New York City plans to upgrade half a dozen docks for maritime deliveries as part of a tiny effort to shift freight off the street that critics said will barely scratch the surface of the pollution, traffic crashes and congestion caused by the 120,000 trucks that pas through the city each day.

Renovations on the six piers in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx will start in late 2025, officials recently revealed to a Manhattan community board [PDF] — but the initiative, backed by more than $5 million in federal funding, won't make a dent in the problems it's meant to address.

“These are positive first steps, but they are not going to do what we need to do to truly move our freight from our roads and bridges onto our underutilized waterways,” said Alex Matthiessen, an environmentalist and director of the newly-launched Blue Highways campaign at Move NY, a coalition that previously pushed a blueprint for the incoming congestion pricing program.

Trucks move nearly 90 percent of all freight in New York City — well above the national average of 70 percent, according to the city's Economic Development Corporation.

The project would divert 350,000 truck miles annually onto the water and other "clean" last-mile delivery vehicles, according to EDC officials — a tiny fraction of the what the the Trucking Association of New York says are seven billion annual truck miles on the Big Apple’s roads.

“If this is the pace that they’re charting, we’re never going to get there. It’s too little, too slowly,” Matthiessen said.

EDC manages the effort, dubbed “blue highways." The quasi-public city corporation plans to install flat top barges to stage cargo at the six East River landings, where small vans and eventually e-cargo bikes could transport the goods for the "last mile," thereby reducing the number of polluting big rigs on the city’s streets.

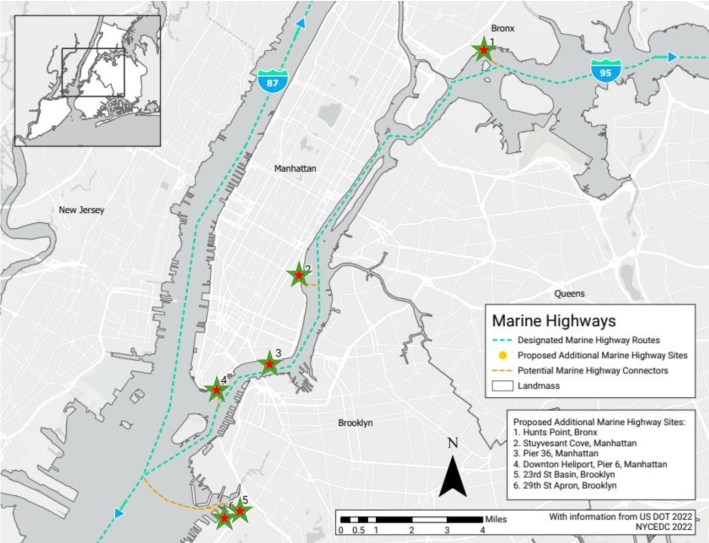

Locations include Oak Point in the Bronx; Stuyvesant Cove, Pier 36 and the Downtown Manhattan Heliport at South Street; and 23rd Street Basin and the 29th Street Apron in Brooklyn.

“These six sites are well positioned to really be unloading a lot of the burden that is being caused by trucks,” Tara Das, a senior project manager at EDC told Manhattan Community Board 1's Transportation and Street Permits Committee on April 3.

Upfront investment

But shifting the city's freight load to water requires more upfront investment in new infrastructure, more collaboration between the city and state and New Jersey, and extensive environmental approvals to build into the water, according to Matthiessen and other experts. Deliveries through the six new piers will be more expensive than loading up trucks and sending them down highways.

“It’s really a slow-moving battleship,” said Tiffany-Ann Taylor, vice president for transportation at Regional Plan Association. “Building anything and building anything in the water in and around New York City is very expensive, right, and takes a long time because of a whole bunch of different environmental rules we have to pay attention to.”

Taylor, who worked at EDC and the Department of Transportation under the de Blasio administration, praised Mayor Adams for giving more attention to waterborne freight — but urged officials to go further.

“The city could be moving faster and also we’re not really clear what the scale of impact will be,” she said. “What does that mean for the scale of goods that will actually be transported? Is it 40 tons a day or is it 4,000 tons a day?”

The city needs to build large, standalone maritimes facilities, Taylor said — rather than just tacking barges to existing piers.

“I would much rather see a whole pier, perhaps along the West Side, completely dedicated to that type of transportation,” Taylor said, rather than “trying to squeeze it in at a heliport where maybe the scale of impact isn’t that great.”

The interest is there

There is a lot of interest in the marine and freight industry, as indicated by EDC apparently getting a “healthy response” to a request for proposals for design and engineering consultants, according to Taylor.

“It says to me that the market is interested and ready to respond if the city allows for those types of investments to be made,” she said.

Shipping companies have run small-scale maritime freight trials, like when Manhattan Beer Distributors sent four pallets of suds from their Oak Point outpost to Lower Manhattan in 2022 — or when UPS tested transporting containers on barges between Brooklyn and Bayonne, New Jersey, that same year.

There have also been fossil fuel-free shipments by “cargo sailboat” in the New York harbor in recent years — including delivery of chocolate and wine all the way from France, and routes traveling up the Hudson River.

EDC and DOT put out a separate call in November for ideas from the private sector on how to make better use of marine transportation.

Congestion pricing will also make trucking companies rethink how they move through the city, Taylor noted. Some may switch to overnight deliveries to benefit from the lower toll, but waterways could be another appealing alternative.

EDC plans to do an environmental review for the six piers later this year, and share more detailed plans by the end of 2024, before starting construction a year after that.

“The Adams Administration has made it clear that we need to get more trucks off our streets and reduce congestion to improve the quality of life for New Yorkers. The Blue Highways initiative is a game-changing opportunity to do just that, activating our waterfront freight operations in a way that hasn’t happened in generations,” said EDC spokesperson Adrien Lesser in a statement.