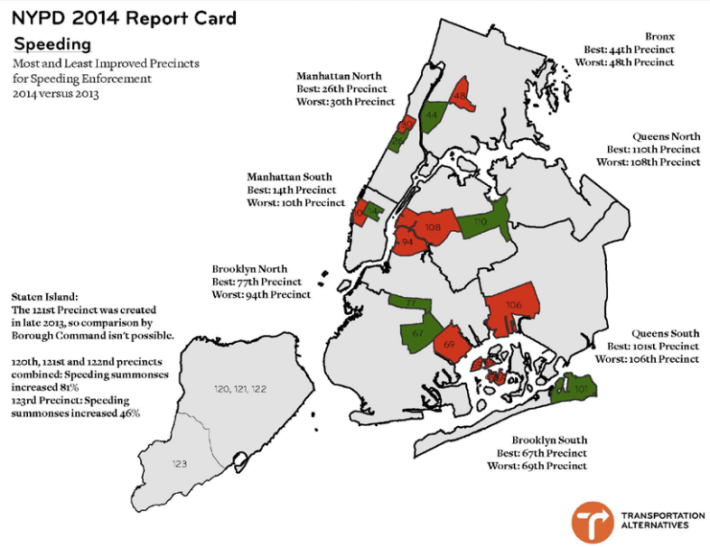

In the year since Mayor Bill de Blasio promised stepped-up traffic enforcement under Vision Zero, NYPD has moved in the right direction, according to a new report from Transportation Alternatives [PDF]. At the same time, enforcement varies dramatically from precinct to precinct, weakening overall deterrence.

TA looked at data from last year and 2013, comparing each precinct's change in speeding and failure-to-yield tickets with the change in injuries to cyclists and pedestrians.

Some precincts rose to the top:

- The 70th Precinct, covering parts of Kensington, Ditmas Park, and Midwood, increased speeding and failure-to-yield enforcement by 243 percent -- that's 310 additional speeding summonses and 832 more failure-to-yield tickets more than 2013. At the same time, there were 33 fewer cyclist and pedestrian injuries within its borders.

- Manhattan South, which covers all precincts below 59th Street, remains a laggard on speeding enforcement. But it did issue 747 more speeding tickets and 2,312 more failure-to-yield tickets last year than in 2013 -- and had 233 fewer bicyclist and pedestrian injuries.

Other precincts had lackluster enforcement and poor safety results:

- The 94th Precinct, covering Greenpoint and Williamsburg's north side, actually issued fewer speeding tickets last year than it did in 2013, while bicycle and pedestrian injuries rose five percent.

- In the Rockaways, the 100th Precinct wrote fewer than one failure-to-yield summons per week last year, as cyclist and pedestrian injuries increased 11 percent over 2013.

The report follows TA's 2013 traffic enforcement report and its check-in on the first six months of 2014.

"The greatest deterrent to the NYPD’s success in reaching Vision Zero is citywide inconsistency," the report says. Precincts right next to each other often have wildly different levels of enforcement, giving drivers the impression that any ticket they receive is just "bad luck" and not a consistent crackdown on dangerous behavior. "Inconsistency undermines any positive deterrent effects of enforcement," TA says. "Every violation that goes unenforced is implicit encouragement for drivers to commit the violation again."

The report recommends focusing enforcement on the most dangerous violations, like speeding and failure-to-yield, and on arterial streets, which comprise just 15 percent of the city's road network but account for more than half of all cyclist and pedestrian fatalities.

Right now, it's impossible for the public to track which streets are the focus of enforcement efforts. Transportation Commissioner Polly Trottenberg says she has spoken with Police Commissioner Bill Bratton about upgrading to geo-tagged enforcement data, which many council members and open government experts want to see as well. In its report, TA also calls for more detailed enforcement information in standard formats that allow for rapid data analysis.

Crash data posted online should also include information on causes of injury, the severity of injuries, and whether the Collision Investigation Squad was called to the scene, TA says.

The report recommends including the stories of traffic violence victims in a comprehensive traffic enforcement component of the Police Academy curriculum. It also suggests using enforcement of the Right-of-Way Law as a metric at NYPD's TrafficStat meetings, where executive officers from each precinct detail their traffic enforcement progress.

"Simply put, traffic enforcement works," the report concludes. "Drivers who receive a summons are less likely to kill or seriously injure someone in the future. This is why the NYPD is critical to achieving Vision Zero."