Induced demand isn't just a theory — it's apparently a policy of the city Department of Transportation.

The agency recently added more rush hour car capacity to a Lower East Side road in a debunked attempt to ease congestion approaching the Williamsburg Bridge — the second time in as many months that the DOT has sought to reduce traffic by accommodating drivers rather than reducing their numbers. And locals who don't have cars are angry.

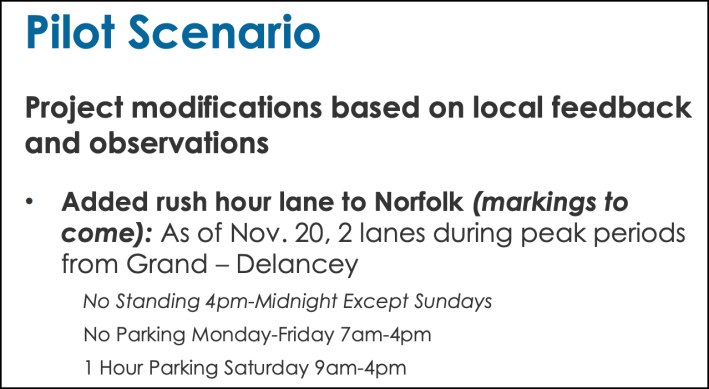

The DOT converted curbside parking space on Norfolk Street north of Grand Street into a second moving lane during rush hours as a "pilot" to divert traffic from congested Clinton Street and speed up travel times for the many motorists coming from the FDR Drive turning off Grand to get to the Williamsburg span.

The shift will incur 13 percent more cars, according to DOT's forecast, flying in the face the state's finally approved congestion pricing toll to enter downtown Manhattan that aims to cut car trips by 15–20 percent, but officials at the city agency — which controls the Big Apple's streetscape — painted the area's heavy traffic as too big a challenge to solve.

“There is a lot of traffic and it’s going to move around, we’re not going to make it evaporate, unfortunately,” DOT’s Carl Sundstrom told Community Board 3’s Transportation Committee at an update presentation [PDF] about the project last Tuesday night.

"It’ll be interesting to see what happens with congestion pricing and if that reduces the traffic volume, and we’ll see," Sundstrom added. "But right now, yes, we are essentially moving the traffic a little bit on a certain blocks, but that’s because we want to improve the traffic flow and we’re working to improve the safety at the intersections."

Residents were dismayed that the city wasn't doing more to deter motorists from using their neighborhood as a short cut, saying officials were too obsessed with driver convenience.

"The real challenge here is that we’re just moving pieces around on a board without removing some of the pieces,” said resident Michelle Kuppersmith, who is also is a member of Community Board 3, but said she was speaking on her own behalf.

"I don’t want us to be prioritizing flow over safety which I fear is where we’re at right now," added Kuppersmith. "I want it to be so onerous for cars to drive through our neighborhood that they stop doing it."

The agency's presentation to the transportation committee came on the eve of state transit officials green-lighting the $15 charge to enter Manhattan below 60th Street — including via the currently free Williamsburg Bridge.

Traffic planners have established for decades that creating more road infrastructure encourages more drivers to use it, a principle known as induced demand.

DOT followed a similarly flawed logic of peddling to motorists by proposing in late October to give extra space to drivers on a bottleneck near Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn, rather than reducing car infrastructure in the transit-rich part of the borough.

The Manhattan road redesign previously drew criticism from the community board when officials first pitched it early last year, when they proposed to simply expand Norfolk to two lanes, before dialing their plans back a bit to just more traffic space during peak traffic periods, according to the presentation Tuesday.

DOT previously forecast that their proposal would draw more total traffic to the corridors, with its numbers [PDF] predicting an increase in combined daily traffic on Norfolk and Clinton Streets from 1,130 to 1,280 vehicles, up 13 percent, but officials argued that it would also shave off one-and-a-half minutes of travel time for motorists with better flow on Grand Street.

"Because this plan is more efficient in moving traffic, more traffic will be drawn to the route. It’s still expected that Norfolk will be able to handle all this vehicle traffic once it’s up to two lanes,” Sundstrom said at the time.

DOT spokesman Vin Barone disputed that the city was adding more car space, claiming the higher numbers were "from other streets, not more cars total."

"The idea that DOT is adding vehicle capacity in this area of the Lower East Side is fundamentally incorrect," said Barone in a statement. "DOT is working to balance existing traffic flows between Clinton and Norfolk to reduce cut-through traffic in the neighborhood and help improve pedestrian and cyclist safety."

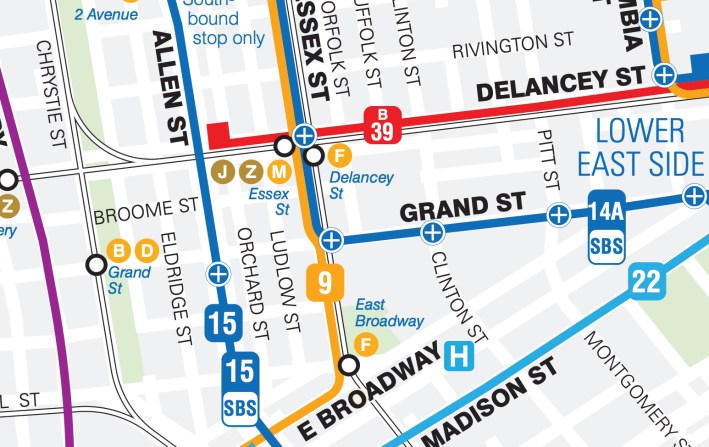

The downtown area is blessed with six subway lines and even more bus routes, and more than eight in 10 households in CB3 don't own a car, according to Census data crunched by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Transportation Alternatives.

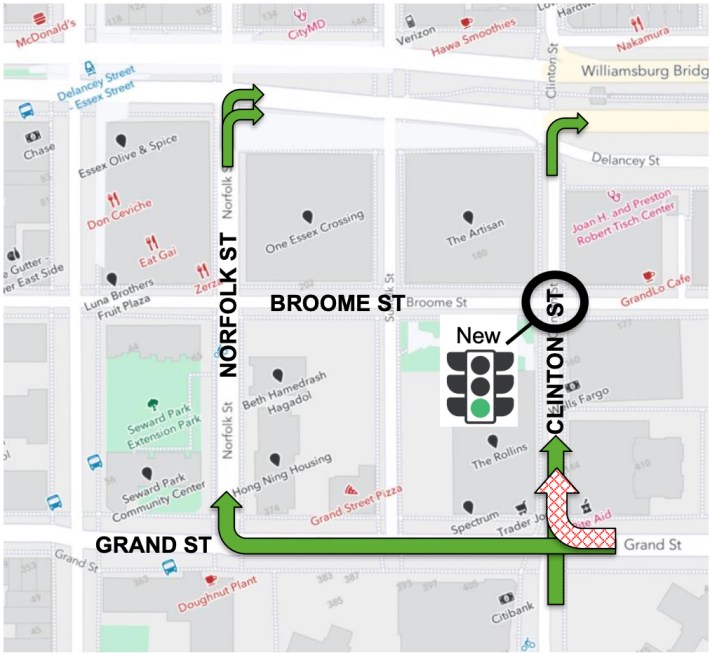

The city's revamp now bans turns from Grand Street onto Clinton Street, and DOT converted the former right-turning lane into a row of parking with a painted pedestrian island at the intersection. Street planners also moved the formerly-unprotected bike lane from the middle of Grand Street to the curb, so cyclists have the row of parking between them and moving traffic.

Drivers are supposed to turn off Grand at Norfolk Street instead, and there's also no marked crosswalk across Delancey Street at Norfolk, so there's fewer conflicts between pedestrians and turning drivers under the redesign, the agency argued.

The overhauls additionally include a new traffic light at Clinton and Broome Streets, while also giving motorists more green time at Norfolk and Delancey Streets.

The redesign at Clinton is an improvement, with better separation from traffic for pedestrians and cyclists, but motorists continue to illegally turn on that street, even with traffic agents there, a recent video by Kuppersmith shows.

“The enforcement is bupkis,” said the Lower East Sider, using the local argot. “The hope was it would reduce conflicts between pedestrians and conflicts, but without real and aggressive enforcement both from passive and active sources, drivers will continue to flout the law.”

Another board member at the meeting told city officials they essentially just moved the area's traffic problem up a few blocks.

“The original goal was, going 10 years back, coming to these meetings, is to stop the traffic from piling up from Clinton back towards the FDR, which I don’t think this has solved, it just pushed it a couple of blocks down,” said Daniel Tainow.

DOT officials said the trial redesign went into full effect last month and will last a year, when the agency plans to report back to the community board.