The city shouldn't spend $4 billion to completely rebuild a crumbling three-tiered section of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, but should instead rehab it into a truck-only highway with a park on top, said City Comptroller Scott Stringer.

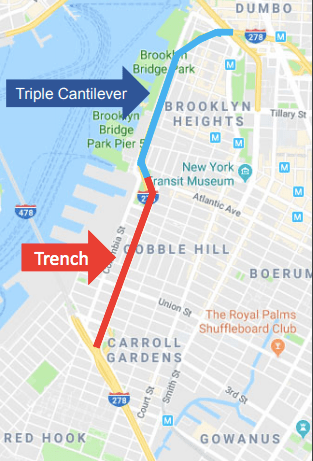

The likely mayoral candidate, who has opposed the city’s plan to fully rebuild a short segment of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway in Brooklyn Heights, is demanding the city study turning the two-mile stretch from in Dumbo to Hamilton Avenue in Carroll Gardens into a truck-only route with a green-space above it to create sustainable pathways for pedestrians and cyclists. The plan also calls for decking over the long-reviled Cobble Hill trench that slices through several neighborhoods.

“We think there is a possible middle-ground that both responds to traffic needs while also dramatically improving local air quality, reducing noise pollution, and rebuilding neighborhoods that have long been divided by the BQE,” said Stringer. “That solution ... is to convert the triple cantilever and the Cobble Hill trench into a truck-only highway with a new, vibrant linear park on top.”

In September, the Department of Transportation proposed two equally expensive — and equally criticized — options for rehabilitating the 1.5-mile stretch of the Robert Moses-era triple cantilever between Atlantic Avenue and Sands Street: a temporary six-lane highway on the historic Brooklyn Heights Promenade until the old highway is completely rebuilt in place, or rebuilding the expressway lane by lane, potentially creating traffic jams for up to 12 miles.

But instead of rebuilding the entire infrastructure, Stringer’s plan calls for rehabilitating just one of the highway’s levels for truck traffic in each direction.

During construction, trucks would run in both directions on the middle-level of the triple cantilever while the Department of Transportation builds the bottom level, so no temporary roadways would be needed, according to his report.

Stringer’s proposal comes on the heels of an even bolder one from his likely competitor in the 2020 mayoral race: Council Speaker Corey Johnson last week demanded the city rethink its much-maligned plan to replace the triple cantilever — which carries 153,000 gas-guzzling vehicles every day — and perhaps just knock it down.

But Stringer conceded that the precedent in other cities to tear down expressways is different from it is here, since those roads were used only by car drivers. The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway carries an average of 14,000 trucks every day, in addition to more than 150,000 cars.

“Nearly all of these highway teardowns have been car-only parkways — which is dinstinctly different from the BQE, which carries some 14,000 trucks per day,” said Stringer. “We can’t redirect those trucks on to local streets, we don’t have enough freight routes in the city, and this section of the BQE serves as an essential manufacturing and warehouse corridor.”

The Brooklyn Heights Association — which is so against the city’s two plans that it tapped its own architect to come up with an entirely new way, which calls for creating a temporary roadway along Brooklyn Bridge Park — applauded Stringer’s proposal.

“We were enthusiastic about the proposal with respect to the fact that it’s a creative idea and that it deserves further development,” said Executive Director Peter Bray.

But Bray also called the proposal a “work in progress” in that more details need to be hammered out, like where the thousands of cars will go when they are kicked off the new truck-only Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. He suggested implementing a High Occupancy Vehicle-only lane, similar to what was proposed for the Williamsburg Bridge before Gov. Cuomo abruptly cancelled the L train closure.

“There are some open questions about how to handle reducing the number of cars that would be displaced from the BQE,” he said. “Under the Comptroller’s proposal, if one level of BQE is proposed to be trucks only, that could be broadened to include cars that had multiple occupants inside as well as buses. It could be a way of the minimizing the possibility of more traffic congestion on local streets.”

Manhattan Institute's Nicole Gelinas echoed Bray’s suggestion in calling for carpool requirements, but specifically during construction of the new highway.

“Something like during construction you have to have four people in the car, that would either get rid of these trip altogether or be more efficiently used,” she said.

Now, Stringer says the cars will likely head to the Hugh Carey tunnel, Belt Parkway, or will rely on public transportation and carpooling.

“Diverting cars to the Hugh Carey tunnel, to the Belt Parkway, to public transit, and to carpooling, we believe that the impacts of closing two miles of the BQE to car traffic can be mitigated to a large degree and will, in fact, incentivize more sustainable transit,” he said.

The Department of Transportation says it is reviewing several options for the BQE, including Stringer’s proposal.

“We are undertaking a thorough review process that will look at range of options for this critical transportation corridor, including the one proposed by the Comptroller, accompanied by substantial community and expert engagement,” said spokeswoman Alana Morales.

Last year, DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg dismissed Streetsblog's call for eliminating the BQE (as the video below shows), but perhaps her views are evolving...