Unlike the East River, the Harlem River is not a wide gulf between boroughs. But covering this short distance still isn't easy for people walking or biking. If you want to get between the Bronx and Manhattan under your own power, the options are intimidating.

Car traffic moves fast near the Harlem River bridges, pedestrian crossings are wide and dangerous, and bike connections are few and far between. Only five of the 11 city-controlled Harlem River crossings (including the Randall's Island Connector) have bike paths.

That is set to change for the better with DOT's release today of the Harlem River Bridges Access Plan [PDF].

"These bridges were built, really, with a legacy of focusing on moving vehicles, and pedestrians and cyclists [were] often an after-thought, if that," DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg said at a press event announcing the report. "We're doing a bunch of things to both humanize these approaches and make them safer."

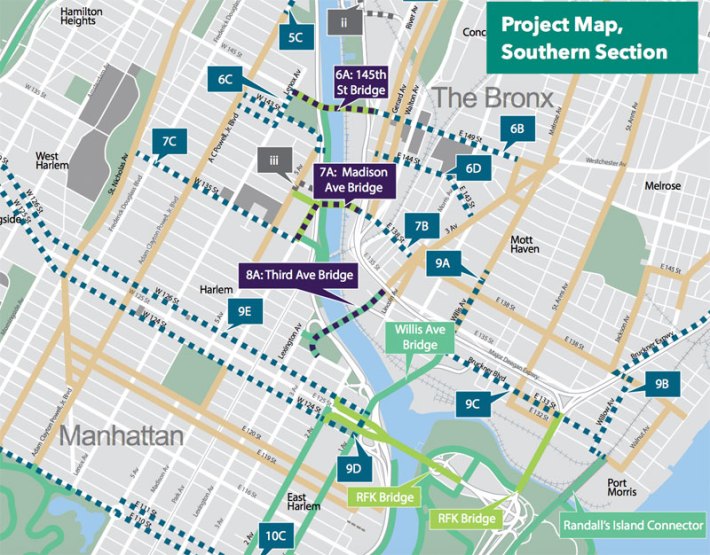

The report spells out expansions of walking and biking rights-of-way on most of the DOT crossings, which will mainly be carried out via capital projects to rehab and replace the aging bridges. Perhaps more significantly, DOT has mapped out bike and pedestrian upgrades on many surface streets connecting to the bridges -- projects that can be carried out faster using low-cost materials.

Trottenberg said DOT began working on the project after the rehabilitation of the High Bridge ignited a discussion about the need for better biking and walking access on the other bridges that cross the river. Advocates campaigned for safer paths across the Harlem River starting in 2014, and the city has been gathering feedback from local residents in a series of workshops going back to 2015.

The timetable for the bridge upgrades will last at least a decade, with DOT folding the work into the capital rehabilitation and replacement of several Harlem River crossings. Next up is the Broadway Bridge, which is in line to be replaced in 2020 and will receive buffered bike lanes under DOT's plan. While adding physical protection to the buffer zone on a bridge should be doable, DOT does not refer to the Broadway Bridge bike lanes as "protected."

One crossing that's not in line for bike improvements is the Third Avenue Bridge, despite connecting to bike lanes on the Bronx side and being a short distance away from protected lanes in Manhattan. The bridge was recently replaced -- without the addition of a bikeway -- and another capital project isn't forthcoming. In the plan, DOT says it will direct cyclists to the nearby Willis Avenue Bridge instead.

Progress should be faster on surface streets, where DOT can work with its quick-build toolkit. For each bridge, DOT has identified a set of street projects to improve pedestrian and bicycle connectivity. Details of these projects have yet to be worked out, but they include several east-west bike connections in Upper Manhattan and the Bronx, as well as upgrades like converting the buffered bike lanes on Edward L. Grant Highway to protected lanes.

In the 1980s and 90s, the city made a concerted effort to improve bike access across the East River, eliminating stairways on the bridges, opening up bridge lanes for 24/7 bike/ped access, and building entirely new structures like the Williamsburg Bridge biking and walking path. That led to more on-street bike projects connecting to the bridges, and since the turn of the millennium, bicycling across the bridges has increased by a multiple of six.

DOT sees the Harlem River projects as similar catalysts for cycling.

"Work we had done on the East River bridges, both on the bridges and on the approaches to the bridges, had an incredible effect on cycling," she said. "[They were] actually some pretty modest improvements, but those improvements really transformed [the bridges] in terms of making them feel safer and more comfortable for cyclists."

Some of the on-street bridge access projects have already been completed, including safety improvements on the Bronx side of the Madison Avenue Bridge, the site of today's announcement.

In addition to protected bike lanes on the bridge approach, pictured at the top of this post, the project expanded pedestrian space and added crosswalks on East 138th Street and the southern end of the Grand Concourse. DOT also converted the semi-circular driveway outside the Finca del Sur urban farm into pedestrian space.

Before the changes, people exiting the 138th Street-Grand Concourse subway station across the street had to walk one block east or west in order access the farm, said Freddy Gonzalez, a Finca del Sur volunteer.

"You had to walk one block up or down just to cross the street. It was very dangerous," Gonzalez said. "We appreciate the stuff that DOT has done for us."