In the fourth chapter of what's become an enthralling series, UCLA professor Donald Shoup breaks down the incentives at work in the Cato Institute's decision to provide free parking for employees at its Washington, D.C. headquarters. While Cato senior fellow Randal O'Toole claims the choice has nothing to do with market distortions caused by government policy, a look at the tax code suggests otherwise. Joining us mid-series? Read installments one, two, and three.

Randal,

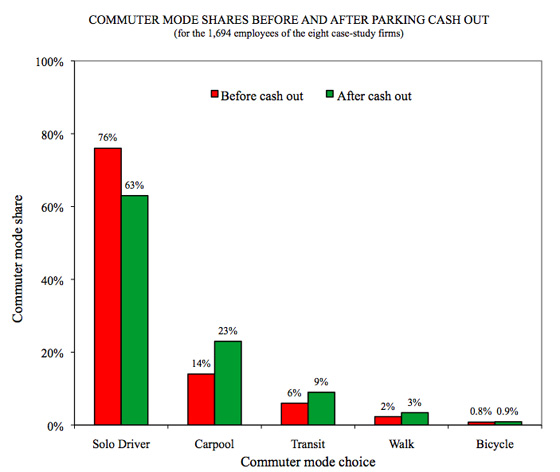

Thanks for your message of October 10. The focus of our disagreement seems to have shifted to employer-paid parking. I have criticized employer-paid parking because it increases solo driving to work and thus increases traffic congestion, energy consumption, and air pollution. In contrast, you say, “I don't see why we, as policy analysts, should be concerned that Cato, or any employer, offers free parking to its employees.”

In defense of this position, you say that Cato voluntarily offers free parking although, as a tax-exempt institution, it is “relatively immune to tax incentives,” and that its decision to offer free parking is its own choice, without any government interference or subsidy. It seems you are saying that whatever Cato does about parking is right if Cato voluntarily chooses to do it. My first response to that line of reasoning is to wonder whether most libertarians place a higher value on liberty than on well-functioning markets. If an institution voluntarily introduces a price distortion, like free parking, should policy analysts not be concerned?

As interesting as that question is, however, it is not germane to our discussion, because you are wrong about Cato’s tax incentives. You should check with Cato’s HR department about taxes, because Cato has the same tax incentives to offer free parking as does any taxable employer.

What are the tax incentives to offer free parking? The Internal Revenue Code encourages all employers to convert taxable wages into nontaxable parking subsidies. With the average 19 percent federal marginal income tax rate and the average 6.5 percent state marginal income tax rate, a commuter faces a 25.5 percent combined marginal income tax rate. Social Security and Medicare add an additional payroll tax rate of 7.65 percent, so a typical commuter’s marginal tax rate on earned income is about 33 percent. The employer (even tax-exempt Cato!) also pays 7.65 percent in payroll taxes. Therefore, the total marginal tax rate on earned income is about 40 percent. Converting $100/month of taxable salary into a tax-exempt parking subsidy of $100/month thus saves the commuter $33 and saves the employer $7.65.

This tax subsidy is a strong incentive for Cato and every other employer to offer free parking at work and thus to subsidize driving to work. It also helps to explain why 95 percent of all automobile commuters in the United States park free at work.

Unwise tax policy distorts the employers’ choices about transportation fringe benefits, and in turn the employers’ misguided fringe benefits distort commuters’ transportation decisions. Chapter 3 in Parking Cash Out explains the tax angles of employer-paid parking.

Employer-paid parking is the most common tax-exempt fringe benefit in the U.S., but it is also an anomaly. Most tax exemptions are intended to promote a public purpose, but the tax exemption for employer-paid parking encourages solo driving to work. As your Cato colleague Julian Sanchez wrote, “heavy automobile use has serious social and environmental externalities, and a socially conscious firm ought not to be subsidizing all that carbon-burning.”

After considering the 40 percent tax subsidy for employer-paid parking, you might rethink your statement that policy analysts should not be concerned if employers offer free parking to their employees. And after studying the tax incentives for employer-paid parking, you may decide to support Congressman Earl Blumenauer’s bill (H.R. 3271) that would encourage many employers to offer parking cash out. H.R. 3271 will not remove the tax exemption for employer-paid parking, but, by requiring employers to offer commuters the option to cash out the parking subsidies as a condition for the tax exemption, the bill will reduce discrimination against non-drivers. So I would very much like to hear your views about how H.R. 3271 will affect the price distortions created by parking subsidies.

Fortunately, we will have the opportunity to debate these issues more formally next Spring, because Jason Kuznicki has commissioned me to write about parking policies in "Cato Unbound." At that time I do hope to take up the questions I posed earlier, and to learn more about how libertarians view individual freedom in a market where unwise government tax incentives have distorted prices.

Another topic I hope to cover in the article for Cato Unbound could be called parking exceptionalism. It seems to me that most people's critical and analytic faculties shift to a lower level of intellectual prowess when they think about parking. For example, some people support fair market prices—except for parking. They oppose subsidies—except for parking. They oppose strict planning regulations—except for minimum parking requirements. Unfortunately, when the conversation turns to parking, rational people quickly become emotional, and staunch conservatives become ardent communists.

As you wrote in your earlier message, “Shoup’s work is biased by his residency in Los Angeles, the nation’s densest urban area.” Employer-paid parking seriously distorts transportation prices in a dense city that has high parking prices, so perhaps I am biased by living in Los Angeles. Similarly, you may be biased by living in Camp Sherman, a hamlet in rural Oregon. You probably never pay anything for parking in Camp Sherman, and therefore you have little daily experience with how a commercial parking market works, or how employer-paid parking affects commuting decisions.

Finally, I have a request. I assume that Cato must have some written policy about how it distributes parking passes among employees. I would appreciate the favor if you would ask the Cato Institute to send me a copy. Thanks.

Donald Shoup

Department of Urban Planning

University of California, Los Angeles