The city has won a $15-million federal grant to install another 600 electric car charging posts along the curbside lane — part of a massive investment in new auto infrastructure that pedestrian advocates say will lock in the roadside for car re-fueling for generations.

The money will bring the city much closer to meeting its stated goal of "creating a network of 1,000 curbside charge points across the five boroughs by 2025,” up from the current 100 electric-car filling stations on city sidewalks. Half of the new charging stations will be in "disadvantaged and low-income neighborhoods," a nod to the areas where many taxi drivers live — and the fact that Uber and Lyft drivers must transition to 100-percent electric (or wheelchair-accessible) vehicles by 2030.

“Supporting the transition to electric vehicles means ensuring that everyone has quick and easy access to chargers — especially taxi and for-hire-vehicle drivers, who will lead the way towards a modal shift,” said Deputy Mayor for Operations Meera Joshi.

But behind the static charge of new EV fueling stations is some old-fashioned greenwashing, pedestrian advocates say. Just as roadways were reconfigured for cars almost a century ago, some see the roadways — which proved their value as public space during the pandemic — again being locked into car domination for another century.

"We would applaud the installation of fast chargers on private properties, as it is done in Europe, [but] installing chargers on the sidewalk constitutes a substantial increase in service that the city delivers to drivers — on the top of free parking on the street, all of it funded by residents who do not drive," said Christine Berthet, the co-founder of CHEKPEDS, the venerable Clinton and Hells Kitchen pedestrian advocacy group. "One used to go to the gas station, now there is at-home deliveries of fuel.

"With 151 traffic fatalities to date in 2024, we are disappointed that DOT [to] make driving more convenient are getting more funding, while safety programs are not," she added.

Berthet was already raising the alarm about curbside refueling stations before Wednesday's grant announcement that came in the form of a City Hall press release (there was no public event). Earlier in the week, Berthet noticed that the city had also applied for an additional $90 million in federal grant money to "incentivize the use of electric-powered vehicles" [PDF, search for project code X77425].

"We strongly object to this project and these policy choices," Berthet said. "We recommend that the portion of the project dealing with sidewalk chargers be removed [from the grant application] and the related funds redirected to safety projects like X77439 intelligent speed assist which will benefit millions and reduce the city’s legal exposure." (The city is seeking nearly $55 million from the feds to equip the city fleet with devices that will prevent drivers from speeding.)

Open Plans joined CHEKPEDS in criticizing the city's priorities, citing Streetsblog reporting that revealed that electric cars tend to be bought by the wealthiest New Yorkers.

"This is beyond frustrating and it’s shocking that the administration would invest so much money in permanent car-centric infrastructure that will serve so few New Yorkers," said Sara Lind, the co-executive director of the group (which shares a parent organization with Streetsblog). "The average resident of a low-income neighborhood is not driving around an expensive EV. What those neighborhoods actually need is decent bus service, but that seems impossible to achieve. So instead we’re just catering to wealthy drivers and permanently subsidizing our public space for their use. If we install these chargers at the curb, it will be harder than ever to repurpose that space for the public. It’s a slap in the face to everyday New Yorkers and a shortsighted move that goes against the administration’s own goals to rightsize our use of curb and streets for cars."

Much of the question about curbside refueling of electric vehicles gets into the notion that such cars are environmentally sound because they issue no tailpipe emissions. But electricity must be generated somewhere, and the new grant will fund only 32 solar-powered charging ports, which will be located inside eight parks," the press release stated. (The DOT said cars would do their refueling only in existing parking lots inside parks, where vehicles already have access and visitors tend to be community residents who park long enough for a full charge.)

Meanwhile, New York State's electric grid generates 46 percent of its power by burning natural gas, a fossil fuel — a practice that cannot be called environmentally sound, the Times recently reported.

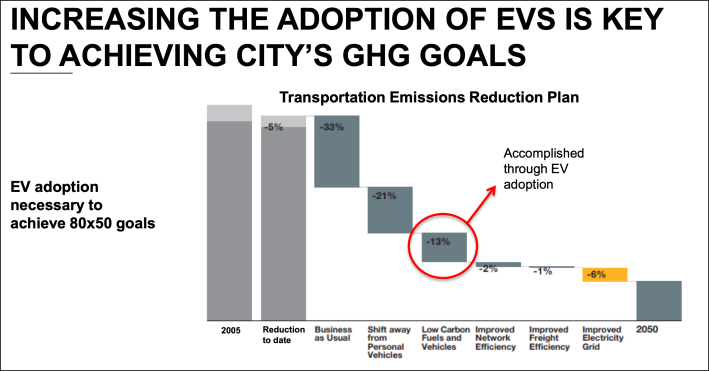

Even as it is encouraging the use of electric cars, the city Department of Transportation has lofty environmental goals. On the eve of the Adams administration, the agency said it was committed to reducing emissions from transportation by 80 percent by 2050, a promise that apparently still holds (DOT declined to comment). As the graphic below shows, the largest share in emissions reduction will be "business as usual," namely the agency's effort to build bike and bus lanes (both of which are well behind targets).

The agency predicts that its efforts to stimulate EV adoption will reduce emissions by 13 percent. But another 21-percent reduction in transportation emissions through a “shift away from personal vehicles.” (The agency declined to comment on how that will be accomplished outside of "business as usual.")

At the same time, the city says it hopes to boost cycling from roughly 2 percent of trips to 10 percent of trips so that sustainable modes of transportation — i.e. transit, walking, biking — rise from roughly 67 percent of trips in 2016 to 80 percent by 2050.

The Adams administration said in 2023 that it would "cut transportation emissions in half by 2030,” but a one-year progress report issued in 2024 only mentioned initiatives in the areas of "buildings" and "food." (The DOT declined to comment.)

Officially, agency spokesman Vin Barone did say that DOT's goal is to increase the share of people who walk, bike and use transit — converting those who "need" to drive to electric vehicles.