The Adams administration took a victory lap on Wednesday to celebrate record-low traffic fatalities through the first six months of the year — putting officials in the awkward position of feting protected bike lanes at the same time they're arguing in court that there is no difference between them unprotected lanes.

Transportation Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez stood in front of the city’s new Tenth Avenue "extra-wide" protected bike lane on Wednesday and told reporters the total traffic fatalities for the first half of 2025 have dropped to the historic low of 87, tying the first six months of 2018.

Rodriguez proclaimed that “design is the answer,” pointing to the new bike lane, and said is agency is guided by “the value and commitment to reimagine our streets.”

“Our streets are not private, our streets are public and belong to everyone,” Rodriguez said. “At the age of 60 I do this work not to be popular. We have to have the courage to do what is right, even when some of the loudest voices are opposed to change. We have to have courage because we know that lives depend on it.”

But Rodriguez's words rang hollow the day after his agency argued in court in favor of ripping up three blocks of the Bedford Avenue protected bike lane in response to the very types "loudest voices" Rodriguez chided in his comments.

The same department Rodriguez said has “courage” to do what is right has shown a tendency under Mayor Adams to abandon those principles because of complaints from the loudest groups — most recently when Adams buckled to pressure from the Hasidic community of Williamsburg and ordered the three blocks of the Bedford Ave. bike lane removed.

Supporters of the bike lane sued in response, forcing DOT to throw the principles espoused by Rodriguez on Wednesday under the bus in court.

DOT attorney Kevin Rizzo argued in front of a judge on Tuesday that there was no legal difference in "the definition of a bike lane" whether it was protected or unprotected.

Asked about this contradiction, Rodriguez borrowed a line from his boss.

“Mayor Adams says that we are 8.6 million people but we have 35 million different opinions. You know, Mayor Adams has been committed to listen to the community," he said. "We follow the process and the judge will make a decision. Each community is unique, each community is different."

By the numbers

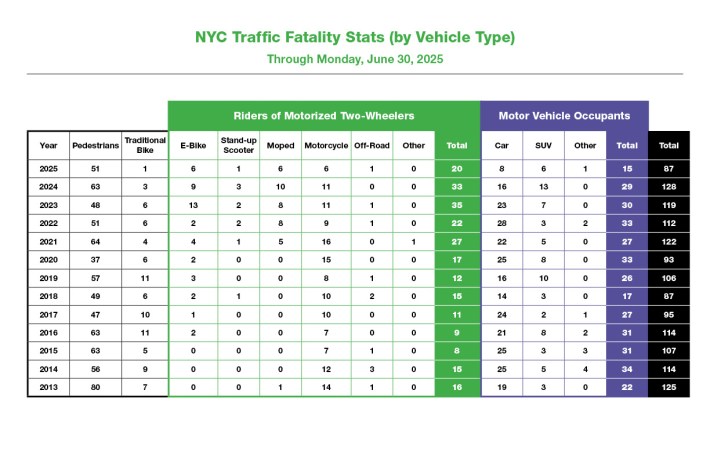

Through June 30, the overall number of traffic fatalities in the city drooped from 128 last year to 87, according to city data — a massive 32 percent decline.

Just one cyclist on a traditional bike died in a crash so far this year, down from three last year. And e-bike rider fatalities have declined from nine to six and pedestrian fatalities have declined from 63 to 51.

The city is still a far cry from its goal of reducing traffic fatalities to zero. After Vision Zero began in 2014 under then-Mayor Bill de Blasio, fatalities declined steadily as the city worked to install speed cameras, protected bike lanes, redesign intersections, and educate New Yorkers. By 2018, there were 87 fatalities in the first six months of the year, a drop from 125 in 2013, the year before Vision Zero began.

The pandemic saw an increase in car ownership, reckless driving and traffic fatalities, which rose to 122 in 2021 and 128 in 2024. The numbers so far this year put the city on place for a lower total, but much could change in the second half of the year.

Experts warned the data isn’t as clear a victory as the administration wants it to be.

"We’ve seen the commissioner do this before where he touts mid-year results. It’s not a good idea because a few bad months will wreck the year," said Jon Orcutt, a former DOT official and director of advocacy at Bike New York.

“It’s a very small set of numbers, so the randomness factor is very high in all of this," Orcutt explained. "In any particular crash there’s a lot of randomness between whether someone is badly hurt or killed."

DOT also tracks “KSI,” which stands for killed or seriously injured.

Serious injuries are also down this year so far, according to DOT, but not by as dramatic of a percentage: In 2024, there were 1,194 severe injuries from January 1st to June 15th; this year there were 1,102 — a decrease of 7.7 percent. Severe injuries are down for every mode except e-bikes.

Why are fatalities down?

In his address to reporters on Wednesday, Rodriguez cited the city’s focus on the three E’s — education, enforcement and engineering — as reasons for the success. One thing that didn’t come up was congestion pricing.

Rodriguez mentioned the city’s expanded speed camera system, the 700 vehicles in the city fleet with speed limiters, protected bike lanes, the NYPD’s ghost car initiative, an increase in enforcement on Vision Zero Priority Corridors, and even Citi Bike reducing its electric bike speeds to 18 mph last year as reasons for the decline in fatalities.

Asked if congestion pricing had a role, however, Rodriguez told Streetsblog it was “too early to tell." He suggested it may not have played much of a role because the outer boroughs saw the biggest drops in carnage.

“It may contribute, however we still have to continue looking at the data,” Rodriguez said. “I do believe that it is important, but I believe that it is too early to say that this reduction happened because of congestion pricing.”

But since the tolling program that charges drivers $9 to enter Lower Manhattan at peak hours was enacted, there have been fewer car crashes in the congestion relief zone, according to city data.

From Jan. 1 through May 6, there were 218 fewer collisions — a 13-percent reduction — in the congestion relief zone compared to the same period last year, Streetsblog reported in May.

Congestion pricing has also changed traffic patterns throughout the city, not just in the zone. The MTA estimates that in April around 76,000 fewer cars per day entered the zone than would have without the toll.

And ridership is up across the city’s public transportation system, meaning more people are choosing transit over driving citywide.

Orcutt said that congestion pricing could be part of the reason why the reduction in fatalities is so significant, but added that to really make lasting change in the numbers, the city needs to do more to get cars out of the way of everyone else.

“To say that street design is driving fatalities down by 30 percent in six months is just not credible because we’ve been doing this stuff for 20 years, so something else is going on, either its luck and randomness, or maybe it is getting those [ghost] cars off the road, or congestion pricing,” said Orcutt.

“If we really want to get fatalities down, we need to be hitting the Streets Plan targets and be more aggressive with the designs and start replacing all the plastic crap that the DOT’s showered the streets with.”