In NYC's current affordable housing shortage, every square foot counts. With that in mind, the city announced plans earlier this year to relinquish three parking garages it owns on West 108th Street to make way for 280 units of new housing, all of which would be reserved for people earning less than the average income in the area. Naturally, hysteria ensued.

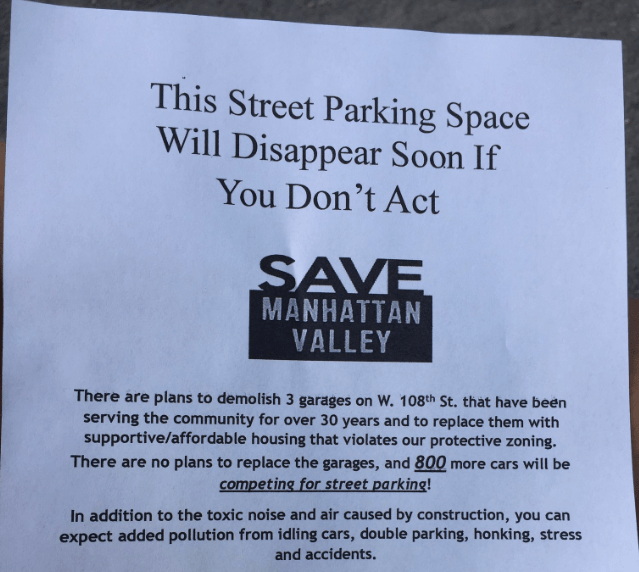

Since the plans were announced, a group of residents organized under the banner "Save Manhattan Valley" to fight the development. "This Street Parking Space Will Disappear Soon If You Don't Act," its fliers read. "In addition to the toxic noise and air caused by construction, you can expect added pollution from idling cars, double parking, honking, stress and accidents."

This is the Upper West Side, served by no fewer than three subway lines (more if you count expresses), several bus routes, Citi Bike, and car-sharing services like Zipcar and Car2Go. All those transit options make owning a car an avoidable expense for Upper West Side households, so nearly 80 percent of them choose not to.

Nevertheless, opponents have predicted doomsday. At a public meeting in March, one neighborhood resident said "fights on the street" would break out because there would be "600 or 700 new cars on the street and nowhere to put them," according to DNAinfo. Sample letters to electeds on the group's website talk of "local residents, Columbia professors, merchants, St. Luke's Hospital workers, and others" being "robbed of their current parking security."

What about housing security? The developer, West Side Federation for Senior and Supportive Housing (WSFSSH), currently operates a transitional homeless shelter on the block. Their proposal would expand that shelter from 90 to 110 beds and build another 140 affordable units and 45 senior housing units on the garage lots. Another 90 units could be built if the city allows WSFSSH to build 11 stories, a tad higher than the current zoning allows.

In response to opponents' concerns, WSFSSH said in June that it would hold off on developing the easternmost lot -- which will ultimately become senior housing -- for five years in order to maintain the 125 parking spots there. But that concession failed to win over opponents, who have since circulated a petition opposing the plan and retained a lawyer, Michael Hiller, to fight it in court.

Opponents have said the ideal outcome would be to build the housing with the same amount of parking that currently exists. A WSFSSH-commissioned study from Nelson/Nygaard found that the lots contain 675 parking spots combined and are around 90 percent occupied during weekdays.

But "having your cake and eating it too" is not possible: The Nelson/Nygaard study estimated that building an underground garage with a capacity of just 118 vehicles would cost $17 million. Simply put, parking is expensive to build, and getting rid of the parking makes it possible to build hundreds of new subsidized housing units.

The good news for neighborhood residents is that there will actually be less traffic on local streets without the garages, not more.

A 2012 report by Rachel Weinberger demonstrated that people with access to off-street parking at home are more likely to commute by car. Subtract off-street parking spaces in the neighborhood, and fewer people will drive to work.

Many people may conclude it no longer makes sense to own a car in one of the most transit-rich places in the nation. For Upper West Siders who truly need a private parking spot, there are 3,500 garage spaces within a 12-block radius, according to the Nelson/Nygaard study. While the study didn't measure the vacancy rate of those garages, even if they're 90 percent full, that still leaves room for more than half the vehicles people currently store on sites to be developed by WSFSSH.

Parking mania has played a role in the defeat of other affordable housing projects this year. Phipps Houses withdrew its proposal to build 209 units of affordable housing over a parking lot in Sunnyside, Queens, for instance. Even though the development would include 200 parking spaces, opponents said that wasn't enough, since it would replace a lot with 230 spaces. Local Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer squelched the project, mainly citing concerns about building height and complaints about Phipps Houses' management practices.

Parking politics will have big implications for the implementation of the de Blasio administration's housing plan. While changes to the zoning code eliminated parking requirements for subsidized housing in much of NYC, getting that housing built will require many neighborhood zonings needing City Council approval.

In practice, that means local council members have the final say. Several council members have acknowledged that parking requirements drive up the cost of housing in New York City, but if they're not willing to stand up to opponents of parking-free or parking-lite housing projects, their enlightenment won't be good for much.