As Zipcar found Robin Chase puts it, a world with autonomous cars can either be heaven or hell.

In the hellish scenario, cities are overrun by privately-owned robot cars circling all day, mostly without passengers, and our transportation system becomes even more isolating. In the heavenly one, fleets of shared vehicles reduce private car ownership, cut traffic, and make streets more conducive for walking and biking.

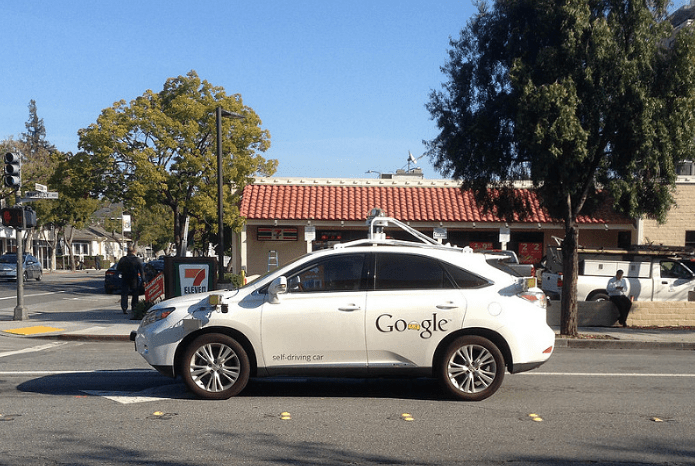

While these technologies are probably many years away from hitting the streets as mature, finished products, public policy decisions are already being made that will determine which path cities follow. Both houses of Congress are crafting regulations that will set the stage for autonomous vehicles, and they're not off to good start.

Legislation introduced by South Dakota Republican John Thune and Michigan Democrat Gary Peters [PDF] would allow carmakers to deploy up to 80,000 autonomous vehicles on public roads to test and refine their technologies. The bill cleared the Senate Commerce Committee in a unanimous voice vote this week.

Watchdogs are especially troubled by the preemption of local governments in the bill, which says states and cities cannot impose "unreasonable restriction on the design, construction, or performance" of automated vehicles. Language like that is too sweeping and vague, and would give cities and states almost no power to regulate the testing of autonomous vehicles, warns Beth Osborne of Transportation for America.

For example, would basic safety precautions like mandating non-lethal vehicle speeds on streets where people walk or bike be construed as "reasonable" by the courts? As written, the bill leaves too much open to interpretation.

"It's not clear if a city could even pass a law saying you have to follow our laws," said T4A's Russ Brooks.

Advocates say the disclosure measures in the bill are too weak. Automakers would only be required to submit annual safety reports to the feds, and the reports would only have to describe changes to the vehicles on the road and "any significant safety deviation from expected performance." Basic data like crash rates per mile would not have to be spelled out, and local officials would not be entitled to any information.

"City and state law enforcement will have zero information about how these vehicles are operating on these roads," said Brooks. "It's really quite terrifying."

In a statement, Osborne said the bill would "creates a climate of secrecy around AV testing or deployment."

Advocates have ample reason to be wary of ceding regulation and oversight to the automotive industry. Recent experience suggests that in the rush to get autonomous vehicles to market, companies are all too willing to cut corners.

California ordered the removal of Uber's self-driving cars after one was caught on video speeding through a red light at a crowded intersection in San Francisco last year. In Pittsburgh, Uber damaged local political relationships by failing to provide data from its experiments with self-driving cars.

T4America says it will work to either amend the problematic sections or strip them out before the bill is brought up for a floor vote.