When it comes to flooding in Brooklyn, city officials always reprise the borough's famous catch phrase: Wait 'til next year.

The latest plan for fixing the notorious flood zone on Fourth Avenue won't be finished until 2033. That's 111 years and at least 17 mayoral administrations after the earliest documented flooding on the roadway that forms the border between Park Slope and Gowanus — and more than a decade after the city's most recent promise of a fix for the corridor's routine inundations.

Increasingly, the routine is what happened on the low-lying avenue during last Friday’s downpour from Tropical Storm Ophelia: waters rising high enough to lift parked cars, an open manhole turning into a mucky vortex, and a worker wading chest-deep through a construction site.

Residents and business owners laughed in disbelief at the city’s decade-spanning timeline to build out better drainage infrastructure in well-known trouble spots.

“By that time we would have lost our minds already,” said Alejandra Palma, one of the owners of Root Hill Cafe at Fourth Avenue and Carroll Street.

That intersection has repeatedly been at the receiving end of some of the worst of the floods in recent years — 10 times over the last eight years, according to Palma.

“It’s not our first rodeo,” she said, as she and her staff still worked on the cleanup from last Friday's deluge. “It’s just getting to a point where we don’t have the patience that the city has. It’s like, we’re done.”

Old problem, new solution?

Fourth Avenue has been flooding for as long as anyone can remember, but the rising waters have become worse and more frequent in recent years amid climate change. The avenue sits at the bottom of the hill of Park Slope, so a lot of rainwater pools on the thoroughfare during storms.

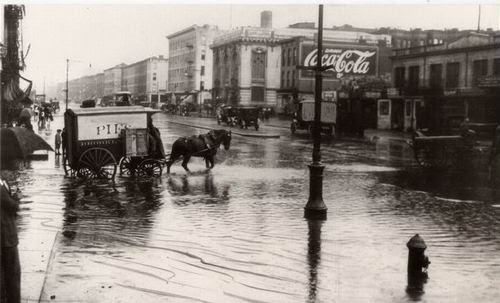

Root Hill Cafe owners alerted the city to the flooding in 2006, but it was hardly a new issue even then, as seen in this picture courtesy of the former Gowanus Lounge blog, reportedly taken in 1922 and showing a flooded Fourth Avenue at the same exact intersection in the age of horse-drawn carriages (note the building just to the left of the Coca-Cola sign — that's an old bathhouse that remains at the corner of President Street, albeit now as a gym).

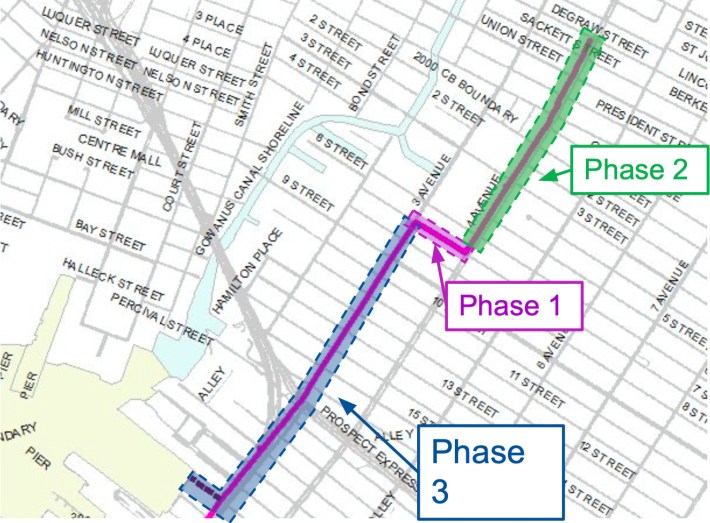

The Department of Environmental Protection last week presented a $233 million project at a community meeting on the eve of Ophelia last Thursday, saying the agency will reduce flooding in and around the corridor by building bigger sewer pipes over the coming decade in three phases.

The agency began planning for the new work when the city passed the Gowanus rezoning in 2021, and the first section of the work already started on Seventh Street, between Third and Fourth avenues, where new pipes will be done next year.

Next up are 12 blocks of Fourth Avenue stretching north of Seventh Street to Degraw Street, to be done by 2031. After that, the city will upgrade Third Avenue 15 blocks south of Seventh Street wrapping up by 2033.

DEP says Phase 1 of the project will reduce flooding by 40 percent on Carroll and Fourth. Phase 2 will eliminate 50 percent of the flooding and Phase 3 will get the neighborhood to 100 percent, explained DEP’s director of public design outreach Alicia West during the meeting last Thursday the Gowanus Oversight Task Force, a watchdog group focused on the city's commitments from the two-year-old rezoning.

The project will also benefit the larger neighborhood, with a flood reduction of up to 83 percent in the drainage area near the Gowanus Canal, and 19 percent less flooding in the tributary area that stretches as far as Prospect Park, according to DEP's presentation.

But the agency’s models still rely on a model for so-called five-year storms that drop up to 1.75 inches of rain an hour, officials admitted. That’s less than the roughly 2 inches an hour during Ophelia and well below the record-shattering 3.15 inches Hurricane Ida dropped in 2021.

Subterranean blues

The city's newer sewers built after 1970 can handle up to 1.75 inches an hour, but most of the Big Apple’s ancient subterranean system is older and fills up quicker, according to a June report by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

There's only so much room in the ground to expand sewers below Fourth Avenue, which also carries a subway line and utilities, according to officials.

West said the agency was doing a “multifaceted approach” for the neighborhood that also includes expanded rules requiring new developments include ways to retain stormwater, such as green roofs or tanks.

“All of that working together is going to work towards solving the problem,” the DEP official said.

Even if the city could build out larger pipes capable of taking up to 4 inches of rain an hour, they would also need to expand larger so-called "trunk sewers" which collect the water from the pipes and route it to treatment plans, DEP Commissioner Rohit Aggarwala told the City Council during an oversight hearing last year.

The city would have to raze buildings to widen the road enough for such large trunks, the DEP chief said at the time.

One longtime Fourth Avenue resident worried that the incoming work wouldn't really fix the street’s problems any time soon, citing a previous local sewer project that faced years of delays.

“I don’t expect this to be done — if ever — for 20 years or more, and I don’t believe it will ever alleviate the flooding,” said Joann Amitrano, an artist who owns Root Hill Cafe’s building and whose family has lived there since the early 1900s. "When the city has no money, and this is a major job, it’s very easy for this to disappear."

Amitrano was also concerned about the toxins flowing over from the neighborhood's heavily polluted land, including a brownfield site right across the street from her building.

Past delays

DEP and the Department of Design and Construction wrapped construction on a $54-million project to install “high level storm sewers” in Gowanus last July — a long-delayed project that was launched in the early 2010s.

That project covered Third Avenue and its side streets between Carroll and State streets, but focused more on diverting sewage from flushing into waterways when the city’s combined sewers carrying waste and rain runoff get overwhelmed during big storms.

That work reduced flooding by about 10 percent at Fourth and Carroll, according to West of DEP, but Palma of Root Hill Cafe said the inundation was actually worse this year than during Ida, with water rushing in faster leaving her and her patrons less time to evacuate.

“We see the drain [in the street], once we see it bubbling, it usually gives us about 10 minutes to get people out,” she said. “This time we had two to three minutes, tops.”

The city has also been slow to spend some $15 billion in federal recovery funds after Superstorm Sandy, Comptroller Brad Lander’s office found last year, with more than a quarter of that money still unspent a decade since that catastrophic weather event in 2012.

The city’s fiscal watchdog on Thursday announced a new probe into Mayor Adams’s handling of extreme weather in light of Hizzoner’s slow response to Ophelia last week, and Lander said he will also want to look at speeding up longer-term upgrades.

“Climate is moving much faster than our infrastructure, but we've got to push ourselves to be as responsive as we can, understanding that infrastructure projects take years, but that if you don't keep strong and aggressive action on them, they take decades,” Lander told Streetsblog during a virtual press conference.

Much of the Gowanus neighborhood is paved over a former salt marsh with a web of tidal creeks, making it difficult to really get rid of the flooding, said Andrea Parker, the executive director of the Gowanus Canal Conservancy, who said the city should help businesses adapt and recover after floods.

“We’re just going to be wet and I think that is a conversation we’ve not really had in the neighborhood in a way that we really have to,” said Parker.