How many questions must the MTA face before they can put in a toll?

MTA Chairman and CEO Janno Lieber said on Wednesday that the federal government’s litany of technical questions in response to a draft environmental assessment on the congestion pricing program has knocked the year-plus schedule slightly off course. Although the agency was supposed to reveal the draft EA to the world in June, Lieber said that was no longer the case.

“We are still struggling with the federal government’s 425 comments on the environmental assessment,” he said. “In some cases, we’re working with the feds to nail down, ‘What exactly do you want us to do?’ And that has had an impact that is right now at least a month on the schedule. Our team is working their tails off to answer all those questions, to do new modeling, to do new analyses, to re-calibrate everything in response to what the federal agency’s comments have gotten to and it is having an effect on the schedule. We are working to minimize it, but June is by the boards.”

In April, Lieber said that the MTA held up its end of the bargain by sending the federal government a draft document on Feb. 10. According to the transit boss, on March 11, the FHWA responded with 430 technical questions on the environmental assessment, question that the MTA had to answer before it could show the document to the public for another round of comment.

The environmental assessment itself has involved a series of public meetings and traffic modeling that takes into account comments and traffic analyses of how adding a congestion pricing toll to south of 60th Street in Manhattan could affect transportation and emissions in 28 counties in the tri-state region, some of them as far away as the Hudson Valley, Connecticut and southern New Jersey.

The delay is just the latest in a series of roadblocks that have been placed in the way of the traffic toll, which the MTA desperately needs to raise $1 billion in revenue that can be bonded to $15 billion for its 2020-2024 capital plan. In 2020, after the state legislature authorized the congestion pricing program in the 2019 budget, it was revealed that the federal government would have a say in the fate of the program because some of the roads that would be tolled under congestion pricing were federal roads that couldn’t be tolled without federal approval. The MTA then waited almost two years for the Federal Highway Administration to rule on whether the agency would have to conduct an environmental assessment or the more onerous environmental impact statement, a wait that advocates chalked up to political interference from the Trump administration.

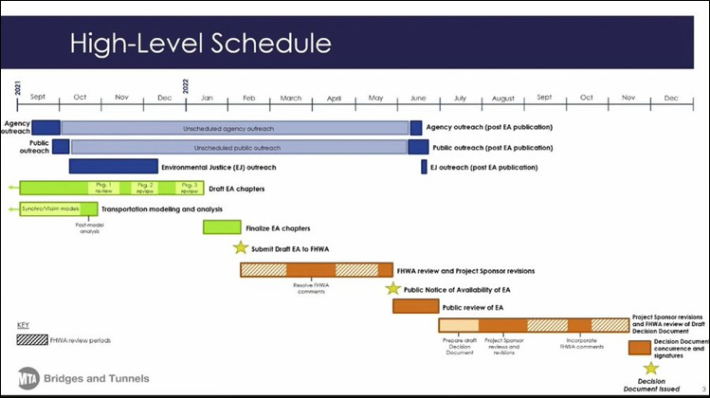

Finally, in March 2021, the newly elected President Biden allowed the process to lurch forward as the FHWA announced the MTA could do an “environmental assessment with enhanced public outreach” to study the environmental effects of the toll that cuts down on the amount of pollution-spewing cars in a given area. The MTA and federal government eventually reached an agreement on a 16-month schedule for the study and outreach involved in the assessment, one that was supposed to last from September 2021 to December 2022, potentially clearing the way for the toll to start in 2023.

Despite the size of the study area, analysts said they were confused by the latest delay wrought by the federal government.

“It is a little confusing, frankly, because the White House has indicated they want a very climate-friendly, equity-oriented transportation agenda,” said Regional Plan Association Executive Vice President Kate Slevin. “But when it comes down to actually advancing something like that, it’s met with similar resistance to more highway oriented projects.

“I hope someone in Washington, DC takes notice that they have their largest metropolitan area desperate for this pro-climate policy to get going. I know the staff at the MTA is working very hard to advance it. And so I hope notice is taken by the White House that this needs to advance at a faster pace,” Slevin added.

Although Lieber cautioned that the delay of the public reveal of the EA didn’t mean that congestion pricing was knocked off of its potential launch date of early to mid-2023, advocates said that the delay did show that the FHWA was not treating the study or the moment with the urgency that was needed.

“Transit riders are sick and tired of federal bureaucrats who fear and loathe New York City delaying smart climate, air and transit policy,” tweeted Riders Alliance Director of Communications and Policy Danny Pearlstein. “The world is burning, the region is gridlocked, and still the subway isn’t reliable or accessible. GTFO.”

Transit riders are sick and tired of federal bureaucrats who fear and loathe New York City delaying smart climate, air and transit policy.

— Danny Pearlstein (@dannypearlstein) May 25, 2022

The world is burning, the region is gridlocked, and still the subway isn't reliable or accessible. GTFO.

cc @SecretaryPete @SenSchumer https://t.co/LpgoTi2Cjm

Other analysts said that the FHWA was too used to working on auto-centric projects and were treating congestion pricing with the same kind of fear and loathing state Departments of Transportation treat non-car infrastructure projects.

“They are really used to transportation projects that have to do with cars and making cars go faster,” said Tri-State Transportation Campaign Director of Regional Infrastructure Projects Felicia Park-Rogers. “They are not used to working on transportation projects that have to do with moving people away from using cars and incentivizing transit, and they’re not used to working at a scale of 28 counties and 22 million people for a single project.”

Rogers did say that there are other pressures coming to bear on this particular congestion pricing project, particularly since the federal government is trying to work through the issues around it under the assumption that other cities in America will want to institute their own traffic toll. But Rogers said it was fair to ask why New York’s attempt to reduce the amount of cars coming into Manhattan and fund needed transit improvements has to be slowed down just because other cities will want a bite at the apple.

“I think that would be a great question for Secretary Pete Buttigieg. He indicated that this is a priority, and I don’t know if he knows what staff is doing, but what they’re doing is significantly slowing us down,” she said.

And even in blue New York, there could be political consequences for gumming up the works for too long.

“If we don’t get this program in place, and we have further deficits in the MTA capital program and fewer tools to manage congestion, people are going to be looking at DC and saying, ‘Why didn’t you let this move faster?’ People will will start to blame people at the White House and people down there if it continues to linger too much,” said Slevin.

A spokesperson for the FHWA did not respond to a request for comment.