There’s a lot to like in this morning’s New York Times front-pager summarizing a new study of injuries to pedestrians and cyclists in Manhattan and western Brooklyn. There’s the pull-no-punches headline, “Crosswalks in New York Are Not Haven, Study Finds.” Amen to that. And to the accompanying photo in which a bus, two cabs, and a pedestrian hang out in the bike lane, forcing a cyclist to detour within a whisker of a truck’s protruding mirror.

The study itself, by a team of trauma surgeons, ER physicians and researchers at NYU’s Langone Medical Center, is featured in the April issue of the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. According to the abstract (the full 8-page article is behind a pay wall):

Road safety constitutes an international crisis. In 2010, 11,000 pedestrians and 3,500 bicyclists were injured by motor vehicles in New York City... [Yet] studying fatality or [hospital] admissions data [alone] fail to capture the extent of the epidemic.

The researchers aimed instead “to identify the demographics, behaviors, injuries, and outcomes of vulnerable roadway users struck by motor vehicles in New York City’s congested central business district and surrounding periphery.” They therefore teamed with the Bellevue Hospital regional trauma center, which treated more than 1,400 pedestrians and cyclists injured in the Manhattan Central Business District and western Brooklyn from December 2008 to June 2011.

That database is a potential gold mine. Alas, the Times’ story sheds little new light on patterns of endangerment to pedestrians and cyclists, and may end up perpetuating stereotypes about who causes traffic crashes. The problem doesn't appear to be a windshield perspective; Times reporter Matt Flegenheimer has evinced refreshingly little of the Times’ habitual pro-driver bias since taking over the transportation beat last year. Rather, it’s the age-old pitfall in reporting epidemiological results: the case of the missing denominator.

For example, Flegenheimer reports that “In a finding unlikely to surprise the city’s cyclists, about 40 percent of injured riders were hit by taxis, compared with 25 percent of the pedestrians.” But given that medallion taxis account for a little more than 40 percent of vehicles in motion in the Manhattan CBD (the area in which the bulk of the analyzed crashes took place), one might conclude that, relative to other vehicles, taxis are neutral vis-à-vis cyclists and even a plus for pedestrians.

In the same vein, the Times reports that among traffic victims ages 7 to 17, more than 10 percent of pedestrians and nearly 30 percent of cyclists were using a cellphone or music player. Yet the percentages of all children and teens who use electronic devices while walking and cyclist are also high. Without knowing those “background” levels, one can’t say whether cellphone use among that population is correlated with a greater injury risk, or a lesser one.

Ditto for the “finding” that 15 percent of adult pedestrian victims and 11 percent of adult cyclist victims “were found to have consumed alcohol before the collision.” Even leaving aside that many people consume alcohol without reaching the legally-defined 0.8 percent threshold for intoxication, the victim percentages are meaningless unless they are shown to be statistically higher than for the populations of pedestrians and cyclists as a whole.

At least reckless driving gets its due in the story, though after the jump, and only by implication:

One harrowing take-away from the report is that no area, it seems, can be entirely safe. Six percent of pedestrians were injured while on a sidewalk. Of those injured on the street, 44 percent used a crosswalk, with the signal, compared with 23 percent who crossed midblock and 9 percent who crossed against the signal.

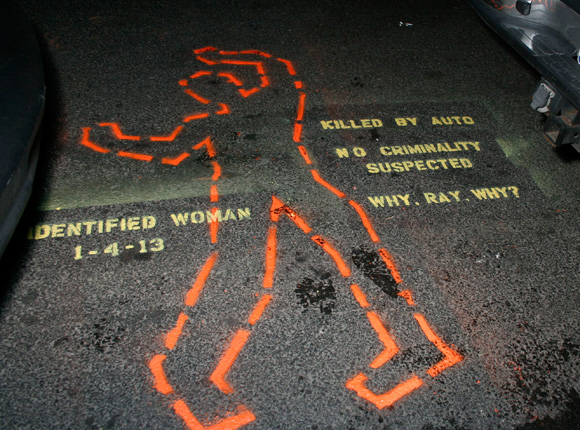

The focus on sidewalk injuries is overdue and thus welcome. The first-ever epidemiological report on NYC pedestrian fatalities, Killed By Automobile (for which I was lead author), found that five percent of pedestrian and cyclist fatalities in the five boroughs in 1994-1997 occurred on sidewalks or other places (such as parks) where driving is prohibited. That the frequency rate (for injuries) has risen to six percent validates the escalated sense of vulnerability in the city following the sidewalk killings of Martha Atwater in Cobble Hill in February and Tenzin Drudak in Long Island City in March, not to mention the sidewalk-jumping episode in East Flatbush last weekend that left a 3-year-old gravely injured and his mother in a coma. Indeed, of the eight street memorials that activists spray-painted around the city a few weeks ago, four are on sidewalks.

Both the NYU-Bellevue study and the Times story underscore the value of data in understanding and curing the aptly-termed road-danger "epidemic.” The irony is that the data that arguably could have the greatest impact on traffic danger — the NYPD Collision Investigation Squad’s supposedly meticulous crash analysis and reconstruction reports — continue to be sealed off from researchers and advocates. Our proudly data-driven mayor goes ballistic on legislators who block traffic-calming speed cameras and lavishes millions on global road-safety studies, yet he remains curiously passive about the opaque state of street safety data in his own backyard.