Editor’s note: This is the latest in Streetsblog’s ongoing coverage of revanchist movements across the city to remove bike lanes, eliminate open streets or discriminate against delivery workers by a small minority of New Yorkers who own cars. It is not Streetsblog’s mission to give a voice to people who oppose the goals of the livable streets movement, but periodically, we do like to focus on their complaints so that members of the movement can see what the opposition is up to. This story is part of that effort.

Is it the people’s street? Or just the people who eat?

Even the people who are protesting the city’s outdoor dining — yes, Virginia, they do exist — can agree on one thing with those who love the popular program: the city needs more car-free public areas and greenspaces. But that’s about where the harmony ends.

A group of about 40 West Village residents gathered on Cornelia Street on a recent Saturday to air a litany of grievances against the outdoor dining program, which restaurants say helped them stay safe and alive during the pandemic. The opponents offered sometimes contradictory arguments against the program, saying that the curbside dining structures looked like “slums” — but that those slum-like streeteries would also raise rents in the already tony neighborhood.

But overall they said their concerns about late-night noise, trash and sidewalk crowding were steamrolled under a rush of hastily built dining sheds, and want more input and oversight of the revolutionary program that has potentially forever changed the way New Yorkers use the streets. For them, it comes down to one question: who are the streets for in the post-pandemic era? Are they truly for the people, or just for diners willing to pay $30 for cacio e pepe?

In pockets all over the city, small brush fires of resistance have broken out to scorch Mayor de Blasio’s pandemic-era open space initiatives, mostly from car drivers who think any reduction in their space is a hellish “nightmare” (or, as one opponent said on Monday, the 34th Avenue open street will "devastate a whole neighborhood"). Some of the complaints come from people who vacated the city for their country homes during the depths of the pandemic, only to come back and find those of us who lived through the silence, sirens and protests of 2020 now partying in the streets like we blew up the Death Star.

But the Cornelia Street protest is slightly different: this angry crowd is not entirely comprised of parking-hungry car-owners screeching about losing parking like a car alarm that won’t shut up. They say they supported outdoor dining during the heart of the pandemic, but it got out-of-hand quickly. They want more say in the long-term status of the program, and question why public street space is going to just one industry — restaurants and bars — instead of just going directly to the people.

“I think it’s fine if they want to get rid of cars,” Augustine Hope, who’s lived on Hudson Street since 1993, told Streetsblog. “But why do they have to give the space to a restaurant? The space belongs to all of us. … I don’t give a shit about the parking.”

The irony, of course, is that Cornelia Street provided both a backdrop for their complaints, and a convenient, car-free place to meet and discuss them. It’s a tiny but picturesque strip that’s a block off from the much more hectic Sixth Avenue, running between West Fourth Street and the front door of Murray’s Cheese Shop on Bleecker Street.

It’s long been home to restaurants and bars, and, now, a handful spill into the street. It also has a laundromat, a 24-hour store displaying large glass bongs in the window, and a shop that sells CBD from large glass jars. Taylor Swift, the ultimate New Yorker of dubious credentials, said she once rented an apartment on the block.

Micki McGee, who’s lived in the Village for 31 years, said she sees the outdoor dining situation as a multi-billion dollar real estate giveaway to the restaurant industry.

“I’m not a fan of having free public parking in perpetuity for New Yorkers,” said McGee, a sociology professor at Fordham, who noted that she lived in Tokyo, where residents famously have to prove they have a parking spot before they’re allowed to buy a car. “We’ve been giving away public parking for years. Are we just gonna hand it from one industry to another? Or is it really public space?”

Josh Spodek, who at 49 was one of the youngest people in the group, thinks outdoor dining is leading to more single-use plastics in neighborhood trash cans (although he was standing next to Tacombi, where diners ate out of reusable cups and plates), and envisioned a greener thruway.

“This could be gardens, this could be playgrounds with kids, this could be bike parking,” said Spodek, who’s lived on Greenwich Avenue since 1999. “At least if it’s going for private stuff, there could be a democratic process where public land is transferred to private citizens without anyone paying for it.”

The group — Coalition United for Equitable Urban Policy, or CUE UP — argues public space shouldn’t have to be transactional, which is a point some anti-capitalist urbanists have raised, too. But in a city that won’t even risk putting a single bench in a $1.6-billion new train hall lest an unhoused person have a place to tie his shoe for a second, outdoor dining has been the best mechanism for reclaiming street space from cars, for now.

“It could have more trees,” McGee. “It’s a great block. I shouldn’t have to spend $15 for a cocktail to sit outdoors in a public space.”

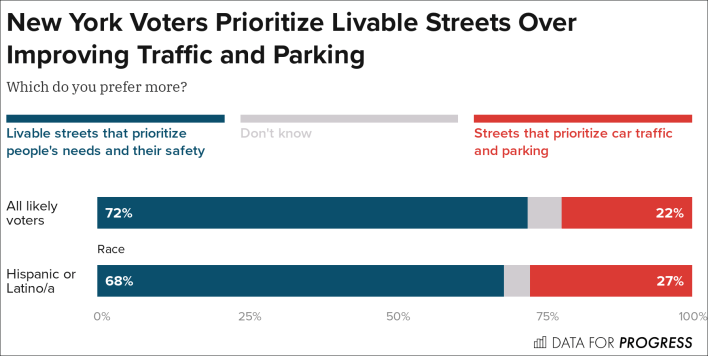

CUE UP is not exactly riding a wave of public support: in a poll commissioned by Streetsblog's parent company Open Plans and compiled by Data for Progress earlier this year, support for outdoor dining was clear: 67 percent of people surveyed said “the city was right to close its streets to cars and open them to pedestrians and restaurants.”

So are opponents just fun police, the kind who long for a Village of the 1990s that is looooong gone, who hate the people who’ve moved in and blast Olivia Rodrigo instead of the cabaret the now-shuttered Cornelia Street Cafe used to offer?

“This restaurant has had a lot of squealy girls today,” said Amy Gillcrest, who’s lived on the street since 1989, pointing to the domed outdoor dining structure of Tacombi.

Their complaints did stray far from outdoor dining at times: noise from Airbnb parties on the street, public intoxication, the beeping sound of backing-up delivery trucks, trash cans overloaded with Starbucks cups and to-go drinks. Some of it is certainly tied to the fact that New Yorkers are enjoying a post-pandemic rumspringa: the weather is nice, the masks are off, tourists are coming back and everyone deserves a stiff drink. Nearby Washington Square Park, which has no outdoor dining, has been the target of identical complaints from neighbors.

“We feel like our neighborhoods are becoming more and more one dimensional,” said Leif Arntzen, who has lived on the street since 1989 and organized Saturday’s meet-up. Arntzen said residents have complained to the community board, but it’s gotten them nowhere. “I really question what is a neighborhood? Is it the people that live there? Or is it just about restaurants and bars?”

Of course, there were a few predictable complaints from car owners who bemoaned the loss of free parking, something that takes public space for the benefit of only a few people. Arntzen, 64, said he can’t get to his work in New Jersey without a car, and fell back on a dubious car-owner argument: having those parking spaces is more green because it means he doesn’t have to circle the block as much looking for parking.

De Blasio has lucked into rare praise by opening the streets to dining. It’s something, supporters say, that puts New York on par with European cities, where you can linger all day and people watch at a sidewalk cafe without fear of being crashed into by a Hummer rocking truck nuts.

CUE UP supporters say eur-wrong if you think that’s an improvement.

“This is nothing like a European city,” said Hope, 59, and originally from England. “I don’t want to be rude about the slums of Brazil or Delhi, but this is like a slum.”

A thread about the issue on the neighborhood Nextdoor page is even more dismissive of the idea, where one Village resident wrote, with privilege dripping from the pixels: “If I wanted to feel like Paris, I'd go there. New York should feel like New York!” (It's worth noting that the protesters hail from a neighborhood with a median income far higher than the wages earned by the restaurant workers whose livelihoods they would curtail.)

And then there is the issue of emergency vehicle access, a thing no one seems to complain about when gridlocked traffic or parked cars are the culprit blocking a fire truck from getting anywhere. Besides, the FDNY has been consulted, said agency spokesman Frank Dwyer, and that department officials “speak regularly” with the Department of Transportation “on all manners of transportation issues/projects and look to address if/when challenges arise.”

But for all these varied complaints, there’s no kill shot likely to make a dent in outdoor dining yet: The mayor announced last fall the outdoor dining program would be permanent, a move the City Council backed. All the major candidates in the race to succeed de Blasio have stated support for the program, too.

"I'm not gonna pray at the altar of parking," the mayor, who still spent most of his eight-year term being driven around in an SUV and did little to discourage a pandemic carmageddon, told reporters earlier this month. A spokesman for the Department of Transportation, which oversees outdoor dining, did not share the group’s concerns.

“Open streets and outdoor dining as a whole have been hugely successful and remain a key part of our city’s recovery,” spokesman Scott Gastel said. “DOT will continue to work with our fellow agencies to make sure open streets setups work for all.”

Respondents to the Streetsblog poll also supported something that could address the one of the protesters’ complaints: 50 percent agreed that trash and other sidewalk clutter should be moved to the curb lane (as in, trade a parking spot for a trash collection spot) instead of the sidewalk (only 31 percent disagreed with this idea).

Mountains of trash are not solely a creation of outdoor dining; there is always trash on New York City sidewalks in the late afternoon.

“The trash hasn’t changed,” one restaurant employee, who didn’t want to be named because he said the protesters have been harassing his customers, told Streetsblog. “It’s New York City, there’s rats.”

It’s notable, he said, that the people complaining about outdoor dining were older, and almost all White; younger residents in the neighboring building have not complained, he said.

Outdoor dining, he said, “has been a lifeline” for the business.

Restaurant workers on the block mostly rolled their eyes at the demonstration. The group, they said, has been harassing the eateries for weeks, slapping anti-outdoor dining stickers on their structures, bothering customers, sending constant emails and misrepresenting the situation on the street.

Bartender Jordan Gentil at Palma laughed at the group, and didn’t see what the fuss was about.

“I’m from Italy, we’re used to eating on the street,” Gentil said. “We’re going to keep this for parking? What’s the difference?”