When a street redesign to prioritize walking, biking, or transit is introduced, the headlines are predictable: A handful of business owners scream bloody murder. Anecdotes from grumpy merchants tend to dominate the news coverage, but what's the real economic impact of projects like Select Bus Service, pedestrian plazas, road diets and protected bike lanes? How can it be measured?

A report released by NYC DOT last Friday [PDF] describes a new method to measure the economic effect of street redesigns, using sales tax receipts to compare retail activity before and after a project is implemented. DOT and consultants at Bennett Midland examined seven street redesigns -- including road diets, plazas, protected bike lanes, and Select Bus Service routes -- and compiled data on retail sales in the project areas as well as similar nearby streets where no design changes were implemented.

While the authors do not claim that all of the improvement in sales is directly caused by street redesigns (there are a lot of factors at work), they did conclude that a street's "gain in retail sales can at least in part be attributed to changes stemming from the higher quality street environment." The study also found that the impact becomes apparent relatively quickly: Retailers often see a change in sales within a year of a project being implemented.

While it makes intuitive sense that a better pedestrian environment and high-quality transit and bikeways will draw more foot traffic in a city environment than a car-dominated street, evidence that livable streets are good for business tends to be indirect. Customer intercept surveys have shown that most people in urban areas (including New York) walk, bike, or take transit to go shopping. While customers who drive spend more per trip, they also visit less often than shoppers who don't drive. The net result: Car-free shoppers spend more than their driving counterparts and have a bigger impact on the bottom line of local businesses. Nevertheless, merchants tend to overestimate the percentage of customers arriving by car and insist on the primacy of car parking as means of access.

With this study, DOT used a third-party data source to see how well sales are actually doing in two large categories: retail outlets like grocery stores, clothing stores and florists, and hospitality services like bars, restaurants, and hotels. The study uses state sales tax receipts because they are available on a quarterly basis can be categorized by business type, allowing for an up-to-date and detailed understanding of how retailers are faring on a particular street. Results can be examined before and after a street design change, and compared with sales trends both borough-wide and and on "control streets" nearby that did not receive street design changes.

The project included seven case studies -- three plazas, one Select Bus Service corridor, and three bicycle- and pedestrian-focused redesigns in Brooklyn, Manhattan, and the Bronx. The case studies are: Vanderbilt Avenue from Plaza Street to Dean Street, Saint Nicholas Avenue at Amsterdam Avenue, Bronx Hub, Willoughby Plaza, Columbus Avenue from 77th Street to 96th Street, Fordham Road, and Ninth Avenue between 23rd and 31st Streets.

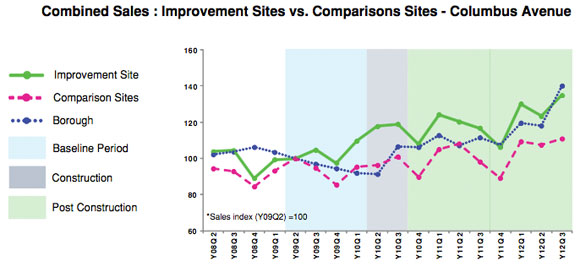

The 20 blocks of Columbus Avenue that received a protected bike lane and pedestrian safety islands saw sales increase 20 percent over two years, while adjacent sections of Columbus that did not get a bike lane saw sales increase by only 9 percent. On the parallel stretch of Amsterdam Avenue, where neighborhood residents want to add a protected bike lane, sales only went up 12 percent.

On Fordham Road near Grand Concourse, merchants complained that the removal of on-street parking for Select Bus Service was killing their business. But the numbers tell a different story: Sales increased 71 percent over three years after the introduction of SBS, outpacing both the Bronx-wide average and three of four nearby comparison sites.

On Vanderbilt Avenue in Prospect Heights, retail sales more than doubled in the three years after a road diet brought bike lanes and pedestrian islands to the street. While some of the increase on Vanderbilt is due to neighborhood change in a gentrifying area, it outperformed not only the borough at large but also nearby comparison sites along Seventh, Flatbush and Washington Avenues.

The intersection of St. Nicholas and Amsterdam Avenues in Manhattan saw a similar, if less dramatic, boost. Sales increased 48 percent over two years, outpacing the borough and nearby comparison sites along Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue.

Sales along Ninth Avenue in Chelsea were lagging when compared to similar nearby retail streets, but after a protected bike lane and pedestrian islands were installed in 2007, sales increased 49 percent over three years, outpacing both its neighbors and the rest of the borough.

DOT said it is looking to use sales metrics in project assessments more regularly, and this data will help it better plan streets with economic development in mind, just as it considers safety, mobility, and health when designing a project.

In the meantime, New Yorkers now have some hard numbers to assuage local retailers who might be skittish about street designs that improve conditions for pedestrians, cyclists, and bus riders.