While safety improvements have saved lives on Queens Boulevard since the late 1990s, when it was routine for more than a dozen people to be killed in a single year, the "Boulevard of Death" remains one of New York City's most dangerous streets. As DOT prepares to launch a comprehensive safety overhaul in the coming months, advocates have published some ideas about how to redesign Queens Boulevard for the Vision Zero era.

Architect John Massengale worked with photo-rendering firm Urban Advantage to produce a new vision of Queens Boulevard, published in the fall issue of Transportation Alternatives' Reclaim magazine. Massengale explains the process:

The images do not reflect the standard DOT approach of focusing primarily on the intersections. Traffic engineers do that because the intersections are where traffic comes into conflict, with itself and with pedestrians and cyclists. Instead, the vision begins with making places where people want to be, and that naturally changes the emphasis to the space between the intersections.

Queens Boulevard cuts a 200-foot wide slice across Queens and remains a deadly street, ranked second in the borough for pedestrian deaths last year by Tri-State Transportation Campaign [PDF]. It used to be worse: Over the years, DOT has responded to advocacy for a safer Queens Boulevard with proposals like wider pedestrian islands at crosswalks, neckdowns, more crossing time, and turn restrictions, which have reduced fatalities significantly. While DOT added some mid-block changes like new on-street parking or pedestrian fences, intersections remained the focus of safety interventions, which didn't necessarily enhance the pedestrian environment.

To transform Queens Boulevard for the Vision Zero era, Massengale focused on turning a 60-foot right of way on each side of the street into "a place where pedestrians are comfortable." This, he says, will set the tone for drivers as they approach intersections. Massengale recommends wider, planted medians with narrower, slower general traffic lanes and protected bike lanes on the service roads.

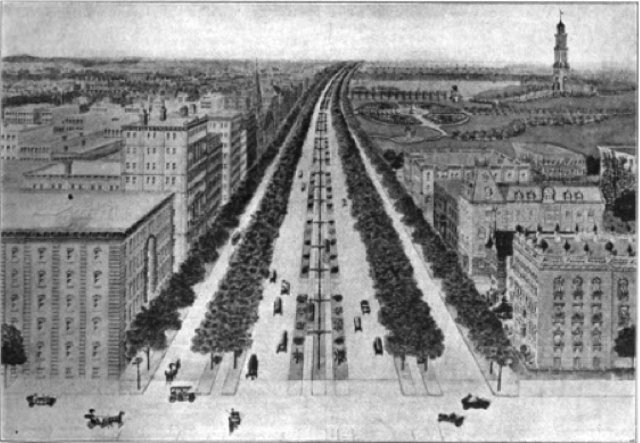

Remaking Queens Boulevard is about more than just street geometry. Massengale also envisions taller buildings along the street to match its width and create a place that feels less like a wide-open highway and more like a grand boulevard. Efforts like this have a long history, including proposals from the Queens Chamber of Commerce for a tree-lined Queens Boulevard as far back as 1914.

Will the de Blasio administration do more than make streets marginally safer with small changes to current designs? Queens Boulevard is shaping up as the test case to see if the city will follow through on its Vision Zero promises. Focusing resources on such a dangerous arterial street would be a promising sign, and Transportation Commissioner Polly Trottenberg says meetings for a redesign will kick off soon.