The city could save roughly 50 lives every year by simply getting the worst drivers off the road — but doing so is going to be a heavy lift at 1 Police Plaza, City Hall and in the state Capitol.

That's the topline finding of a new research paper by scholar Nicole Gelinas, who analyzed the more than 200 fatal crashes in 2022 to discover that 47 people's lives could have been saved if the worst of the worst drivers hadn't been allowed to get behind the wheel.

No one should feel sympathy for such recidivist perps, said Gelinas, the contributing editor at City Journal.

"Vehicles whose drivers accumulate five or more red-light and speed camera tickets a year are not New York’s 'average drivers,'" she wrote in the paper, released on Thursday. "They are disproportionately likely to be involved in a fatal crash (to say nothing of serious injuries and general menacing behavior on the road)."

Heightened enforcement or non-carceral punishment against those drivers should not be controversial, she added. "[It] would make New York City’s roads substantially safer without harming the average driver, who gets fewer than one speed or red-light camera ticket per year."

Some background

It's not as if Vision Zero has been a failure — far from it. As Gelinas points out, there were 701 fatalities from vehicle crashes in 1990 and there were 206 in 2018, a drop of 70 percent. But those numbers have ticked up again (to 262 last year), so she argues that the city must make better use of the massive trove of camera data it has at its fingertips to deaths declining again.

Referring back to Streetsblog's coverage of the killing of 3-month-old Apolline Mong-Guillemin, Gelinas sees it as a perfect example of the city failing, despite clear evidence of a ticking time bomb on the streets: The driver, Tyrik Mott, had racked up 92 school-zone speed camera violations and 15 red-light camera violations, and had been stopped several times by police, yet was always returned back to the street to drive recklessly again.

Speed cameras work — but they're only a tool. Violations at specific locations with cameras fell by 70 percent. And reviewing millions of lines of code from tickets issued in 2022, Gelinas found that once speed cameras were in use 24 hours a day, seven days a week, violations dropped 30 percent. Few drivers get a second ticket, choosing instead to change their reckless behavior rather than pay the $50 for it.

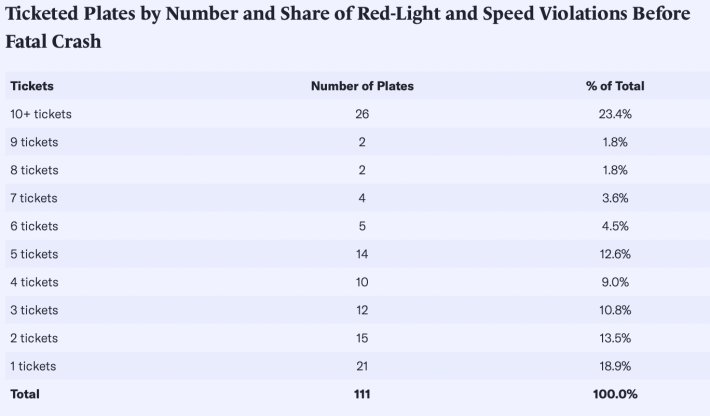

But a handful of drivers continue to drive recklessly, and that's where city and state officials make better use of the tool: During the first eight years of the speed camera program, 12 percent of vehicles garnered between five and nine tickets, and an additional 6 percent got 10 or more tickets.

And those drivers are the ones who are causing more crashes. In 2022, 63 percent of crashes involved at least one vehicle with at least one camera-issued ticket — and those vehicles had received, on average, seven tickets prior to the incident.

But that number is deceptive, too: 23 percent of vehicles in fatal crashes had received 10 or more tickets in the months preceding the crash and another 24 percent of vehicles in fatal had received between five and nine tickets.

Yet only 3 percent of all the ticketed vehicles got 10 or more camera-issued violations, and only 10 percent received between five and nine tickets. So the ones in fatal crashes are clearly disproportionate.

Removing those drivers from the road would have saved 47 lives in 2022, including 22 pedestrians and four cyclists, according to Gelinas's number crunch.

The fix ain't in

Fixing this problem isn't going to be easy, as Streetsblog and others have long discovered. It sounds so simple though: "New York’s policy goal should be to take vehicles ... that have accumulated five or more speed or red-light tickets within one year off the road," Gelinas writes. Beyond an education program to "deter drivers of such vehicles from accumulating five or more tickets in the first place," Gelinas recommends:

- Escalating fines after the first two tickets. This, of course, would require state legislation.

- The state Department of Motor Vehicles should revoke the registration on any vehicle that gets five red-light or speed tickets in 12 months. The city DOT has urged passage of an existing state bill to do just that, S451/A7621.

- Increased police enforcement: This is a bit of a non-starter for many road safety advocates because of how many police stops turn violent. In addition, the NYPD seems to have abandoned the idea of policing the road, with cops conducting 510,000 traffic stops in 2020 down from 985,000 in 2019. The post-pandemic number of stops is still down at least 30 percent from 2019.

- Find a market solution to dangerous driving by getting insurance companies to use ticket data to adjust their rates. New York Times editors apparently find this concept a violation of a reckless driver's privacy rights, though it definitely defends the rights of the rest of us to be safe from them. And, Gelinas said in an exchange with Streetsblog, "Insurance companies just don't want to go near it."

Most aggressively, Gelinas calls for the state to take over and revive the city's Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program, which was initially written to seize vehicles that racked up five red-light camera or 15 speed camera violations within 12 months, but was watered-down to allow (not require!) DOT to order such drivers to take a safety course.

The cars of drivers who skipped the course, or reoffended within six months could be seized. But even though there were tens of thousands of drivers who hit the threshold, in the end, only 885 drivers took the course, and hundreds of those reoffended, but only 12 vehicles were ever seized.

"The state could consider working with the local sheriff’s office — which regularly impounds vehicles for nonpayment of tickets without incident — to impound the vehicles that are in violation of a revamped dangerous vehicle abatement act," Gelinas writes. But here again, the specter of Tyrik Mott looms large: His car was subject to towing repeatedly for non-payment of tickets — but was never actually towed. It either couldn't be found or, perhaps, was parked off-street.

All of which leads back to the central frustration: solutions are at hand, but legislators and regulators don't seize them, often because they don't want to criminalize driving, which is so normalized in our society. The trick, Gelinas told Streetsblog, is to only normalize the normal drivers.

"Enforcement doesn't harm the ordinary driver, and it really does save lives," she said. "It could be your own kid's life. The saddest thing is seeing someone rack up 20 tickets in a few months, and then the tickets just abruptly stop, and the crash report shows that he basically slammed into a wall and killed himself.

"If you or your spouse or your kid is racking up five tickets, 10 tickets, 20 tickets, you are in the minority, you are behaving aberrantly and dangerously, and you will end up hurting yourself or someone else," she said.