Homeless people seeking shelter in the subway system is neither a transit issue nor a policing issue — but city and state leaders are now battling over different ways to move people along or criminalize them without addressing the central issue, transit and homeless advocates charge.

“Homeless people in transit is a reflection of the housing crisis — it’s not something that can be addressed by the MTA and NYPD,” said Danny Pearlstein of Riders Alliance. “People need a safe, private place to live. If every New Yorker had that we wouldn't have a problem with homeless people on the subway.”

MTA New York City Transit President Sarah Feinberg said last week that she was “losing patience” with the number of unsheltered New Yorkers sleeping in subway stations and cars amid the coronavirus crisis, and called on Mayor de Blasio to do more — echoing the complaints of transit workers and other riders, the majority of whom are essential and still reliant on the system to get to work.

The mayor initially said the situation was under control, but changed tack days later, releasing a plan that called for the MTA to close stations at the end of 10 subway lines for five hours starting at midnight so that workers could scrub them clean, and cops could clear out homeless folks. He said the city would work with the MTA to provide shuttle buses to take passengers to their final stops.

The plan required MTA approval, but Feinberg initially begged de Blasio to send in more cops — a dynamic between the NYPD and transit users that has proven problematic and dangerous for vulnerable New Yorkers.

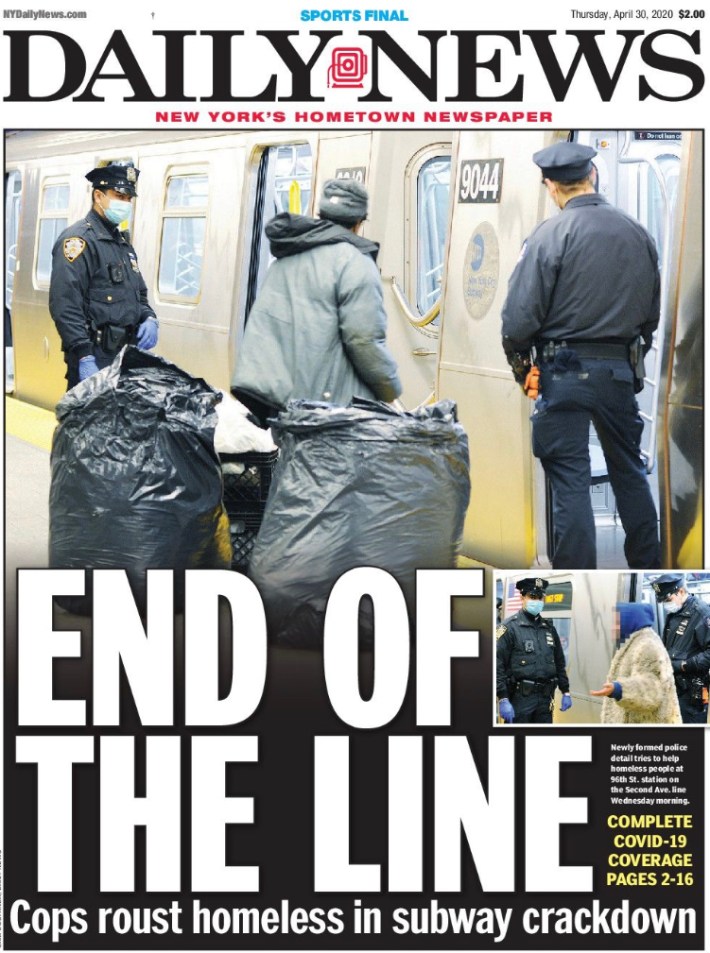

Feinberg said that on Monday night, 40 cops, six MTA police officers, and 10 social service workers descended into the World Trade Center station to remove 100 homeless riders; on Tuesday night, 20 cops, seven MTA police officers, and 10 social service workers did the same thing at the 96th Street station.

Those asked to leave were offered social services, Feinberg said. But at least one homeless man kicked out of the 96th Street station was discovered still wandering the streets hours later, according to the Daily News. The mayor has said in the past that getting a homeless person into the shelter system is not so simple as offering help; it takes many contacts by an outreach worker to gain the trust of a homeless person, he has said.

On Wednesday, Feinberg conceded that the MTA is “open to anything that resolves the issue,” but her latest policy proposal focused on policing most-vulnerable people:

- no person is permitted to remain in a station for more than an hour

- no person can remain on a train or on the platform after an announcement that the train is being taken out of service

- no one may use a wheeled cart greater than 30 inches in length or width, including shopping and grocery carts.

Imagine what it is like to sleeping on the train and woken up by 35 (!) police.

— Picture the Homeless (@pthny) April 29, 2020

Then choosing between an overtaxed hospital (which will more than likely discharge back to the streets/subway) or a crowded shelter DURING COVID-19? #HomelessCantStayHomehttps://t.co/6hrulcuNN4

Gov. Cuomo, who controls the state-run MTA, proposed no solutions of his own besides offering to spend even more taxpayer dollars on armed officers. He referred to homelessness on the subways as “disgusting.”

“That is disgusting what is happening on those subway cars. It's disrespectful to the essential workers who need to ride the subway system,” Cuomo said during his daily coronavirus press conference on Tuesday. “No face masks, you have this whole outbreak, we're concerned about homeless people, so we let them stay on the trains without protection in this epidemic of the COVID virus? No. We have to do better than that, and we will.”

Cuomo on WCBS now says the MTA just needs to tell him what he needs to do about the homeless on trains. "Whatever they need let them tell me and I’ll get it done." He says MTA should tell him if it needs more police, he'll get more.

— Just your friendly neighborhood transit reporter (@s_nessen) April 28, 2020

And neither Cuomo or de Blasio have done enough to address the root of the problem — a lack of long-term, safe housing, said advocates for the people at the center of the latest political battle.

“Once again, this is an unproductive approach by Mayor de Blasio, Governor Cuomo, and the MTA to tackle the homelessness crisis on the subway. Amid the public health pandemic, we should be focusing on creating more housing for those who need it, not increasing NYPD policing," said Joshua Goldfein, a staff attorney in the Homeless Rights Project at The Legal Aid Society.

Policing doesn't solve not having a home:

— Do Jun Lee 이도준 (@dosik) April 28, 2020

- Feinberg & MTA board used unhoused people one of their excuses to spend $$$ on 500 more MTA cops.

- De Blasio's NYPD doing streets sweeps in covid-19 displacing unhoused people from street (against CDC rec).

- Feinberg: hire more cops! https://t.co/ErdVVAiXCo

its disrespectful that @NYGovCuomo withheld supportive housing funds, plateaued homeless spending & failed to invest in extremely affordable housing/anti eviction services for almost his entire term. In spite of literally building his career and wealth on backs of homeless NYers. https://t.co/1DU6PdYklj

— Jenny (@jennyaction) April 28, 2020

The MTA believes that more people now are choosing to sleep in the subway — in addition to the more than 2,000 homeless the agency counted within the system last year — instead of in shelters because of poor conditions inside shelters that make them more vulnerable to contracting the deadly virus. But if de Blasio and Cuomo want them off the subway, they must provide them with some place safer to sleep, said Giselle Routhier, policy director at Coalition for the Homeless.

"During this pandemic, many homeless New Yorkers are rightfully afraid of crowded congregate shelters, where COVID-19 continues to spread," said Routhier. "If you want to help homeless New Yorkers move off the subways and the streets, you need to offer them somewhere safe to go."

On April 11 — nearly a month into New York's stay-at-home orders — the mayor proposed housing just 6,000 of the city's more than 62,000 homeless people who live in city shelters, in addition to the thousands more who live on the street or in subways, in empty hotel rooms. He added on Monday that city would create an additional 200 new "safe haven" beds for those living on the street or in subways.

"These are the kinds of beds and facilities that help us get people immediately off the street who have reached that point where they're ready to finally come in and accept shelter and change their lives and hopefully never, ever go back to the streets," de Blasio said.

But a safe and private room should be available long-term to any unsheltered New Yorker who needs one, said Routhier.

"The city could open up thousands of hotel rooms and offer every single person on the subway access to them, if only Mayor de Blasio had the political will. This misguided policing strategy will continue to push people further into the shadows and make the situation worse for all New Yorkers,” she said.

Homeless people on the subway is not a new issue — but the ratio of unhoused people to other passengers has changed as overall ridership has dipped by 90 percent during the crisis. And just as in the past, those vulnerable New Yorkers are made out to be the scapegoats of worsening subway service, and of long-ignored problems like inequality and lack of housing, said Pearlstein.

"It's reflective of other systemic problems," he said.

Back in 2018, then-MTA New York City Transit President Andy Byford kicked off a crackdown on the homeless living on subways and in stations. Housing advocates, like Routhier, correctly pointed out that this type of enforcement, without relationship-building and services, would not solve the problem.

"More policing won't stop homeless individuals from taking refuge in the subways because it doesn’t address what people actually need: safe, private space so they can take the advice of health officials to maintain social distance," said Routhier.

And last summer, Cuomo similarly demanded his MTA address the growing problem of homeless New Yorkers living in the subway contributing to delays, without offering them any means of shelter.

So rushing now to put unsheltered New Yorkers in too-few hotel rooms or other pop-up beds is only a temporary solution — decades of inadequate homeless policy, under both republican and democratic governors and mayors including de Blasio and Cuomo, failed to solve the human problem of hard-working transit riders and long-suffering homeless people forced into the same space.

But this time, when the virus has passed, hotel rooms will fill back up with tourists. The two often-sparring leaders can no longer turn a blind eye to the crisis, said Pearlstein.

"The transit crisis and housing crisis are different things, ultimately the governor has an enormous role in both to play," said Pearlstein. "The most important thing right now is to communicate that riders empathize with homeless people who are also transit riders and New Yorkers, and don't feel that homeless people are a scourge or criminal element that someone else should take care of — they're collectively responsible, but look to leaders, look to the governor and mayor, to address the problem in its own terms."