The city’s permanent redesign of the former W. 22nd Street open street has transformed the once car-light corridor into a busy street where drivers refuse to share the road, but the one-block stretch does have some new spaces for people that used to be reserved for private vehicle storage.

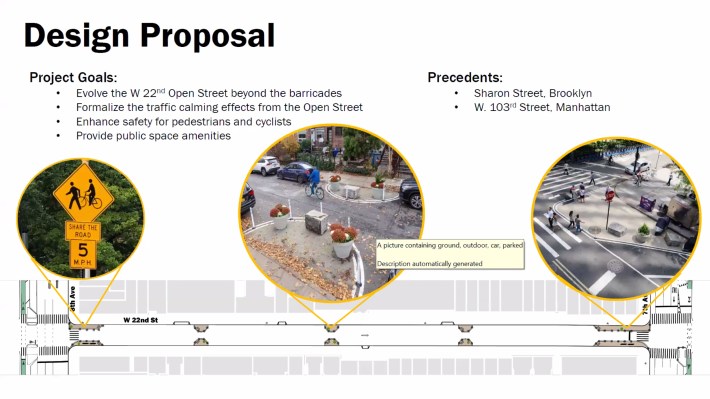

The Department of Transportation recently finished converting the block between Seventh and Eighth avenues into a road where drivers are supposed to go five miles per hour, thanks to neckdowns and daylighted corners to discourage speeding.

The changes add some nice public benefits to the Chelsea block, but residents lamented the loss of a true oasis from the automobile, where residents were able to stroll, parents could teach their kids to ride bikes without having to worry about cars.

“That was great. I would rather have a street closed [to cars],” said Inga Davidsson, a resident of 12 years.

She said she no longer feels safe walking in the roadway now, as she did before.

“No, of course not, people drive like maniacs,” said Davidsson. “It is back to normal.”

That “normal” was suspended for several years when residents organized to turn the block into a limited-access open street, meaning motorists could still enter the block, but only after moving metal barriers at the entrance.

Those gates also became a point of contention, with drivers hurling abuse at volunteers. And some neighbors were so upset by the inconvenience that they rallied to revert the street to full traffic late last year just as the city planned a longer-term revamp.

DOT and volunteers involved in the open street wanted to move beyond relying on barriers, and the new setup uses road design elements in the hopes of creating a shared environment for drivers, pedestrians, and cyclists.

Transportation workers painted beige extensions of the curb at the corners, and added flex posts, granite blocks, flower pots, and bike racks to keep them clear of drivers, a design DOT first presented to Community Board 4 back in June.

A sign at the entrance tells motorists to “share the road” with cyclists and pedestrians at five miles an hour, but motorists frequently ignore both those instructions.

The bulb-outs do make for shorter pedestrian crossings, and the vehicles turning from Eighth Avenue were going slower, but those driving straight from W. 22nd across the avenue tended to maintain the same speed as before.

To narrow the roadway along the block, DOT also installed five painted curbside semicircles with flower pots and flex posts, which make the roadway slightly tighter than the row of parked cars. Drivers largely whizzed through those without diminishing their speed.

“I don’t see how it slows things down,” said resident Craig Hanauer, as he walked his dog.

Hanauer, too, thought the previous setup was more effective, but added that the barriers were a hassle.

“I would prefer the prior, if it wasn’t such a battle to keep the gate closed,” he said.

The new curbside carveouts are definitely an improvement for the general public over what was in their place before — personal car storage.

DOT has been transitioning other open streets around the city into permanent makeovers this year. Most notably is the “gold standard” transformation of 34th Avenue in Queens into a 1.3-mile, largely car-free thoroughfare, thanks to full "plaza blocks" that divert cars and prevent through traffic entirely.

Others are slated bike boulevards, such as Berry Street and Underhill Avenue in Brooklyn — though the latter might be in doubt amid apparently yet another flip flop on street safety by Mayor Adams.

Some shorter sections have become permanent car-free plazas, such as sections of Broadway, Quisqueya Plaza in Inwood, and Banker’s Anchor in Greenpoint.

One advocate who originally petitioned DOT to install the W. 22nd open street back in 2020 — and helped push for DOT’s longer-term follow-up design — was optimistic, but said there would have to be more concrete data collection to measure the impact of the changes.

“This is a very flexible model that people can use to reimagine their street as public space,” said Melodie Bryant. “Showing them it can be used for something else besides parking and speeding is a really great model.”

Even if drivers were not following the posted speed limit, they were likely slowing down, said Bryant.

“Car drivers may not be going five miles per hour, but they’re not going 30 either, or 25,” she said. “They see that the streets are a little different.”

The block also got nine fresh bike racks for bikes, a key upgrade in a city that lacks good places to lock up bicycles.

“You used to have to wait eight years for a bike rack on the street,” she said.

She said that the street developed into a popular bike route during the pandemic, despite a lack of bike lanes, and has remained popular for cyclists.

Bryant’s positive response found common ground with a vocal neighbor who had been one of the organizers of the opposition to the revamp.

“It is certainly a vast improvement over the closure of the street that was in effect during the pandemic,” said Joe Neuhaus, a lawyer who lives one block over.

Neuhaus and his fellow opponents had previously criticized DOT for restricting traffic on this specific block, saying there was no park, school, or playground to attract people to it.

Now, the main change was that the city swapped out some parking spots for plantings and blocks, the attorney said.

“The planters and the like have a mild effect at beautifying the street at the cost of some parking spaces. I don’t think they’re likely to have much effect on traffic flow,” Neuhaus said. “The [five-mile-per-hour] speed limit’s of no consequence, no one’s going to obey that, there’s no particular reason why you would do that on that particular block — it just doesn’t make any sense.”

A DOT spokesperson declined to say whether the agency would install any extra infrastructure to slow down drivers, such as a speed bump, but the rep urged drivers to follow the law.

“We want drivers to follow the posted speed and adjust to the new granite and planter treatments that were installed,” said Scott Gastel.