We have met the enemy — and it is our mayors!

A survey of more than 100 urban chief executives released last month by Boston University [PDF] showed that mayors may want to make their roads safer and their transportation more equitable, but the vast majority still consider car drivers to be their top transportation priority.

"On many questions, a sizable portion of mayors appear unwilling to implement — or are unaware of — best practices in transportation planning," the annual Menino Survey of Mayors concluded.

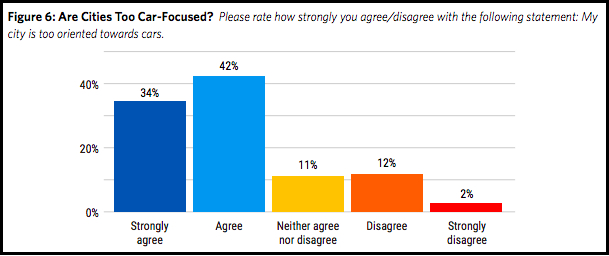

The good news? The vast majority of mayors — 76 percent — agree that their cities "are too oriented towards cars." And a sizeable majority believes that bicycle lanes as a critical part of cycling infrastructure.

But that's about where the good news ends.

“I was really struck ... about [the mayors'] unwillingness to support or implement things that we in transportation planning know are evidence-based ways to make roads safer for vulnerable road users,” Katherine Levine Einstein, a Boston University political science professor, concluded after going through the survey.

About 37 percent of mayors admit pedestrians are unsafe in their cities, and about 48 percent admit the same about cyclists (in fact, the mayors are all deluding themselves; statistics make it clear that pedestrians and cyclists are unsafe in all American cities — just ask Austin or New York City, which experienced a large uptick in fatalities last year, despite six years of Vision Zero!)

The problem is, most mayors in the survey basically admitted they are powerless to solve the existential problem facing their car-choked cities.

"Mayors believe their cities are too dependent on cars and [do] embrace some reallocation of the roadway," the survey found. "However, they do not support other policy changes that can reduce car usage."

The survey of 119 mayors of cities with 75,000 people or more — the majority in the south and west, and mostly white, male Democrats — identified several areas of concern:

Mayors love cars

The simple fact is that municipal executives believe that their job is to make sure drivers can get around.

"When asked to weigh different infrastructure priorities, 66 percent of mayors listed roads as one of their

top three priorities, while bicycle and pedestrian friendliness was a top priority for a mere 22 percent," the survey showed.

Ominously, those results are basically unchanged since 2015, "despite continued increases in pedestrian and cyclist fatalities," the survey added grimly.

Mayors love speed

Here is a fact: When a vehicle strikes a pedestrian at 16 miles per hour, the likelihood that the walker will be seriously injured is just 10 percent. By the time the driver is going 39 miles per hour, that likelihood jumps to 50 percent. And by 46 mph, it's 90 percent. And, lest we forget, slower drivers are able to avoid collisions in the first place.

Overseas, the reduction in speed limits has been the single-biggest factor in reducing road deaths. Oslo and Helsinki achieved zero pedestrian and cyclist deaths in 2019, largely due to slowing down drivers, as Streetsblog USA reported.

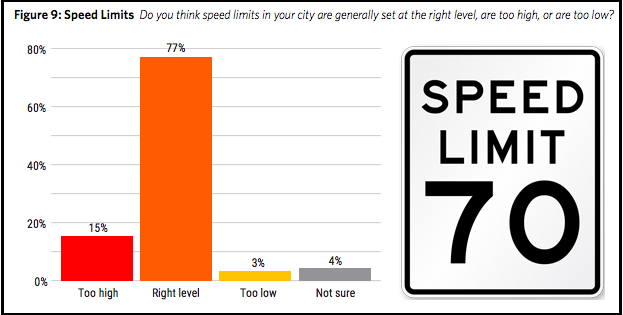

And yet, 80 percent of U.S. mayors believe their speed limits are just right or even too low (see chart) — even though the average speed limit in American cities is far above the 20 miles per hour that has been shown incontrovertibly to reduce carnage.

Even more tellingly, a majority of mayors does not want to increase penalties for moving violations. And over

half of mayors believe that law enforcement in their cities is doing enough to penalize unsafe driving. Only

28 percent disagreed with that.

"Despite the importance of vehicle speed to pedestrian and cyclist safety, mayors largely do not see a need to

change their speed limits, or the way that speeding is enforced in their cities," the survey showed.

Only a small minority — 15 percent — want to reduce the speed limit.

(Caveat: Many cities need state legislative approve to reduce speed limits, so some mayors in the survey may simply have been reacting to the political challenge of making a change. Still there were few mayors in the survey who want to take action.)

Mayors don't see the problem with parking

Activists in more and more cities are seeing curbside parking as the root of all the evils on urban roadways: free parking encourages driving, unavailable curbside space causes double-parking, blocked bike lanes increase the risk to cyclists, cars take up space that could be given to pedestrians or to create mini parks, etc.

Of course, right-thinking mayors know there's a problem at the curbside, the Menino survey writers pointed out:

Ample and cheap parking creates multiple obstacles to implementing evidence-based mobility programs. First, it takes up valuable land area, especially in dense cities. With multiple traffic lanes devoted to parked cars, there is less space available to put in place curb bump-outs, separate bus lanes, and separate bicycle lanes that would improve pedestrian and cyclist safety, and lower transit travel times. Second, when city leaders make it easier to park, they encourage car commuting.

But here's the problem: Mayoral elections are a chicken-and-egg thing. If cities empower car drivers, drivers will use that power to elect mayors who won't challenge the hegemony of the automobile.

Failing to properly price parking "both worsens congestion and creates a constituency of regular drivers who demand more parking, resulting in a potent political obstacle to reforming urban parking systems," the survey says. "Many transportation planners and researchers consequently recommend taking measures that both make parking more expensive and reduce the overall availability of parking."

But mayors are blind: Over 75 percent said their residential street parking — which is often free — is priced correctly. And more than half say the same about metered street parking, which often costs far less than it would be in a truly free market (indeed, one-third of mayors admitted that metered street parking is too cheap in their burg).

But overall, a majority of mayors do not believe there is too much parking in their cities — in fact 27 percent said there is too little parking.

"In concert," the survey concluded, "mayors largely appear unwilling to reduce parking in their cities or make it more expensive."

New York City Mayor de Blasio provides an example of the inner turmoil on this issue. A strong supporter of Vision Zero and an unabashed progressive on equity issues, de Blasio nonetheless rarely challenges the car culture, whether through greater pedestrianization, other car-reduction strategies or, especially, pricing the curb. When the highly dense Upper West Side neighborhood demanded an end to free parking on residential side streets as a way of reducing congestion and increasing safety, for example, the mayor was dismissive.

"If you said we’re going to tell people they can’t park on their street, no, that does not ring true to me," he said late last year. "I’ll look at a whole range of things, but if you said [you'd] go so far as telling people they can’t park on their street, no I’m not there."

Mayors aren't bad people, but they are uninformed

Mayors are willing to sacrifice parking or travel lanes if it means safer cycling. Only 21 percent of the mayors surveyed said they would not risk the pushback from drivers, even if it meant safer roadways for cyclists. The 71 percent that would make roadways safer is somewhat encouraging.

"It may be that mayors oppose general reductions in parking, but are willing to support it when presented with a specific alternative use," the survey said.

But here's the problem: Mayors are woefully ill-informed about the best practices for safer roads.

A disturbingly large majority — 82 percent — believe that painted bike lanes are a safe alternative when

truly protected bike lanes are "too expensive," the survey said (the "too" is highly subjective; in a car-dominated city, voters might conceive of any expense that benefits cyclists as too high).

The central quandary is that painted bike lanes are not, in fact, a safe alternative to anything. And "sharrows" are worse.

"Paint alone — either in separate or shared bicycle lanes — does not improve cyclist safety," the survey said. But very few mayors acknowledge this: 82 percent said painted bike lanes are good enough.

"Mayors are aware of serious pedestrian and cyclist safety issues ... but appear unwilling to implement or are unaware of best practices in transportation planning," the survey concluded.

Republicans are far worse on these things

Democratic mayors tend to be more willing to embrace change that can chip away at the car culture — and the biggest gap relates to bike lanes.

The survey showed that 92 percent of Democratic mayors would create more bicycle lanes even if it means sacrificing traffic lanes or parking spaces, but only 34 percent of GOP mayors would do it.

And the partisan gap is widening, perhaps in concert with the national Republican Party's disdain for climate change solutions and fealty to the fossil fuel and automobile industries.

"These partisan differences have grown by more than 30 percentage points since 2015, when we first asked this tradeoff, with Republicans substantially less likely to endorse this tradeoff or adopt a neutral position than they were four years ago," the survey reported.

And Republicans are more likely to believe their speed limits are correct (90 percent to 72 percent for Democrats). Fact: Those speed limits are not correct.