Mayor de Blasio says his open streets are "permanent" — but he isn't budgeting any money to make them a permanent part of the streetscape.

Monday was budget day for Hizzoner, who trotted out a $98.6-billion plan [a summary is here] that includes $4 million in new funding for the open streets program. But that money is only for "signage, barricades [and] moveable street furniture," plus "financial assistance for many new and existing open streets partners," and not for capital expenditures to convert barricade-protected open streets into true car-free plazas or promenades, as some supporters have demanded.

In a background briefing on Monday, officials with Office of Management and Budget couldn't say how many open streets can be funded with the $4 million — the Department of Transportation is taking applications from existing and new open space volunteer groups through May — but were very clear that there is no money in the nearly $100-billion budget to build something truly permanent.

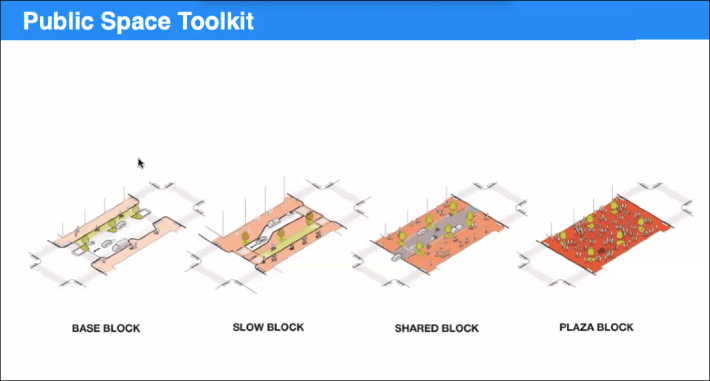

That's counter to what DOT officials have been telling open space advocates — among the Council Member Danny Dromm of Jackson Heights — who have been led to believe that public plazas are, indeed, part of the DOT toolbox for open space. The image below was indeed presented to Queens residents earlier this year:

And in an interview with Streetsblog last week, DOT Commissioner Hank Gutman said that the plaza model "is available if the community support is there."

The budget people could not say how many open streets could be funded with an infusion of $4 million for materials. DOT did not initially respond to a request for comment, but later spokesman Brian Zumhagen sent over the following statement:

Open Streets began as an emergency program; we are now making it permanent and putting serious budgetary resources behind it. While we can’t be prescriptive about how many miles will be in the program while applications are still open, we are confident this funding will enable us to meet demand and increase the quality and quantity of items and activations provided to our community partners, and prioritize the hardest-hit neighborhoods.

Dromm had told Streetsblog last week that he stands ready to provide capital funding if the DOT wants to create a 24-7 linear park in open-space-deprived Jackson Heights, but the agency has not contacted him yet, he said.

In addition to the $4 million for open space materials and support, the mayor also announced $8.5 million for the ongoing open restaurants program, which transforms streets such as Arthur Avenue in The Bronx, Fifth Avenue and Vanderbilt Avenue in Brooklyn into open-air dining piazzas.

As with the open streets budget, it's unclear how far $8.5 million will go, but the money will be spent (per City Hall) to:

- Staff up to manage the program as we work toward making it permanent

- Review suitability of locations and applications

- Inspect outdoor dining setups to ensure compliance

- Revamp the online application system

- Expand the free giveaways of barriers and sandbags to help restaurants create compliant setups.

Many business strips have found themselves having to raise money from their neighbors to sustain the open restaurants program, as Streetsblog has reported, but at least one organizer of a neighborhood effort told Streetsblog that it was surprising that the city was putting far more into open restaurants than open streets.

"Open restaurants conveys a lot of value to restaurants already, some of which could presumably be recaptured by the city to pay for the administrative tasks cited in the announcement," the open restaurant volunteer said. "Unlike open streets, open restaurants has virtually no ongoing labor component that needs funding. And frankly, the benefits of open restaurants in a post-COVID New York City are less clear. I hope that the city moves to fund labor for open streets programs to reduce dependence on volunteers. I believe that is necessary to get to a policy that makes open streets accessible to all neighborhoods regardless of median income."

Perhaps anticipating that line of criticism, City Hall spokesman Mitch Schwartz that the total open streets and open restaurants budget money is "a major step toward codifying this program permanently."

"We’re very excited to support the outstanding community groups who’ve helped make this program such a success," he added.

And Transportation Alternatives went through the roof on Twitter, though Erwin Figueroa, the group's director of organizing, added that open street supporters "still need Mayor de Blasio to implement solutions that will secure the program in the long term."

"We will continue advocating for investments in permanent on-street infrastructure, self-enforcing streets, and a new approach to open streets management that relieves the burden on community volunteer groups and expands the program equitably across the city,” he said.

BREAKING NEWS: @NYCMayor announces $4,000,000 to fund #OpenStreets in his Executive Budget! This money will crucially expand & strengthen the program.

— Transportation Alternatives *Vote on Sammy's Law* (@TransAlt) April 26, 2021

We'll also continue our advocacy for permanent infrastructure, design & management solutions for these spaces in the long term. pic.twitter.com/HOACHcoC8V

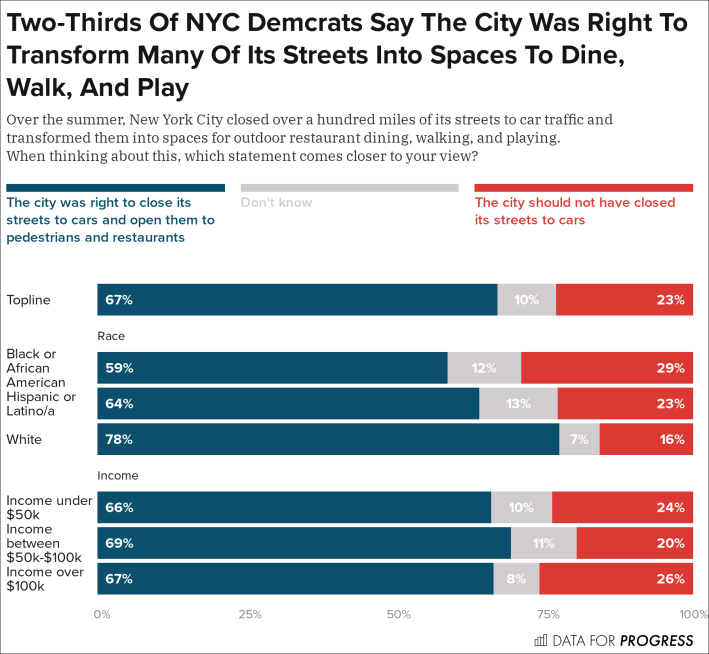

There is widespread support for both the open streets and the open restaurants programs. In a survey of 591 registered voters taken in March, Data for Progress found that 67 percent of New Yorkers think the city "was right to close its streets to cars and open them to pedestrians and restaurants." (See chart below.)

In another question, 72 percent of respondents said they prefer "livable streets that prioritize people's needs and their safety" to 22 percent that said they prefer "streets that prioritize traffic and parking."

To show the scale of the mayor's open streets and open restaurants announcement, the city will allocate far more to other programs in the $98.6-billion "Recovery Budget":

- $100 million in grants to small business.

- $25 million for tourism

- $33 million to resume the collection of organic trash

- $33 million for the Cure Violence and Advance Peace crime-prevention programs.

In addition to day-to-day operations, the mayor did reveal that there is $161 million budgeted for as-yet-unrevealed "Vision Zero capital projects," plus a whopping $723 million to finish the Manhattan greenway (construction won't start until 2023).

The greenway expenses are so high because the remaining gaps are the most difficult to bridge (see chart above). City Hall spokeswoman Laura Feyer broke down the expenses thus:

- Inwood (Harlem River waterfront from Sherman Creek/Academy Street to the University Heights Bridge): $307 million.

- Harlem/Washington Heights (Harlem River waterfront from 145th Street to Highbridge Park): $170 million.

- UN Esplanade (East River waterfront between E. 41st and 53rd streets): $117 million.

- East River “Pinch Point” (currently a narrow walkway between E. 13th and 15th streets): $129 million.

City Hall also revealed that the total budget for bike boulevards promised in the State of the City address is just $300,000 and the budget for the Brooklyn Bridge bike lane is $1.7 million.

And the initial work to create a dedicated pedestrian lane on the Queensboro Bridge so that walkers and cyclists do not have to share a single line for two-way traffic will cost $5 million through July, 2022.