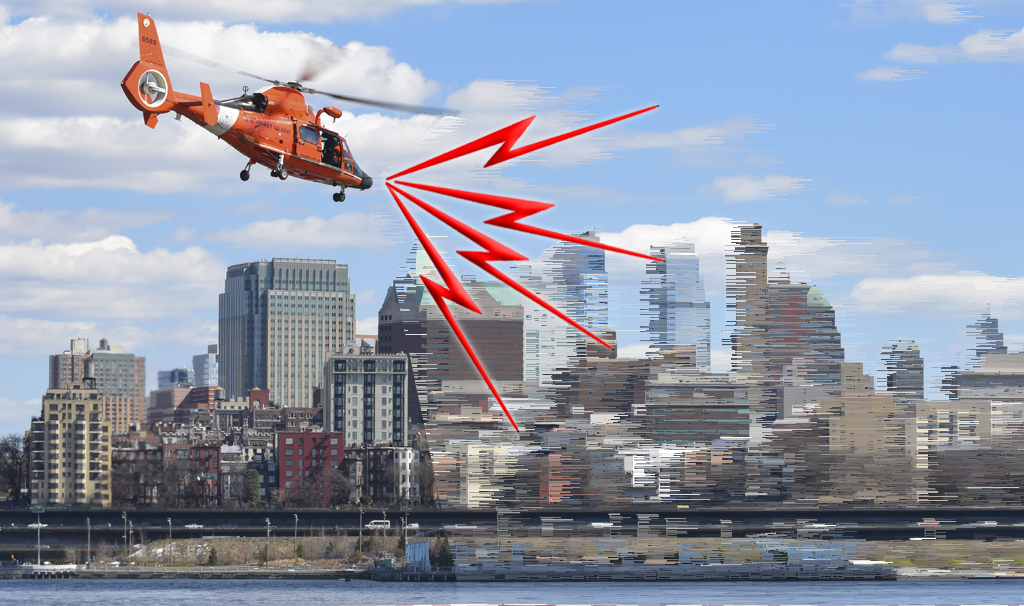

Editor’s note: On Tuesday, Streetsblog contributor Charles Komanoff testified in favor of two City Council bills to limit noise from helicopter flights over New York City. But those city bills — Intro 26 and Intro 70 — are opposed by the Adams administration and may not pass. If they don’t, there’s another way to reduce some of the aural assault, he argues in this op-ed.

Here’s a surefire way to curb helicopter noise over New York: tax it.

Not the noise, per se, but the flights that generate it.

State bills by Sen. Kirsten Gonzalez and Assembly Member Bobby Carroll (S7216B and A7638B) would sock a new $400 “noise tax” on “nonessential” flights departing or landing at the city’s heliports — a deserved fee that, like cigarette taxes, soda surcharges and alcohol excise fees before it, will dramatically reduce flights.

The concept is known as externality pricing. Nonessential sightseeing and “commuting” helicopter flights would be subject to the tax, but not medical, news-gathering or, sorry to say, NYPD flights.

The proposed Gonzalez-Carroll noise fee is $100 per occupied seat or $400 per flight, whichever amount is larger. As we’ll see in a moment, these levies fall considerably short of the average helicopter flight’s full societal cost. But they are a commendable starting point. The levies can be raised later on, as methodologies for quantifying helicopter noise costs mature — a process that will be aided by passing a related bill in the Council, Intro 27. The fees can also be lowered if quieter helicopters emerge — which the Gonzalez-Carroll bills will incentivize.

“Cost internalization” — another term for this kind of social-damage pricing — is long overdue for helicopter noise. “Luxury” helicopter flights — a more apt term, perhaps, than “nonessential” — are purely discretionary. Anyone taking a luxury helicopter flight — whether to the Hamptons or JFK or for sightseeing — has money to spare, as revealed by their pricey transportation choice. Taxing helicopter noise is, thus, entirely consistent with economic justice. Moreover, these flights impose other costs beyond noise, such as carbon pollution and particulate-exhaust pollution, on everyone around or below.

Consider Blade’s JFK service from the West 30th Street heliport in Manhattan. I’ve made a preliminary but serviceable calculation suggesting that one such flight lasting just seven minutes steals around $2,500 worth of peace and quiet from city residents.

This calculation draws on the following concepts and assumptions:

- Loud helicopter noise radiates audibly for a mile in all directions, creating an effective mile-wide “noise field.”

- Approximately one-quarter of Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens households live within a mile of the roughly 15-mile flight path from the Hudson River at 30th Street to JFK Airport, putting 625,000 households within the helicopter noise field.

- The average such household is subjected to the helicopter noise for 44 seconds — based on an assumed 7-minute flight duration which translates to an average speed of 129 mph (calculated as 15 miles times 60 minutes per hour divided by seven minutes).

- A 20-decibel increment in ambient noise levels within the noise field during exposure.

- A “Noise Depreciation Index” of 1 percent, denoting a 1-percent reduction in property values — a proxy for noise annoyance — for each 1 decibel increase in noise levels above customary neighborhood levels. (This “NDI” concept and value were established in my and Howard Shaw’s monograph, Drowning in Noise: Noise Costs of Jet Skis in the United States, published by the Noise Pollution Clearinghouse in 2000; pages 67-68.) (Note: the NDI is applied only during the 44 seconds in which the helicopter is audible.)

- Monthly rent of $1,200 per household, a “placeholder” assumption that can be firmed up in the future.

The collective per-flight noise annoyance is then 625,000 households times 20 percent (NDI of 1 percent times 20 excess decibels) times $1,200 monthly rent per household times 44 divided by 2,600,000 (seconds of noise exposure divided by seconds in a month). The calculation yields $2,538, which rounds to $2,500.

The Gonzalez-Carroll $400 noise fee offsets only some of that damage. But it amounts to a roughly 40-percent surcharge to Blade’s $250 standard ticket price to JFK — a fee that will bite. Assembly Member Carroll has been a legislative leader on externalities taxing, and it’s great to see Sen. Gonzalez also taking up the cause.

A noise fee raising the price of a commuter helicopter trip by 40 percent will cut usage, hence, the number of flights, by 30 to 50 percent, as some would-be passengers opt out. (Yes, just like congestion pricing, except more draconian, and deservedly so, given luxury helicopters’ societal uselessness.)

That will not only bring a healthy measure of peace and quiet, it will also generate $10 to $15 million per year — revenue that New York City (or State, if the legislation requires it) can use to expand and enforce noise-abatement rules citywide or statewide.

I computed a 30- to 50-percent drop-off by running the 40-percent price increase through two different price-elasticity values: negative 1, denoting fairly elastic demand; and negative 2, corresponding to very high price-responsiveness. (The calculations are: 1.40^(-1) which yields 0.71, indicating 29 percent of flights disappear; and 1.40^(-2) which yields 0.51, indicating 49 percent of flights disappear.) (The up-carrot sign is shorthand for exponentiation.)

I understand that a total of around 50,000 helicopter flights a year, or perhaps a tad more, take off or land each year at New York City's three heliports. Multiplying that figure by the $400 per-flight tax and then by the “survival” percentages of 70 percent and 50 percent yields my revenue range of $10 to $15 million a year.

(For the full presentation of these assumptions and calculations, download this Excel spreadsheet from my website.)

Where do we go from here? If it is true that the Council bills banning helicopter flights from the city heliports are non-starters with this city administration, the state bills from Gonzalez and Carroll are a worthy backstop, promising to do away with 30 to 50 percent of tourist and commuting helicopter flights. And while it’s true that New Jersey-based tourist helicopter flights wouldn’t be covered, New York’s noise tax would establish a template for advocates from both states to tackle New Jersey-based flights.

Why bother taming helicopter flights? Most viscerally, they’re pervasive nuisances, stealing equanimity from a million or more New Yorkers. (The annoyance costs are doubtless greater for sightseeing flights that circle and hover seemingly endlessly, not just for seven minutes.) They’re also wasteful, senseless indulgences that signify the vast damage from unfettered use of fossil fuels. If we can’t bring urban helicopter idiocy under social control, there isn’t much hope for stemming the climate crisis.

Conversely, imposing a social price on these flights could, like congestion pricing, function as a stepping-stone toward the ultimate climate policy tool: carbon taxing. Every means of implementing externality pricing brings a robust carbon price one step closer. Let’s get on with it.

(The Council bill endorsing the Gonzalez-Carroll noise tax legislation is Resolution 0085-2024.)