The MTA has made big strides in recent years to streamline its operations, but without political leadership from Governor Cuomo, the agency won't be able to tackle the high costs and inefficiencies that continue to hamper the city's transit system.

In 2010, after an acute budget crisis, the MTA began a program to cut costs called Making Every Dollar Count [PDF]. Four years later, the MTA is on target to save $3.8 billion since the effort began. By 2017, the agency predicts that annual recurring savings will top $1.5 billion.

MTA leadership felt the cost-cutting program was necessary not only to balance the agency's budget, but also to counter the authority’s reputation for being wasteful and inefficient. Jay Walder, MTA chair at that time, said the program was "the only way we can restore the MTA’s credibility and continue improving service in difficult times."

As the full effects of the Great Recession took hold, the bottom fell out of transit authority’s budget in 2008 and 2009. It was the drop in real estate tax revenue that stung the most, with the MTA’s share of these taxes falling from $1.6 billion in 2007 to $389 million in 2009 [PDF]. By April 2009, the transit authority was facing a two-year budget deficit of $5 billion.

The fix that the state legislature enacted -- a new tax on payrolls -- lacked the bridge tolls recommended by a gubernatorial commission headed by former MTA chair Richard Ravitch. Albany lawmakers repeatedly cited the MTA's reputation for bloat and waste to justify their refusal to enact tolls, much as they had during the congestion pricing debate the previous year.

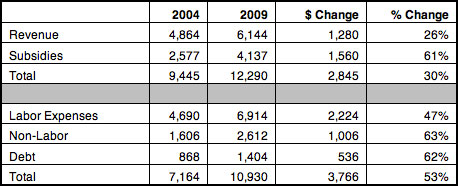

MTA spending did grow rapidly between 2004 and 2009, but much of that was driven by factors outside the agency's direct control. Pension contributions went from $465 million in 2004 to $948 million in 2009; debt service, which could have been kept in check by streamlining the MTA capital program or enacting congestion pricing, grew from $868 million in 2004 to $1.4 billion in 2009.

MTA Revenues and Expenses, 2004 vs. 2009 ($ millions)

Making Every Dollar Count was about reining in operating costs that the agency could tackle directly. Between 2010 and 2014, the MTA figures that it cut costs by $2.7 billion through these initiatives. Some savings were relatively painless -- they did not affect service -- while others, such as the reduction of subway and bus service, inflicted a good deal of pain.

A major chunk of the savings came from changes to the Access-a-Ride program, which had become one of the MTA’s fastest-rising expenses. The MTA saved $423 million on Access-a-Ride costs between 2010 and 2012, according to the state comptroller, which accounts for 23 percent of all the Making Every Dollar Count savings [PDF]. By 2017 the MTA will save $500 million annually on paratransit costs.

About half of these savings were achieved by tightening eligibility requirements. The other half came from renegotiating contracts with private carriers and using taxis instead of vans in some instances.

By requiring more scrupulous examinations of applicants, the MTA slowed the growth of new registrants. The number of paratransit-eligible New Yorkers had risen rapidly, from about 60,000 in 2000 to 170,000 in 2011. Today, the number has dipped slightly to 160,000.

More savings came from consolidating agency functions like IT, reducing administrative headcount, and freezing wages among non-represented staff (the people at HQ haven’t had a raise since 2008). The MTA also renegotiated vendor contracts and improved its procurement and inventory processes.

Other cost-cutting measures were harder for riders to bear. "Programmatic efficiencies" included a reduction in subway car maintenance and cleaning and closing commuter railroad ticket windows. Then there were the service cuts -- two subway lines were cut, dozens of bus lines were eliminated or scaled back, and there were fewer off-peak trains and buses.

The MTA's focus has increasingly shifted to what it called "uncontrollable costs," such as employee and retiree health care, pensions, and debt service, all of which are "driven by factors that are largely outside of the control of the MTA," according to the authority’s budget documents.

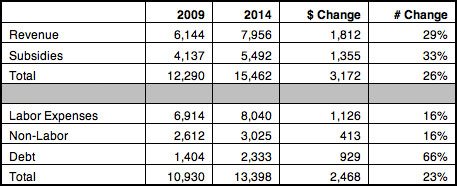

If all goes to plan, savings from Making Every Dollar Count will equal 12 percent of the MTA's operating budget in 2017 (before debt service). Overall MTA costs are still going up faster than inflation. But over the past five years, from 2009 to 2014, the growth of spending has slowed, and revenues are growing more quickly than expenses.

MTA Revenues and Expenses, 2009 vs. 2014 ($ millions)

But another cost, the recent labor agreement with the TWU that was brokered by Governor Cuomo, may knock the MTA's budget back out of balance. The MTA had insisted that any wage increases should be accompanied by work rule changes that enhance productivity. But when the deal was announced, TWU workers got five years of pay raises, including retroactive raises, without conceding any work rule changes.

The MTA has identified only minuscule savings related to its unionized workforce. Possible areas for savings would include one-person train operation, which would mean fewer jobs for TWU workers. The MTA has also tried to shift a certain number of full-time bus drivers to part time, and to eliminate "swing-shift" schedules in which drivers are paid for hours when they are not behind the wheel. Again, the MTA was unable to win these concessions in the new Cuomo-backed deal.

By giving the TWU everything they wanted the governor guaranteed the union’s support in return. When the Working Families Party threatened to pull its support for the governor, the TWU was among the unions that turned around and threatened the WFP. Tit for tat.

The biggest opportunity for savings may lie in the MTA's capital construction costs. MTA mega-projects, which profit an array of construction industry interests, consistently cost several times more than similar projects in other developed countries. And these high construction costs, together with the lack of dedicated revenue for the capital program, have a strangling effect on the agency’s operating budget, causing debt service to skyrocket.

New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer noted in 2011, when he was Manhattan borough president, that the Second Avenue Subway "is costing $2.7 billion per mile of new tunnel." He added, "We cannot build a 21st-century city and compete globally if we continue to spend five, even seven times as much on construction projects as compared to our competitors."

The MTA has made efforts to cut costs in its capital budget, but there seems to be little official dialogue right now about why MTA construction projects cost so much and how the authority can bring costs in line with other global cities. There is a clear opportunity here for the governor and MTA leadership to work together to address these exorbitant costs.

Making Every Dollar Count does represent a change in the way the MTA is doing business, and the savings accrued are significant. More savings could certainly be identified, especially when it comes to capital projects -- and that would require a commitment from Governor Cuomo. But if the past is any indication, the governor is more inclined to let politics trump an effective transit system.