onus on price-elasticity skeptics to make a convincing case, if they can, that gasoline use in the U.S. is impervious to changes in its price.

[Editor's note: Our coverage of driving in the pages of Streetsblog focuses on the simple fact that Americans do far too much of it, the result of bad planning that promotes car dependency.]

Advertisement: Used Dutch Bikes is your one-stop-shop for authentic Dutch bicycles. Choose from classic “grandma bikes” to modern seven-speeds that can haul three kids without breaking a sweat. We carry authentic brands like Gazelle, Batavus, BSP, Burgers, Cortina, and more — available in the USA for the first time!